Plot Summary

Rituals of Hunger and Control

Rachel's life is ruled by the strict rituals of eating, calorie counting, and self-denial. Her days are structured around food, nicotine gum, and the avoidance of hunger, which she equates with virtue and control. The world outside—her job in Hollywood, her coworkers, and the city itself—fades in importance compared to the internal drama of what she will or won't eat. Food is both her comfort and her enemy, a source of anticipation and shame. The reader is drawn into the anxious, compulsive logic of her daily existence, where every bite is measured, every indulgence a potential threat to her fragile sense of self-worth. The emotional tone is one of tension, longing, and a desperate need for order in a chaotic world.

Maternal Shadows and Inheritance

Rachel's relationship with her mother is fraught with judgment, shame, and the inheritance of disordered eating. Her mother's obsession with thinness, her constant comparisons, and her inability to offer unconditional love have left Rachel with a deep sense of inadequacy. The maternal voice is internalized, becoming both a source of pain and a standard Rachel cannot escape. Childhood memories of food, family, and Jewish identity are colored by this dynamic, as Rachel struggles to separate her own desires from the expectations imposed upon her. The emotional landscape is one of longing for approval, fear of rejection, and the ache of never being enough.

The Mathematics of Eating

Rachel's life is governed by the mathematics of eating: calories, portion sizes, and the constant calculation of what is "allowed." She fantasizes about forbidden foods, constructing elaborate daydreams of indulgence that she never permits herself in reality. The act of eating is ritualized, private, and deeply emotional. Even pleasure is tinged with guilt and the fear of losing control. The reader feels the intensity of her hunger—not just for food, but for comfort, satisfaction, and a sense of safety. The world of food becomes a battleground where Rachel wages war against her own body and desires.

Therapy, Boundaries, and Expectation

Rachel seeks help from Dr. Mahjoub, a therapist whose advice to set boundaries with her mother is both liberating and terrifying. The idea of a "communication detox" promises freedom, but also triggers guilt and grief. Therapy becomes a space where Rachel confronts the possibility of change, but also resists it, clinging to familiar patterns. The therapist's encouragement to "parent herself" is met with skepticism and self-loathing. Rachel's attempts to implement boundaries in real life are met with confusion and pushback, highlighting the difficulty of breaking free from deeply ingrained dynamics. The emotional arc is one of hope, resistance, and the painful process of growth.

Comedy, Performance, and Validation

Rachel's stand-up comedy is both an escape and a quest for validation. On stage, she transforms her pain into humor, seeking approval from strangers and peers alike. The world of comedy is competitive, performative, and often alienating. Rachel's longing to be seen and appreciated is palpable, as is her awareness of the gap between her public persona and private struggles. The laughter of the audience offers a fleeting sense of connection, but also underscores her isolation. The emotional tone is bittersweet, blending moments of triumph with the persistent ache of not quite fitting in.

The Gym and the Illusion of Freedom

The gym is another arena where Rachel seeks control, burning calories as a form of penance and self-discipline. The green glow of the elliptical machine's numbers offers a sense of accomplishment, but also reinforces her isolation. Exercise becomes a substitute for intimacy, a way to avoid vulnerability and connection. The rituals of working out mirror those of eating: precise, obsessive, and ultimately unsatisfying. The reader senses the emptiness beneath the surface, the longing for something more than the endless cycle of restriction and exertion.

Detoxing from Motherhood

Rachel's attempt to detox from her mother's influence is both empowering and excruciating. The silence that follows is filled with longing, regret, and the fear of abandonment. The absence of her mother's voice creates space for new experiences, but also leaves Rachel adrift. She mourns not just the loss of contact, but the loss of hope that her mother will ever change. The process of letting go is fraught with ambivalence, as Rachel grapples with the reality that freedom comes at a cost. The emotional arc is one of grief, resilience, and the tentative emergence of selfhood.

