Plot Summary

The Psychologist's Strange Drawing

Dr. Tomiko Hagio, a psychologist turned professor, presents her students with a child's drawing: a girl with a smudged mouth, a house with no door, and a tree with thorny branches. The drawing, made by "Little A," an eleven-year-old girl arrested for her mother's murder, is dissected for clues to her psyche. The smudged mouth reveals the pain of forced smiles under abuse; the doorless house, a longing for refuge; the thorny tree, a defensive aggression. Yet, within the tree's trunk, a small bird in a hollow suggests a hidden, nurturing love. Hagio concludes that, despite the violence, the girl's core is kind and capable of rehabilitation. This sets the stage for a story where art, trauma, and hidden truths intertwine, and where pictures become mirrors of the soul's deepest wounds and hopes.

Blog of Hidden Sorrows

Shuhei Sasaki, a college student, stumbles upon a blog recommended by his friend Kurihara. The blog, "Oh No, not Raku!," chronicles the seemingly ordinary life of Raku and his wife Yuki, a former illustrator. The entries begin with joy—wedding anniversaries, pregnancy, and dreams for their unborn child. But as Yuki's pregnancy progresses, complications arise: the baby is breech, and anxiety mounts. Yuki draws a series of "visions of the future" for their child, each marked with mysterious numbers. Suddenly, tragedy strikes—Yuki dies during childbirth, leaving Raku and their newborn alone. The blog abruptly halts, only to resume years later with a cryptic, grief-stricken post: "I cannot forgive you. But even so, I will always love you." The blog's innocent surface hides a labyrinth of pain, secrets, and unresolved guilt.

Three Visions, Three Secrets

Sasaki and Kurihara obsess over the blog's final entries, especially the "three drawings" Yuki left behind. The pictures—of a baby, an old woman, and an adult—are layered with hidden meaning. By analyzing the numbers and aligning the images, they discover a chilling optical illusion: the drawings, when stacked, depict a caesarean birth, a lifeless mother, and a figure extracting the child. The "visions of the future" are not hopeful fantasies but a premonition of Yuki's own death. The numbers, circles, and composition reveal Yuki's awareness of her impending fate—possibly even a murder disguised as medical tragedy. The blog's cryptic language and the deleted entries after Yuki's death suggest a deeper, unspoken trauma, and the drawings become a silent, desperate message to those left behind.

A Child's Scribbled Cry

In a Tokyo apartment, Naomi Konno struggles as a single mother to Yuta, a sensitive boy who loves to draw. After a tense episode where Yuta is scolded for drawing on the walls, he creates a Mother's Day picture at nursery school. The drawing shows their apartment building, but the family's room is covered by a heavy grey scribble. Teachers and Naomi puzzle over the meaning: is it shame, fear, or a secret? The process of analyzing the drawing—tracing the order of lines, the use of color, and the emotional context—reveals that Yuta first drew a shape, then tried to erase it, then drew the building over it. The act of hiding something in the drawing hints at a deeper anxiety or trauma, and the adults around Yuta begin to fear for his well-being.

Shadows in the Apartment Hallway

Naomi becomes convinced that someone is following her and Yuta. A mysterious man in a grey coat lurks near their building, and his presence escalates Naomi's anxiety. One night, as they rush home, the man follows them up the stairs, and Naomi barely manages to get inside and lock the door. The sense of being hunted, combined with her own exhaustion and guilt, leaves Naomi on edge. She is haunted by the possibility that her past is catching up with her, and that Yuta is in danger. The next morning, she oversleeps and discovers Yuta is missing. Panic sets in, and the narrative shifts to a desperate search, as the boundaries between real threats and psychological shadows blur.

The Missing Boy and the Grave

Yuta's disappearance triggers a frantic search by Naomi and his nursery school teacher, Ms. Haruoka. As the adults retrace his steps, clues from Yuta's drawing and memories point to a cemetery. Yuta, it turns out, has gone to visit the grave of his birth mother, Yuki, guided by a faint childhood memory and the kanji of his family name. The journey is both literal and symbolic—a child's longing to connect with his lost origins, and a mother's fear of losing her child. When Naomi finds Yuta at the cemetery, relief and sorrow mingle. The episode exposes the tangled web of family, loss, and the silent burdens children carry, often expressed only through their art.

