Key Takeaways

1. Ethical Leadership is Essential in Today's Complex Education

Each administrative decision carries with it a restructuring of human life: that is why administration at its heart is the resolution of moral dilemmas.

Profound impact. Every decision made by an educational leader, from curriculum choices to disciplinary actions, fundamentally reshapes the lives of students and the broader community. In an era marked by terrorism, wars, financial instability, and rapid technological advancement, these decisions are more complex and carry greater weight than ever before. Ethical leadership is not merely a desirable trait but a critical necessity for navigating these turbulent times.

Navigating complexity. Modern society is characterized by increasing demographic diversity, presenting both opportunities and challenges for schools. Educational leaders must foster tolerant and democratic environments that recognize and appreciate differences across various dimensions, including:

- Race and ethnicity

- Religion and social class

- Gender, disability, and sexual orientation

This requires a deep understanding of ethical principles to ensure equitable and just outcomes for all.

Beyond compliance. While legal and policy frameworks provide some guidance, they often fall short in addressing the nuanced moral dilemmas faced daily. Ethical leadership goes beyond mere compliance, demanding that leaders actively reflect on their values, anticipate consequences, and make decisions that genuinely serve the well-being of all individuals within the educational ecosystem. This proactive ethical stance is vital for building trust and maintaining the integrity of the educational system.

2. Beyond Traditional: Four Paradigms for Ethical Decision-Making

Throughout this book, the reader is asked to consider current and challenging real-life ethical dilemmas using four paradigms.

Multidimensional approach. To effectively address the intricate moral dilemmas in education, a single ethical viewpoint is insufficient. This book introduces a comprehensive framework that encourages leaders to analyze situations through multiple lenses, moving beyond simplistic notions of right and wrong. This multidimensional approach provides a richer, more complete understanding of complex issues.

Expanding the toolkit. Traditionally, ethical discussions in education often centered on principles of justice. However, this framework expands the toolkit by integrating three additional, complementary paradigms: the ethic of care, the ethic of critique, and the ethic of the profession. By consciously applying these diverse perspectives, educational leaders can uncover hidden assumptions, identify overlooked stakeholders, and formulate more holistic and equitable solutions.

Holistic understanding. The goal is not to favor one paradigm over another, but to encourage a kaleidoscopic view of ethical problems. This practice helps leaders recognize their own inherent biases or preferred approaches, prompting them to consider alternative viewpoints. By doing so, they can develop a more nuanced understanding of the ethical landscape and make wiser, more informed decisions that account for the full spectrum of human experience and societal impact.

3. The Ethic of Justice: Upholding Rights, Laws, and Fairness

For Kohlberg, “justice is not a rule or set of rules, it is a moral principle . . . a mode of choosing that is universal, a rule of choosing that we want all people to adopt always in all situations” (p. 39).

Foundational principle. The ethic of justice is rooted in the liberal democratic tradition, emphasizing rights, laws, and fair treatment for all individuals. It posits that decisions should be guided by universal principles, ensuring that people who are similar in relevant respects receive similar treatment. This perspective often involves examining existing policies, legal precedents, and the concept of equal opportunity.

Rules and impartiality. This paradigm encourages leaders to ask:

- Is there a law or policy that applies to this situation?

- Should it be enforced, and is its application fair?

- Are individual rights being protected?

- Does the decision uphold principles of equity and equality?

It seeks impartiality, ensuring that personal biases do not sway decisions, and that the greater good of the community is considered within a framework of established rules.

Limitations and overlaps. While crucial for maintaining order and protecting fundamental freedoms, a sole reliance on justice can sometimes overlook the nuances of human relationships or systemic inequities. The book highlights that justice may overlap with other paradigms, especially when laws are deemed unjust (e.g., historical segregation laws) or when their application leads to unintended harm, prompting a need for deeper ethical inquiry.

4. The Ethic of Care: Prioritizing Relationships, Empathy, and Well-being

To Noddings, and to a number of other ethicists and educators who advocate the use of the ethic of care, students are at the center of the educational process and need to be nurtured and encouraged, a concept that likely goes against the grain of those attempting to make “achievement” the top priority.

Relational focus. In contrast to the abstract impartiality of justice, the ethic of care emphasizes relationships, empathy, and responsiveness to the needs of others. It places students at the heart of the educational process, advocating for nurturing environments where individuals feel seen, heard, and valued. This paradigm challenges traditional, often patriarchal, models of leadership that prioritize efficiency or strict adherence to rules over human connection.