Ana: Maternal Longing and Desire

Ana, the office manager, becomes a surrogate mother figure for Rachel—one who offers both approval and the possibility of erotic desire. Rachel's fantasies about Ana blur the lines between maternal comfort and sexual longing, revealing the complexity of her needs. The absence of rejection from Ana feels like an embrace, a balm for the wounds inflicted by her own mother. Yet this relationship, too, is fraught with ambivalence, as Rachel navigates the boundaries between admiration, envy, and desire. The emotional tone is one of yearning, confusion, and the search for a nurturing presence.

Work, Authenticity, and Approval

Rachel's job in talent management is a microcosm of her larger battles with authenticity, approval, and self-worth. The performative nature of Hollywood, the pressure to fit in, and the constant surveillance of her choices echo the dynamics of her family life. Interactions with her boss, Ofer, and clients like Jace highlight the tension between external validation and internal emptiness. The workplace becomes another stage where Rachel performs, hides, and negotiates her identity. The emotional landscape is one of anxiety, resentment, and the longing to be seen for who she truly is.

Sculpting Fear, Facing Self

In a pivotal therapy session, Rachel is asked to sculpt her fears out of clay. The act of creating a physical representation of her "out of control" self brings buried anxieties to the surface. The figure she sculpts is both alien and intimately familiar—a manifestation of the body she dreads becoming, but also a part of herself she cannot deny. The experience is cathartic and unsettling, forcing Rachel to confront the possibility that even her most feared self is worthy of love. The emotional arc is one of vulnerability, revelation, and the painful beauty of self-acceptance.

Miriam: The Fat Yogurt Girl

Miriam, the new server at Yo!Good, is everything Rachel fears: fat, unapologetic, and at ease in her own body. Her presence challenges Rachel's assumptions about beauty, worth, and desire. Miriam's confidence and generosity with food unsettle Rachel, forcing her to confront her own prejudices and insecurities. The growing connection between them is fraught with tension, attraction, and the possibility of transformation. Miriam becomes both a mirror and a catalyst, inviting Rachel to imagine a different way of being in the world. The emotional tone is one of fascination, fear, and the stirrings of hope.

Toppings, Shame, and Temptation

Miriam's insistence on generous servings and toppings pushes Rachel to the edge of her comfort zone. The act of eating becomes a site of both pleasure and shame, as Rachel battles the urge to indulge and the fear of losing control. The rituals of discarding excess yogurt, hiding her consumption, and navigating public exposure highlight the deep-seated anxieties that govern her relationship with food. Yet, in moments of surrender, Rachel experiences a joy and freedom she has long denied herself. The emotional arc is one of temptation, guilt, and the possibility of pleasure without punishment.

Fathers, Variety, and Longing

Rachel's relationship with her father contrasts sharply with that of her mother. He is permissive, indulgent, and largely absent, offering her the forbidden foods her mother denies. Their time together is marked by excess, variety, and a fleeting sense of abundance. Yet this indulgence is temporary, always followed by loss and the return to restriction. The "variety pack" becomes a symbol of both possibility and sadness—a reminder of what is given and taken away. The emotional tone is one of nostalgia, longing, and the ache of unmet needs.

Sprinkles, Surrender, and Binge

When Miriam offers Rachel a sundae covered in sprinkles, Rachel is overcome by pleasure and shame. The act of eating becomes ecstatic, almost transcendent, as she surrenders to sensation and desire. Yet the aftermath is filled with guilt, fear, and the compulsion to compensate through restriction. The binge that follows is both a release and a punishment, a desperate attempt to fill an emptiness that food cannot satisfy. The emotional arc is one of abandon, regret, and the cyclical nature of hunger and self-denial.

Parties, Hunger, and Hiding

At industry parties and social gatherings, Rachel's anxieties about food, body, and belonging are heightened. Surrounded by the ultra-thin and the professionally beautiful, she feels exposed and inadequate. The rituals of sneaking food, eating in bathrooms, and hiding her hunger underscore the isolation that pervades her life. The desire for approval, both from others and herself, is ever-present, yet always out of reach. The emotional tone is one of alienation, longing, and the persistent search for safety.

