Plot Summary

Supper with the Peacock

Bud and Olla invite Bud's coworker and his wife, Fran, to their rural home for supper. The evening is marked by the presence of a loud, beautiful peacock and Olla's display of her old, crooked teeth—a symbol of gratitude to Bud for helping her change her life. The couple's baby is strikingly ugly, but Olla and Bud's acceptance of him, and the peacock's odd place in the family, create a sense of strange, resilient love. Fran is both fascinated and unsettled, and the evening lingers in her memory as a turning point. The visit exposes the guests to a different kind of domesticity, one that is awkward, honest, and marked by small, unforgettable moments.

Second Chances, Old Houses

Wes, a recovering alcoholic, persuades his estranged wife, Edna, to join him in a rented house by the ocean, hoping to rekindle their marriage. The house, owned by Chef, becomes a fragile sanctuary where they attempt to rebuild trust and routine. Their children are distant, living their own lives. When Chef reclaims the house for his daughter, Wes and Edna are forced to confront the impermanence of their happiness. The loss of the house is a metaphor for the limits of second chances; they realize they cannot escape who they are, but they cherish the brief peace they found together.

The Sofa and the Fridge

Sandy's husband, after losing his job, becomes immobilized on the sofa, unable to reengage with life. His days blur into television, coffee, and reading the same pages of a book. When their refrigerator breaks, the couple is forced to act, searching the classifieds for a replacement and planning to attend an auction. The crisis with the fridge becomes a catalyst, stirring memories of Sandy's father and her own childhood. The story captures the quiet despair and small hopes of a couple struggling to preserve normalcy amid economic and emotional stagnation.

Estranged on the Train

Myers, traveling by train to Strasbourg to see his son after eight years of silence, is haunted by memories of their violent parting and the collapse of his marriage. On the journey, his gift for his son is stolen, and he is consumed by suspicion and regret. As the train nears its destination, Myers realizes he no longer wants to see his son, feeling only bitterness and alienation. The train's shifting cars and unfamiliar faces mirror his dislocation. Ultimately, Myers is swept along, uncertain of his direction, a stranger to his own family and himself.

A Small Good Thing

Ann and Howard order a birthday cake for their son, Scotty, who is struck by a car and lapses into a coma. As they endure the agony of waiting in the hospital, they are harassed by mysterious phone calls from the baker about the unclaimed cake. When Scotty dies, the couple, raw with grief, confront the baker, who is oblivious to their tragedy. In a moment of epiphany, the baker offers them warm bread and coffee, and they find a measure of comfort in the simple act of eating together. The story is a meditation on loss, misunderstanding, and the healing power of small gestures.

Selling Vitamins, Losing Friends

Patti, seeking self-respect, becomes a vitamin saleswoman, quickly rising to manage a team of women. The work is grueling and unstable; girls come and go, and the business falters. Personal boundaries blur—Sheila, a team member, confesses her love for Patti, and the narrator, Patti's husband, is drawn to another woman, Donna. After a chaotic party and a disturbing night at a bar, relationships unravel. The vitamin business becomes a metaphor for the characters' search for meaning and connection, and their dreams dissolve into exhaustion and resignation.

Champagne and Careful Living

Lloyd, separated from his wife Inez, lives alone in a cramped apartment, drinking champagne and eating doughnuts for breakfast. When Inez visits, Lloyd is tormented by a blocked ear, a minor crisis that becomes symbolic of his inability to listen and connect. Inez helps him, and they share a moment of intimacy and care, but the visit is fleeting. Lloyd is left to his routines and anxieties, haunted by the fear of losing even the small comforts he has. The story explores the fragility of self-sufficiency and the longing for companionship.

Drying Out at Frank Martin's

At Frank Martin's drying-out facility, the narrator and J.P., a chimney sweep, share their stories of addiction and loss. J.P. recounts falling into a well as a child and later falling in love with Roxy, a fellow sweep. Their marriage is battered by his drinking, leading to violence and estrangement. The narrator, also struggling with relationships, finds solace in J.P.'s company. The facility is filled with men on the edge, each with their own story. Through shared pain and small rituals—meals, conversations, a New Year's cake—the men find a tenuous sense of community and the possibility of change.

The Gun and the Waiting Room

Miss Dent, after holding a gun on a man who wronged her, waits in a deserted train station, haunted by the encounter. She is joined by an odd couple, an old man and a woman, whose bickering and self-absorption contrast with her silent turmoil. Their conversation is filled with grievances and regrets, and they project their anxieties onto Miss Dent. When the train arrives, the three board together, observed by indifferent passengers. The story captures the loneliness and unpredictability of lives intersecting in the night, each carrying their own burdens.