The Art Teacher's Last Message

Years earlier, art teacher Yoshiharu Miura is found brutally murdered on Mt. K—. The case, investigated by reporter Kumai and later by his protégé Iwata, is shrouded in mystery. Miura's last act was to draw a crude picture of the mountain view on the back of a receipt, using grid lines as if drawing blind. The police focus on Miura's friend Toyokawa, but lack evidence. Interviews with students and colleagues reveal Miura as a strict, sometimes disliked teacher, but also a man capable of deep kindness. The drawing, left at the scene, becomes the key to unraveling the truth—a dying message whose meaning eludes everyone for years.

The Mountain's Deadly Puzzle

Driven by loyalty to his mentor, Iwata investigates Miura's murder, reconstructing the timeline and interviewing those involved. He learns of rivalries, unrequited love, and the complex relationships between Miura, Toyokawa, and student Yuki Kameido. Iwata's own journey up the mountain mirrors Miura's final day. He realizes that the time of death was faked by force-feeding Miura a bento to mislead the autopsy, and that the missing sleeping bag and food were part of the deception. The drawing, made with hands bound behind the back, is a coded message: "I survived until morning." The real killer is not Toyokawa, but someone with a deeper motive and a mother's protective rage.

Dying Messages in Lines and Light

The motif of hidden messages in art recurs: Yuki's layered drawings, Yuta's scribbled apartment, Miura's mountain sketch, and Iwata's final picture. Each is a desperate attempt to communicate when words fail—whether to warn, confess, or protect. The act of drawing blind, using folds or touch, symbolizes the struggle to leave a trace of truth in the face of violence and erasure. The killer, it is revealed, is Naomi, who murdered to protect her son and later her grandson, manipulating evidence and exploiting the trust of those around her. The cycle of violence is perpetuated by love twisted into obsession, and by the inability to break free from the past.

The Web of Mothers and Sons

Naomi's life is revealed in full: abused by her own mother, she killed to protect her pet bird, then spent years in a reformatory. As an adult, she becomes a midwife, marries Miura, and raises Haruto, pouring all her love into him but stifling his independence. When Haruto marries Yuki, Naomi's jealousy and fear of losing her role as "mother" drive her to murder Yuki through subtle means—salt capsules disguised as supplements. Haruto, unable to reconcile love and betrayal, eventually takes his own life. Naomi's actions, always justified as protection, leave a trail of tragedy, and the children—Haruto, Yuta—bear the scars of secrets and unspoken pain.

The Old Woman's Confession

Reporter Kumai, haunted by guilt and a terminal diagnosis, orchestrates a confrontation with Naomi. He stalks her, provoking her into attacking him, and survives thanks to a bulletproof vest. Naomi is arrested, and her history of violence and manipulation is exposed. The psychologist Hagio, who once believed Naomi could be rehabilitated, is forced to reconsider her diagnosis. The tree with thorns, once a symbol of hidden kindness, now appears as a warning: protection can become aggression, and love can justify any crime. Naomi, in her cell, reflects on her life—a chain of protection, harm, and loss, all rooted in the desperate need to be needed.

The Trap for a Killer

Kumai's plan, aided by detective Kurata, ensures Naomi's arrest and the reopening of old murder cases. The narrative reveals how the legal system, the press, and personal vendettas intersect. Kumai's own motivations are complex: part guilt, part pride, part a need to prove himself before dying. The story questions the nature of justice—whether it is ever truly served, and whether the cycle of violence can be broken. The children left behind, especially Yuta, become the focus of concern: who will care for them, and can they escape the legacy of their family's secrets?

The Tree with Thorns

The recurring image of the tree with thorns and the bird in the hollow is revisited. Once seen as a sign of hope and nurturing, it now carries a darker meaning: the thorns protect, but also isolate and wound. Naomi's life is a testament to the dangers of love that becomes possessive and violent. The psychologist Hagio, reflecting on her earlier optimism, wonders if she misread the signs—if the very traits that seemed redeemable were, in fact, the seeds of future harm. The story asks whether cycles of trauma can ever be healed, or if they simply take new forms in each generation.