Miriam's Sundae: Crossing Lines

The deepening relationship with Miriam becomes a site of both liberation and fear. Sharing food, pleasure, and eventually physical intimacy, Rachel begins to experience a new kind of connection—one that challenges her old patterns of control and self-denial. The boundaries between hunger, desire, and love blur, as Rachel allows herself to be vulnerable and open to joy. Yet this crossing of lines also brings anxiety, as she grapples with the risks of intimacy and the possibility of loss. The emotional arc is one of awakening, courage, and the bittersweet taste of hope.

The Binge and Its Aftermath

After a day of unrestrained eating, Rachel is left with a mix of satisfaction and self-loathing. The physical discomfort is matched by emotional pain, as she confronts the consequences of her actions. The cycle of restriction and indulgence is laid bare, revealing the futility of seeking fulfillment through food alone. Yet in the aftermath, there is also a glimmer of acceptance—a recognition that the pursuit of perfection is both impossible and destructive. The emotional tone is one of exhaustion, reflection, and the tentative beginnings of self-compassion.

Golem, Guilt, and Jewish Monsters

Rachel's struggles are reframed through the lens of Jewish folklore, particularly the story of the golem—a creature made from clay, animated by longing and fear. The golem becomes a metaphor for Rachel's own unfinished self, her hunger, and her search for meaning. The interplay of guilt, tradition, and identity adds depth to her journey, as she seeks to reconcile her desires with her heritage. The emotional arc is one of mythic resonance, self-examination, and the search for wholeness.

The Return of the Mother

Despite the detox, Rachel's mother remains a powerful force in her life, her voice echoing in moments of vulnerability and change. The possibility of reconciliation is fraught with ambivalence, as Rachel weighs the costs and benefits of connection. The longing for maternal approval persists, even as Rachel begins to forge her own path. The emotional tone is one of ambivalence, hope, and the enduring complexity of mother-daughter bonds.

Challah, Levitation, and Desire

In a moment of mystical vision, Rachel imagines herself levitating with a giant challah, symbolizing both spiritual and physical hunger. The boundaries between the sacred and the sensual dissolve, as desire becomes a form of transcendence. The relationship with Miriam deepens, blending eroticism, comfort, and the longing for belonging. The emotional arc is one of wonder, fulfillment, and the recognition that pleasure and holiness can coexist.

Women, Sex, and Fantasy

Rachel reflects on her past experiences with women, the complexities of desire, and the ways in which fantasy often outstrips reality. The tension between longing and satisfaction, between the imagined and the actual, is palpable. The relationship with Miriam offers the possibility of genuine connection, but also stirs old fears and insecurities. The emotional tone is one of curiosity, vulnerability, and the ongoing process of self-discovery.

Peppermint Plotz and Invitation

Miriam's creation of the Peppermint Plotz sundae becomes a symbol of generosity, creativity, and the invitation to deeper intimacy. The act of sharing food becomes a prelude to sharing life, as Rachel is drawn further into Miriam's world. The boundaries between pleasure, nourishment, and love continue to blur, offering the possibility of healing and transformation. The emotional arc is one of anticipation, delight, and the courage to accept joy.

Gifts, Fantasies, and Fear

Rachel's impulse to give Miriam gifts reflects both her affection and her fear of rejection. The act of giving becomes a way to test boundaries, express longing, and seek reassurance. The interplay of fantasy and reality is ever-present, as Rachel navigates the uncertainties of new love. The emotional tone is one of tenderness, insecurity, and the hope that vulnerability will be met with acceptance.

Dinner, Drinks, and God

Sharing a meal at the Golden Dragon, Rachel and Miriam explore questions of faith, identity, and the meaning of connection. The conversation is playful, profound, and charged with unspoken desire. The act of eating together becomes a ritual of intimacy, a way to bridge differences and affirm shared values. The presence of God, tradition, and family hovers in the background, shaping the possibilities and limits of their relationship. The emotional arc is one of discovery, joy, and the recognition of the sacred in the everyday.