Fever and Letting Go

Carlyle, abandoned by his wife Eileen, struggles to care for his children and find a reliable sitter. After a series of failures, Mrs. Webster, an elderly woman, brings stability to the household. When Carlyle falls ill with a fever, Mrs. Webster tends to him, and Eileen calls with cryptic advice about recording his experience. As Mrs. Webster prepares to leave for a new life, Carlyle is forced to confront the end of his marriage and the necessity of moving on. Through illness and conversation, he finds a measure of peace, accepting the past and the uncertainty of the future.

Displaced in the Desert

The Holits family, dispossessed farmers from Minnesota, arrive at an Arizona apartment complex, carrying their few possessions and a horse's bridle. The manager, Marge, observes their struggles to adapt—Betty, the stepmother, works as a waitress; the boys swim; Holits drifts. The bridle, left behind when they move on, becomes a symbol of lost control and direction. The story is told through the eyes of neighbors, capturing the quiet desperation and fleeting connections of people on the margins, always moving, always hoping for a new start.

The Blind Man Arrives

The narrator's wife invites her blind friend, Robert, to stay with them after the death of his wife. The narrator is uneasy, harboring prejudices and jealousy over their close friendship. Over dinner and drinks, the blind man's warmth and humor begin to break down the narrator's defenses. The evening unfolds with awkwardness, laughter, and unexpected camaraderie. The blind man's presence exposes the narrator's emotional blindness and his inability to communicate with his wife. The visit becomes a catalyst for self-reflection and change.

Drawing the Cathedral

Late at night, the narrator and the blind man watch a documentary about cathedrals. The narrator struggles to describe the grandeur and meaning of these buildings, realizing his own inability to see beyond the surface. The blind man suggests they draw a cathedral together, guiding the narrator's hand as they create the image on paper. With his eyes closed, the narrator experiences a moment of epiphany, feeling both liberated and grounded. The act of drawing becomes a metaphor for empathy, understanding, and the possibility of transformation.

Characters

The Narrator (Various Stories)

Carver's narrators are often working-class men, emotionally stunted and struggling with communication, addiction, or loss. They are husbands, fathers, or friends, caught in the inertia of daily life. Their relationships are marked by misunderstanding and longing, and they often find themselves on the periphery of their own lives. Through small crises—a dinner, a broken fridge, a visit from a blind man—they are forced to confront their limitations and, occasionally, glimpse moments of epiphany or connection. Their development is subtle, marked by fleeting insights rather than dramatic change.

Fran

Fran, from "Feathers," is the narrator's wife, tall and striking, with a practical outlook and a deep ambivalence about domestic life. She is wary of new experiences and skeptical of others, yet she is also capable of tenderness and curiosity. Her relationship with her husband is intimate but strained, shaped by shared routines and unspoken desires. The evening at Bud and Olla's house becomes a touchstone for her, a moment that lingers as both a possibility and a warning.

Bud and Olla

Bud and Olla are a rural couple whose home is filled with oddities—a peacock, a mold of Olla's old teeth, an unusually ugly baby. Bud is practical and good-natured, while Olla is shy, grateful, and marked by past hardship. Their relationship is built on acceptance and small acts of care. They embody a kind of survivalist love, making do with what they have and finding beauty in the strange and imperfect.

Wes and Edna

Wes, a recovering alcoholic, and Edna, his estranged wife, are drawn together by the hope of starting over. Wes is vulnerable, remorseful, and desperate for redemption; Edna is cautious, torn between loyalty and self-preservation. Their relationship is shaped by shared history and the weight of their failures. The loss of their temporary home forces them to confront the limits of change and the inevitability of loss.

Ann and Howard Weiss

In "A Small, Good Thing," Ann and Howard are a middle-class couple whose son's accident and death shatter their sense of security. Ann is nurturing, anxious, and desperate for answers; Howard is rational, supportive, but ultimately helpless. Their grief isolates them but also brings them together in vulnerability. Their encounter with the baker becomes a moment of epiphany, allowing them to begin healing.

The Blind Man (Robert)

Robert, the blind man in "Cathedral," is open, humorous, and unselfconscious. His blindness is not a limitation but a source of insight, allowing him to connect deeply with others. He challenges the narrator's assumptions and facilitates a moment of epiphany through the act of drawing together. Robert's presence exposes the emotional blindness of those around him and becomes a catalyst for empathy and change.