Compassion and consequences. Leaders applying the ethic of care consider the emotional and relational impact of their decisions. Key questions include:

- Who will benefit or be harmed by this decision?

- What are the long-term effects on individuals and relationships?

- Does this decision demonstrate compassion and understanding?

This approach encourages leaders to move beyond a top-down hierarchy, fostering collaborative efforts and a sense of belonging among all stakeholders, including students, teachers, and families.

Beyond gender. While often associated with feminist scholars like Carol Gilligan and Nel Noddings, the ethic of care is not gender-specific. Many male ethicists and educators also champion its importance, recognizing that professions like education inherently involve a "caring business." It integrates reason and emotion, acknowledging that ethical decisions are often deeply intertwined with human feelings and the desire to foster well-being.

5. The Ethic of Critique: Challenging Power, Inequity, and the Status Quo

The ethic of critique is based on critical theory, which has, at its heart, an analysis of social class and its inequities.

Unmasking power dynamics. The ethic of critique challenges the underlying assumptions and power structures that often perpetuate inequities within society and schools. It questions "ethics approved by whom?" and "right or wrong according to whom?", pushing leaders to examine how privilege, social class, race, gender, and other differences influence decision-making and resource distribution. This paradigm aims to awaken educators to systemic injustices.

Asking hard questions. Critical theorists are concerned with making visible the voices of those who are silenced or marginalized. They prompt leaders to ask:

- Who makes the laws, and who benefits from them?

- Who holds power, and how is it exercised?

- Whose voices are missing from the conversation?

- How does the curriculum reproduce societal inequalities (the "hidden curriculum")?

This approach encourages a deep, investigative analysis of social structures and their impact on educational opportunities.

Action for transformation. Beyond mere questioning, the ethic of critique calls for action and transformation. It seeks to demystify existing norms and challenge the status quo, fostering a "language of possibility" that enables all children to grow, learn, and achieve, regardless of their background. This means actively working to dismantle "isms" (classism, racism, sexism, heterosexism) and empowering individuals and communities to create more just and democratic educational environments.

6. The Ethic of the Profession: Centering Decisions on the Student's Best Interests

If there is a moral imperative for the profession, it is to serve the “best interests of the student.”

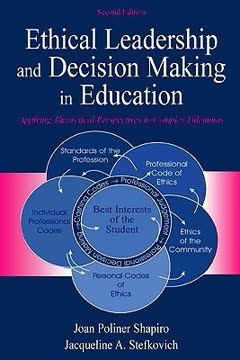

A distinct paradigm. While often subsumed under the ethic of justice, this book argues for the ethic of the profession as a standalone, crucial paradigm. It integrates elements from justice, care, and critique, but uniquely centers all ethical decision-making on the "best interests of the student." This imperative serves as the guiding principle for educational leaders, akin to "First, do no harm" in medicine.

Personal and professional codes. This paradigm emphasizes the dynamic process of developing one's own ethical framework. Leaders are encouraged to:

- Formulate personal codes based on life experiences and values.

- Create professional codes informed by their personal ethics, professional standards (like ISLLC), and community expectations.

- Identify and reconcile potential "clashes of codes" (e.g., personal vs. professional, within professions, among colleagues, or with community customs).

This self-reflective process ensures that decisions are grounded in a coherent and deeply considered ethical stance.

Beyond compliance. Professional ethics extends beyond merely adhering to formal codes or legal requirements. It demands professional judgment that is flexible, individualized, and responsive to the diverse needs of students and communities. It recognizes that "best interests of the student" involves balancing individual rights, fostering responsibility for actions, and demonstrating respect, ensuring that every decision contributes to the holistic success of each learner.

7. Real-World Dilemmas Emerge from Societal Paradoxes

Purpel (1989, 2004), in describing the moral and spiritual crisis in contemporary education, turned to paradoxes to bring out many current problems and tensions.

Inherent contradictions. The book frames real-life ethical dilemmas within the context of inherent societal paradoxes, highlighting the tensions that educational leaders constantly navigate. These contradictions, such as individual rights versus community standards or traditional curriculum versus hidden curriculum, are not easily resolved and often lead to complex moral quandaries.