The Miracle of Eating Together

The experience of sharing food with Miriam and her family offers Rachel a glimpse of unconditional belonging. The rituals of Shabbat, the abundance of the table, and the warmth of hospitality contrast sharply with her history of deprivation and exclusion. Yet this acceptance is conditional, bounded by tradition and the limits of what can be spoken or shown. The emotional tone is one of gratitude, longing, and the bittersweet awareness of what is possible—and what is not.

Fortune Cookies and Intimacy

The exchange of fortune cookies, lipstick, and playful banter becomes a way for Rachel and Miriam to express affection and test the boundaries of their relationship. The intimacy of shared secrets, private jokes, and physical touch grows, even as the constraints of family and tradition loom. The emotional arc is one of playfulness, desire, and the slow unfolding of trust.

Movie Theater Hands

In the darkness of the movie theater, Rachel and Miriam's relationship becomes explicitly physical, as they hold hands, touch, and explore the boundaries of what is allowed. The thrill of secrecy, the fear of exposure, and the joy of connection are all present. The act of holding hands becomes a profound gesture of intimacy, signaling both the possibility and the risk of love. The emotional tone is one of excitement, vulnerability, and the sweetness of first love.

The Hi Texts and Mother's Silence

As Rachel's relationship with Miriam deepens, her mother's absence becomes more pronounced. The daily "Hi" texts are both a lifeline and a reminder of what is missing. The longing for maternal connection persists, even as Rachel begins to find fulfillment elsewhere. The emotional arc is one of ambivalence, mourning, and the slow process of letting go.

Stand-Up, Jace, and Hot Dogs

Rachel's interactions with Jace, her stand-up performances, and her forays into casual sex reflect her ongoing search for approval and belonging. The desire to be wanted, to be seen as attractive and valuable, is ever-present. Yet these encounters often leave her feeling empty, highlighting the difference between external validation and genuine connection. The emotional tone is one of restlessness, disappointment, and the persistent hunger for more.

Sex, Disappointment, and Self-Discovery

Rachel's experiences with Jace and others underscore the gap between fantasy and reality, between what she thinks she wants and what actually satisfies. The act of sex becomes a mirror for her emotional state, revealing both her desires and her limitations. The journey toward self-acceptance is ongoing, marked by moments of pleasure, confusion, and the recognition that fulfillment cannot be found in others alone.

Shabbat at the Schwebels

Rachel's immersion in Miriam's family life offers a vision of belonging, comfort, and continuity. The rituals of Shabbat, the abundance of food, and the warmth of the Schwebels' home contrast with Rachel's own history of isolation and deprivation. Yet this acceptance is fragile, bounded by unspoken rules and the ever-present threat of exclusion. The emotional arc is one of hope, gratitude, and the awareness of the limits of belonging.

Forbidden Love, Family, and Exile

The deepening relationship between Rachel and Miriam comes into conflict with the expectations of family, community, and tradition. The risk of exposure, the pain of rejection, and the fear of exile loom large. The possibility of love is both exhilarating and terrifying, offering the promise of fulfillment and the threat of loss. The emotional tone is one of tension, heartbreak, and the courage to choose oneself.

Daughterhood, Self-Love, and Letting Go

In the aftermath of loss, Rachel turns inward, seeking to mother herself and embrace her own daughterness. The journey toward self-love is fraught with difficulty, but also marked by moments of grace and acceptance. The recognition that she can be both mother and daughter to herself offers a new kind of freedom—a way to hold her own pain, nurture her own joy, and move forward with compassion. The emotional arc is one of healing, integration, and the quiet power of self-acceptance.

Reunion, Closure, and Unfinished Substance

Years later, Rachel encounters Miriam again, now a mother herself. The brief, wordless exchange is suffused with recognition, gratitude, and the knowledge that their love, though unfinished, was real. The story ends with a sense of peace, the acknowledgment that life is an ongoing process of becoming, and that love—however brief—leaves its mark. The emotional tone is one of closure, acceptance, and the gentle embrace of what was, what is, and what might yet be.