The Bird in the Hollow

In the aftermath of Naomi's arrest, Yuta is placed in an orphanage. The adults around him—teachers, neighbors, and Kumai—struggle to find a way to support him. The final scenes focus on small acts of kindness: a barbecue invitation, a plate of stir-fried noodles, a promise to look after the boy. The bird in the hollow, once a symbol of Naomi's hidden love, now becomes a symbol of Yuta's vulnerability and the hope that, despite everything, he might find a safe place to grow. The story ends not with resolution, but with the fragile possibility of healing.

The Cycle of Protection and Harm

The narrative circles back to its central theme: the ways in which love, especially maternal love, can both save and destroy. Naomi's life is a case study in how trauma begets trauma, and how the urge to protect can become a justification for harm. The story's structure—layered narratives, hidden messages, and intergenerational echoes—mirrors the complexity of real families and the difficulty of breaking free from inherited pain. The final lesson is ambiguous: there is no simple redemption, only the ongoing struggle to choose kindness over fear, and to recognize the thorns within ourselves.

The Final Barbecue

The story closes with a neighborhood barbecue, where Yuta, now orphaned, is welcomed by the Yonezawa family and watched over by Kumai, who has survived his surgery. The simple act of sharing food becomes a gesture of community and care. Miu, Yuta's friend, insists that he prefers noodles to meat, and her father obliges, determined to bring a little joy to the children. The cycle of violence and loss is not erased, but the possibility of new connections and gentle kindness remains. The bird, once threatened, may yet find safety in the tree.

Characters

Naomi Konno

Naomi is the central figure whose life is marked by trauma, resilience, and ultimately, violence. Abused as a child, she kills her mother to protect her pet bird, then spends years in a reformatory. As an adult, she becomes a midwife, marries Miura, and pours all her love into her son Haruto, but her love is possessive and suffocating. When Haruto marries Yuki, Naomi's fear of losing her role as "mother" drives her to murder Yuki through subtle means. She later kills to protect Haruto and Yuta, justifying her actions as maternal instinct. Naomi's psyche is a tangle of love, guilt, and denial; she is both victim and perpetrator, protector and destroyer. Her development is a tragic arc from abused child to abuser, unable to break the cycle of harm.

Haruto Konno (Raku)

Haruto, Naomi's son, is sensitive, introverted, and deeply attached to his mother. His blog, written under the pseudonym Raku, chronicles his life with Yuki and the birth of their child, but is haunted by loss and guilt. Haruto is unable to reconcile his love for Naomi with the realization of her crimes, especially after deciphering Yuki's hidden message in the drawings. His inability to break free from Naomi's influence leads to his own suicide, a final act of despair and unresolved conflict. Haruto's character embodies the tragedy of children who cannot escape the emotional gravity of their parents, and whose love becomes a source of suffering.

Yuki Konno (née Kameido)

Yuki is Haruto's wife, a former illustrator whose drawings become the key to unraveling the family's secrets. Sensitive and creative, she is beloved by Haruto and admired by others, but her life is cut short by Naomi's jealousy and manipulation. Yuki's "visions of the future" are both hopeful and ominous, containing a coded warning about her fate. Her silence in the face of Naomi's subtle violence is both an act of self-sacrifice and a tragic resignation. Yuki's legacy is her art, which becomes a lifeline for those seeking the truth.

Yuta Konno

Yuta is the son of Haruto and Yuki, raised by Naomi after his mother's death. Sensitive and artistic, he expresses his emotions through drawings, which become a silent cry for help. Yuta's journey—from confusion and anxiety to a desperate search for his origins—mirrors the larger themes of the novel: the search for identity, the burden of family secrets, and the hope for safety. Yuta's resilience is tested by loss and trauma, but the story ends with a glimmer of hope that he may find healing in the care of others.

Yoshiharu Miura

Miura, Naomi's husband and Haruto's father, is an art teacher whose murder becomes a central mystery. He is both feared and respected by students, and his relationships with colleagues are complex. Miura's final act—drawing a coded message while dying—reveals his intelligence and his desire to protect his family, even at the cost of his own life. His character is a study in contradictions: harsh yet caring, flawed yet noble. Miura's death sets off a chain of events that reverberate through the lives of those he left behind.