Patti

Patti, the vitamin saleswoman, is driven by a need for self-respect and achievement. She is resourceful and supportive, but the pressures of her job and the instability of her team wear her down. Her relationships—with her husband, her employees, and her friends—are marked by blurred boundaries and unmet needs. Patti's dreams are eroded by exhaustion, but she persists, searching for meaning in small victories.

Lloyd

Lloyd, from "Careful," is a man adrift after separating from his wife. He is meticulous, cautious, and obsessed with minor details—his ear, his breakfast, his drinking. Lloyd's interactions with Inez reveal his longing for connection and his inability to change. His carefulness is both a defense and a prison, trapping him in a cycle of worry and avoidance.

Carlyle

Carlyle, a high school teacher, is left to care for his children after his wife leaves. He is overwhelmed by responsibility and haunted by the past. His attempts to find help are met with disappointment until Mrs. Webster brings stability. Carlyle's illness and conversations with Mrs. Webster and his ex-wife force him to confront his grief and accept the end of his marriage. He emerges with a sense of acceptance and the possibility of moving forward.

Betty Holits

Betty, the stepmother in "The Bridle," is uprooted from her life in Minnesota and struggles to adapt to a new environment. She works hard, cares for her stepsons, and endures her husband's decline. Betty's vulnerability is revealed in her conversations with Marge, the apartment manager, and in her final act of leaving the bridle behind. She embodies the quiet strength and sorrow of those who are always starting over.

Plot Devices

Ordinary Objects as Symbols

Carver uses mundane objects—a peacock, a loaf of bread, a broken fridge, a bridle, a birthday cake, a cathedral drawing—as focal points for his characters' emotions and relationships. These objects become symbols of longing, loss, hope, and connection. Their presence grounds the stories in reality while opening up layers of meaning, allowing small moments to resonate with significance.

Minimalist Narrative Structure

Carver's stories are marked by brevity, understatement, and a focus on dialogue and gesture. He eschews elaborate exposition, instead revealing character and conflict through what is left unsaid. The narrative often begins in medias res, with little background, and ends without clear resolution. This structure mirrors the uncertainty and ambiguity of real life, inviting readers to fill in the gaps.

Foreshadowing and Recurrence

Carver plants subtle clues—an offhand wish, a remembered evening, a recurring phone call—that foreshadow later events or emotional shifts. Characters' memories and regrets recur, shaping their present actions and relationships. The repetition of small details—meals, drinks, gestures—creates a sense of rhythm and inevitability, underscoring the persistence of longing and the difficulty of change.

Moments of Epiphany

Many stories culminate in a moment of revelation—a wish made at dinner, a conversation with a stranger, the act of drawing a cathedral. These epiphanies are often quiet, internal, and ambiguous, but they mark a shift in the characters' understanding of themselves and others. The stories suggest that transformation is possible, but rarely dramatic or complete.

Analysis

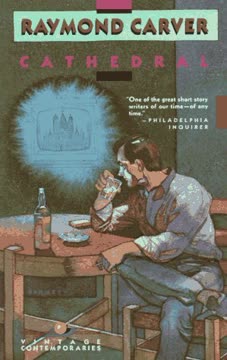

Raymond Carver's "Cathedral" and its companion stories distill the struggles and yearnings of ordinary people into moments of startling clarity and emotional resonance. Through minimalist narrative structure and a focus on the mundane, Carver reveals the profound within the everyday: the ache of loss, the hunger for connection, the small mercies that sustain us. His characters are often isolated, wounded by failed relationships, addiction, or economic hardship, yet they persist, seeking meaning in small gestures and fleeting encounters. The stories explore the limits of communication—how words fail, how silence speaks, how empathy can bridge the gap between self and other. The titular story, "Cathedral," encapsulates Carver's vision: a blind man leads a sighted narrator to a new way of seeing, not through explanation, but through shared creation. In a world marked by disappointment and uncertainty, Carver suggests that grace is found not in grand gestures, but in the willingness to reach out, to listen, and to draw together—however imperfectly—the shape of hope.

Last updated:

Review Summary

Cathedral is a highly regarded short story collection by Raymond Carver. Readers praise Carver's minimalist style, authentic portrayal of working-class Americans, and ability to evoke deep emotions through simple prose. The stories often focus on ordinary people facing personal struggles, with themes of alcoholism, failed relationships, and existential crises. While some critics find the stories bleak, others appreciate the moments of humor and redemption. The title story "Cathedral" is frequently cited as a standout, exploring themes of connection and understanding.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.