Characters

Rachel

Rachel is the novel's narrator and protagonist, a young Jewish woman living in Los Angeles, whose life is dominated by disordered eating, obsessive rituals, and a fraught relationship with her mother. Her psyche is shaped by a deep sense of inadequacy, a longing for approval, and the internalized voice of maternal judgment. Rachel's journey is one of self-discovery, as she navigates the complexities of desire, intimacy, and identity. Her relationships—with food, with women, with her parents, and with herself—are marked by ambivalence, longing, and the persistent hope for healing. Over the course of the novel, Rachel moves from self-denial and isolation toward moments of connection, pleasure, and self-acceptance, though her struggles remain ongoing and unresolved.

Miriam

Miriam is the "fat yogurt girl" at Yo!Good, whose unapologetic presence and generosity with food challenge Rachel's assumptions about beauty, worth, and love. Miriam is confident, nurturing, and at ease in her own body, yet also bound by the expectations of her Orthodox Jewish family. Her relationship with Rachel is transformative, offering both the possibility of healing and the risk of heartbreak. Miriam's journey is one of self-assertion, as she navigates the tension between tradition and desire, family and autonomy. She becomes both a mirror and a catalyst for Rachel, inviting her to imagine a different way of being in the world.

Rachel's Mother

Rachel's mother is a powerful, often absent presence in the novel, whose obsession with thinness, control, and propriety has left deep scars on Rachel's psyche. She is both a source of comfort and a source of pain, embodying the contradictions of maternal love. Her inability to offer unconditional acceptance drives much of Rachel's anxiety and self-doubt. The mother-daughter relationship is central to the novel's exploration of inheritance, identity, and the struggle to break free from destructive patterns.

Ana

Ana is the office manager at Rachel's workplace, a woman whose elegance, sharp wit, and subtle kindness make her both a maternal figure and an object of erotic fantasy. Ana offers Rachel a sense of belonging and approval, yet their relationship is also marked by competition, envy, and the limits of surrogate intimacy. Ana's own wounds and disappointments mirror Rachel's, highlighting the ways in which women seek comfort and validation from one another.

Dr. Mahjoub

Dr. Mahjoub is Rachel's therapist, a calm and practical presence who encourages Rachel to set boundaries, confront her fears, and "parent herself." Her advice is both empowering and frustrating, as Rachel resists change and clings to familiar patterns. Dr. Mahjoub's role is to hold up a mirror to Rachel's struggles, offering insight and support while respecting her autonomy. The therapeutic relationship is a site of both hope and resistance, reflecting the challenges of personal growth.

Jace

Jace is a young actor represented by Rachel's firm, whose attention and approval become a source of excitement and anxiety for Rachel. He embodies the allure of external validation, the fantasy of being wanted by someone "certified hot." Yet their sexual encounter is ultimately unsatisfying, highlighting the gap between fantasy and reality, and the limitations of seeking fulfillment through others.

Ofer

Ofer is Rachel's boss, a well-meaning but oblivious figure who embodies the contradictions of Hollywood's "family" culture. He is both supportive and condescending, enforcing the rules of the workplace while failing to see Rachel's true struggles. Ofer's role is to maintain order, reward conformity, and punish transgression, serving as a stand-in for the larger systems of power that shape Rachel's world.

Rachel's Father

Rachel's father offers a counterpoint to her mother: permissive, loving in his own way, but largely absent. Their relationship is marked by moments of indulgence and excess, followed by loss and disappointment. He represents the possibility of comfort without judgment, but also the limitations of love that is not fully present.

Mrs. Schwebel

Mrs. Schwebel is the matriarch of Miriam's family, a warm and generous hostess whose acceptance is conditional on adherence to tradition. She embodies the comforts and constraints of family, offering Rachel a glimpse of belonging while also enforcing the boundaries of what is permissible. Her reactions to Rachel and Miriam's relationship highlight the tensions between love, loyalty, and the demands of community.

Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel (Dream Figure)

The rabbi appears in Rachel's dreams as a mystical, humorous figure who offers guidance, comfort, and perspective. He represents the intersection of tradition, myth, and personal transformation, reminding Rachel of the unfinished nature of the self and the ongoing process of becoming.