Nobuo Toyokawa

Toyokawa is Miura's former classmate, a talented but embittered artist who resents Miura's success. After Miura's death, Toyokawa becomes a threat to Naomi, using his knowledge of her crime to extort her. His actions are driven by jealousy, wounded pride, and a desire for revenge. Toyokawa's eventual suicide (or possible murder) is the result of being ensnared in Naomi's web of secrets. He represents the destructive power of unresolved resentment and the dangers of proximity to toxic relationships.

Shunsuke Iwata

Iwata is a young reporter inspired by Miura's murder to pursue journalism. Loyal, idealistic, and determined, he uncovers the truth behind the mountain murder, only to become a victim himself. Iwata's journey is one of growth and disillusionment; he learns that seeking the truth can be dangerous, and that justice is often elusive. His death is a turning point, forcing others to confront the consequences of their actions and the limits of their understanding.

Isamu Kumai

Kumai is an older journalist, once a star reporter, now sidelined by illness and regret. Haunted by his role in Iwata's death and the unsolved murders, he becomes obsessed with catching Naomi. Kumai's motivations are complex: guilt, pride, and a need to prove himself before dying. His final act—provoking Naomi into attacking him and ensuring her arrest—is both self-sacrificial and redemptive. Kumai's character embodies the tension between professional duty and personal responsibility, and the costs of pursuing justice.

Tomiko Hagio

Dr. Hagio is the psychologist who first analyzed Naomi as a child, believing her capable of rehabilitation. Her interpretation of Naomi's drawing—a tree with thorns and a bird—shapes the novel's central metaphor. As the truth of Naomi's crimes emerges, Hagio is forced to confront the limits of her own understanding and the dangers of optimism untempered by caution. Her character represents the struggle of those who seek to heal, but must also reckon with the reality of human darkness.

Miu Yonezawa

Miu is Yuta's classmate and friend, a bright and observant child who provides moments of levity and support. Her family's warmth and generosity offer a contrast to the Konno family's turmoil. Miu's role, though minor, is crucial in showing that healing and connection are possible, even in the aftermath of tragedy. She represents the hope that children, given care and understanding, can break free from cycles of pain.

Plot Devices

Layered Narratives and Hidden Messages

The novel employs a complex structure of nested narratives: blogs, drawings, interviews, and memories. Each layer reveals new facets of the central mystery, and the act of interpretation—by psychologists, teachers, reporters, and children—becomes a central motif. Art is not merely decoration but a vehicle for coded messages, confessions, and warnings. The use of optical illusions, anagrams, and layered drawings mirrors the psychological complexity of the characters. Foreshadowing is achieved through repeated motifs (the tree, the bird, the smudged mouth), and the narrative structure itself becomes a puzzle for the reader to solve. The interplay between what is seen and what is hidden, what is said and what is meant, drives the suspense and emotional impact of the story.

Analysis

"Strange Pictures" is a psychological mystery that uses the language of art to explore the deepest wounds of the human heart. At its core, the novel is about the ways in which trauma is transmitted across generations, and how the urge to protect can become a justification for harm. The story challenges the reader to question easy distinctions between victim and perpetrator, love and violence, healing and harm. Through its intricate structure and use of art as both evidence and metaphor, the novel asks whether it is possible to truly know another person—or even oneself. The lessons are sobering: that kindness and aggression can coexist, that secrets fester in silence, and that the search for safety can lead to new forms of danger. Yet, amid the darkness, the story offers a fragile hope: that through empathy, community, and the courage to face the truth, cycles of pain can be interrupted, if not entirely broken. The final image—a child welcomed at a barbecue, a bird safe in the tree—suggests that healing is possible, but only through the patient work of care and connection.

Last updated:

Review Summary

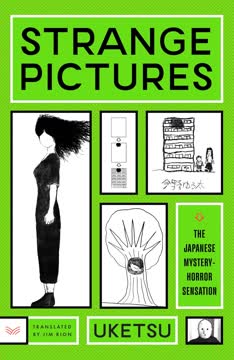

Strange Pictures is a uniquely structured mystery novel combining text and illustrations. Readers praise its innovative format, intricate plot, and unexpected twists, comparing it to puzzle-solving. Many enjoy the psychological aspects and interconnected stories. Critics note simple prose and repetitive explanations, possibly due to translation. The book polarizes readers, with some finding it brilliant and others boring. Overall, it's seen as an entertaining, quick read that challenges readers to piece together clues and unravel a complex mystery.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.