Case study approach. Part II of the book presents a series of authentic case studies, each illustrating one of these paradoxes. Examples include:

- Individual Rights vs. Community Standards: A teacher's private life conflicting with community expectations.

- Traditional vs. Hidden Curriculum: Debates over age-appropriate sex education or culturally responsive teaching.

- Personal vs. Professional Codes: An administrator grappling with a colleague's personal conduct impacting their professional role.

- Melting Pot vs. Hot Pot: Cultural differences impacting child discipline or academic expectations for immigrant students.

- Religion vs. Culture: Conflicts arising from religious practices within public school settings.

- Equality vs. Equity: Challenges in inclusion programs or minority teacher retention.

- Accountability vs. Responsibility: Pressures from high-stakes testing leading to ethical compromises.

- Privacy vs. Safety: Navigating issues like drug searches, gang activity, cyber-bullying, or teachers' personal lives exposed via technology.

Stimulating reflection. By presenting these dilemmas, the book encourages readers to engage in thoughtful, complex thinking, applying the four ethical paradigms to come to grips with their own ethical codes and apply them to practical situations. This approach aims to foster wise decision-making in a world full of complexities and contradictions.

8. Self-Reflection is the Cornerstone of Ethical Leadership Development

We believe it is imperative that we all become reflective practitioners when attempting to solve ethical dilemmas.

Personal journey. Ethical leadership is not merely about applying external rules but about a deep, ongoing process of self-reflection. The book emphasizes that instructors and aspiring leaders must examine their own personal and professional ethical codes, understanding how their life experiences and values shape their perspectives and decisions. This introspection is crucial for developing authentic and consistent ethical practice.

Pedagogical imperative. For those teaching ethics, modeling self-reflection is paramount. The authors share their own "professors' stories," detailing critical incidents and influences (e.g., Civil Rights Movement, British education system, feminist scholarship, personal experiences with discrimination) that shaped their ethical frameworks. This transparency helps students understand that ethical codes are not static but evolve through lived experience and critical engagement.

Continuous growth. The process of developing ethical leadership is lifelong. It involves:

- Consciously examining one's own biases and assumptions.

- Comparing personal values with professional standards and societal expectations.

- Learning from successes and limitations in ethical decision-making.

- Engaging in difficult dialogues with diverse perspectives.

This continuous self-assessment empowers leaders to navigate moral ambiguities with greater integrity and wisdom, fostering a deeper understanding of themselves and their impact on others.

9. Diversity Enriches and Challenges Ethical Understanding

As one of our students, a White, male biology professor in a rural setting, pointed out: I believe that there is strength in diversity.

A mosaic of perspectives. The book highlights that diversity, broadly defined to include race, gender, age, religion, socio-economic status, and professional experience, is a profound strength in ethical discourse. Students from varied backgrounds bring unique insights to dilemmas, demonstrating that ethical views are not monolithic but are shaped by a confluence of factors. This rich tapestry of perspectives enriches classroom discussions and real-world problem-solving.

Navigating complexity. While a strength, diversity also presents significant challenges. Leaders must be acutely aware of:

- Subtle stereotypes and preconceived notions.

- Cultural nuances that influence ethical interpretations (e.g., the "melting pot" vs. "Chinese hot pot" metaphor).

- The need to act as "translators" across different cultural and ethical "borders."

This requires constant vigilance, challenging ingrained assumptions, and fostering an environment where all voices are heard and respected, even when they differ.

Empowering all voices. The ultimate goal is to empower educational leaders to appreciate and leverage diversity in their ethical decision-making. By engaging with a wide range of viewpoints, leaders can develop solutions that are not only just and caring but also culturally sensitive and inclusive. This prepares them to lead effectively in increasingly pluralistic school communities, ensuring that education serves the best interests of all children, recognizing their unique backgrounds and needs.

Last updated:

Review Summary

Ethical Leadership and Decision Making in Education receives mostly positive reviews, with readers praising its practical case studies and ethical frameworks. Many find the scenarios thought-provoking and valuable for educational leaders. The book's approach to ethical decision-making is appreciated, with some readers noting its impact on their perspective. Critics mention a lack of foundational ethical standards and occasionally ridiculous scenarios. Overall, reviewers recommend it as a helpful resource for educators and school leaders, highlighting its engaging introduction to ethical educational leadership.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.