Plot Devices

Ritual, Repetition, and Obsession

The novel is built around the obsessive rituals of eating, exercising, and self-monitoring that define Rachel's life. These routines serve as both a source of comfort and a prison, mirroring the cyclical nature of addiction, anxiety, and the search for control. The repetition of behaviors, thoughts, and fantasies creates a sense of claustrophobia, but also highlights the possibility of change through small acts of rebellion or surrender.

Food as Symbol and Battleground

Food is the central symbol of the novel, representing everything from comfort and pleasure to shame, punishment, and longing. The act of eating is fraught with meaning, serving as a battleground for issues of control, identity, and self-worth. Shared meals become sites of intimacy and transformation, while binges and restrictions reveal the depths of Rachel's hunger—for love, acceptance, and belonging.

Maternal Inheritance and the Golem Motif

The motif of the golem—a creature made from clay, animated by longing and fear—serves as a metaphor for Rachel's own unfinished self. The inheritance of maternal trauma, the search for wholeness, and the tension between tradition and autonomy are all reframed through the lens of Jewish folklore. The golem becomes a symbol of both the dangers and the possibilities of creation, transformation, and self-acceptance.

Therapy and Self-Reflection

The therapeutic relationship with Dr. Mahjoub provides a framework for self-examination, insight, and the possibility of change. Therapy sessions serve as narrative turning points, prompting Rachel to confront her fears, set boundaries, and imagine new ways of being. The process is nonlinear, marked by resistance, regression, and moments of revelation.

Foreshadowing and Dream Sequences

The novel makes extensive use of dream sequences, fantasies, and internal monologues to foreshadow events, reveal hidden desires, and explore the unconscious. These moments blur the boundaries between reality and imagination, highlighting the complexity of Rachel's inner world and the ongoing process of integration.

Narrative Structure: Fragmented, Cyclical, and Intimate

The narrative is fragmented and cyclical, moving between past and present, memory and fantasy, ritual and rupture. This structure mirrors the rhythms of obsession, the recurrence of trauma, and the slow, nonlinear process of healing. The intimate, confessional voice draws the reader into Rachel's experience, creating a sense of immediacy and vulnerability.

Analysis

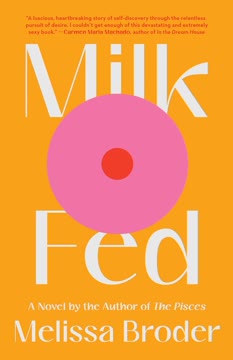

Milk Fed is a raw, intimate exploration of hunger in all its forms—physical, emotional, spiritual, and erotic. Through Rachel's obsessive rituals, fraught relationships, and journey toward self-acceptance, Melissa Broder crafts a narrative that is both deeply personal and universally resonant. The novel interrogates the ways in which women inherit and internalize shame, the longing for maternal approval, and the struggle to claim pleasure and autonomy in a world that polices bodies and desires. Food becomes the central metaphor, embodying the tensions between control and surrender, deprivation and abundance, isolation and connection. The relationship between Rachel and Miriam offers a vision of radical acceptance, challenging the boundaries of tradition, identity, and love. Yet the novel resists easy resolutions, acknowledging the persistence of longing, the complexity of healing, and the unfinished nature of the self. In a culture obsessed with perfection, Milk Fed insists on the beauty of the unfinished, the power of vulnerability, and the possibility of finding nourishment—in all its messy, imperfect forms—within and between ourselves.

Last updated:

Review Summary

Milk Fed by Melissa Broder has received mixed reviews. Many readers found it raw, honest, and darkly comic, appreciating its exploration of themes like disordered eating, sexuality, and mother-daughter relationships. The protagonist, Rachel, resonated with some readers, while others found her difficult to like. The explicit sexual content and graphic descriptions of eating disorders were polarizing. Some praised Broder's sharp writing and humor, while others felt the novel lacked substance or coherence. Overall, it's a divisive book that seems to provoke strong reactions.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.