Key Takeaways

1. Ecology shapes the delta's destiny.

without the Himalayas, Bangladesh would not exist.

A land of water and silt. Bangladesh is fundamentally shaped by its geography, formed by the immense silt deposits carried by rivers flowing from the Himalayas. This process created the world's largest river delta, a vast floodplain crisscrossed by numerous waterways, including the mighty Ganges (Padma) and Brahmaputra (Jamuna). The delta's low elevation makes it highly susceptible to the forces of nature.

Three forms of water. Life in Bangladesh is dominated by river water, monsoon rain, and seawater.

- Rivers: Deposit fertile silt but constantly change course, causing floods and forcing settlements to relocate.

- Rain: Torrential monsoon rains from June to September contribute significantly to annual inundation.

- Seawater: Tidal bores from tropical cyclones and saline intrusion during the dry season impact coastal areas.

Nature's power. These natural forces exert enormous influence, acting as protagonists in history. Uncontrolled summer flooding is a way of life, varying yearly in timing, location, and extent. While annual floods replenish fertile soils, severe inundation can cause immense damage to crops, property, and lives, demonstrating that managing the natural environment has always been a central concern for societies and states in the delta.

2. Ancient origins laid the foundation for society.

Ever since, rice has shaped the history of Bangladesh.

Early human presence. Humans have inhabited the Bengal delta for tens of thousands of years, possibly using it as a thoroughfare for migration across Asia. Early evidence comes from stone tools found in surrounding hills, but the humid climate and lack of stone in the floodplains limit archaeological findings from the delta itself. Early inhabitants likely relied on wood, bamboo, and mud.

Rise of agriculture. Cultivation and animal domestication occurred before 1500 BCE. The development of irrigated rice cultivation on permanent fields was a crucial shift, requiring social systems to mobilize labor for field construction and maintenance. This productive agriculture became the foundation for all subsequent societies and states.

- Rice (dhan, chaul, bhat) became the staple food and main occupation.

- Thousands of varieties were developed, including 'floating rice' for deep water.

- Land use patterns emerged: homesteads on high land, rice on middling and low lands.

Urban centers emerge. The success of rice-based agriculture supported sedentary lifestyles and, by the fifth century BCE, led to urban centers, long-distance maritime trade, and the region's first states. Sites like Wari-Bateshwar, Mahasthan, and Mainamati show evidence of complex urban life, administration, and industries like iron-smelting and bead production, often using local materials like clay for terracotta art.

3. A history defined by multiple, moving frontiers.

The history of Bangladesh is a history of frontiers.

Meeting ground of opposites. The Bengal delta has always been a meeting ground of diverse forces, and their encounters have shaped its distinct character. Several frontiers have moved across the region over millennia, influencing its social, cultural, and political development.

Key historical frontiers:

- Land-Water Frontier: The dynamic edge between land and water, moving primarily north to south as the delta builds up.

- Agrarian Frontier: The division between settled, irrigated agriculture and shifting cultivation/forest, moving eastwards as forests were cleared for farming.

- State Frontier: The boundary between areas controlled by states and those ruled by other forms of organization, gradually expanding from west to east.

- Sanskritic Frontier: The spread of Indo-European languages and Sanskritic culture from the west, interacting with pre-existing languages and worldviews.

- Religious Frontier: The encounter and intermingling of different religious traditions, notably the gradual spread and domestication of Islam from the thirteenth century onwards.

Interplay and identity. These frontiers often overlapped and influenced each other. For example, the spread of Islam in the eastern delta was linked to the agrarian frontier, as charismatic pioneers reclaimed land under state patronage. This long-term interplay created a multilayered culture where identities were complex and often combined elements from different traditions, such as the crucial hyphenation of Bengali and Muslim identities that became central to the delta's modern history.

4. The delta served as a vital global crossroads.

The Bengal delta has always had a remarkably mobile population.

Hub of connectivity. The Bengal delta has historically been integrated into extensive networks of trade, pilgrimage, and cultural exchange, serving as a gateway between the Indian Ocean world and the vast hinterlands of South, Central, and East Asia. Water transport was paramount, with numerous rivers and ports facilitating movement.

Trade routes and goods. The delta was connected by two major maritime routes: one westwards to India, Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Africa, and the Mediterranean, and another eastwards to Arakan, Burma, Southeast Asia, and China.

- Early exports: Cassia, spikenard, aloe wood, rhinoceros horn, silk, war horses, river pearls, cotton textiles (especially muslin).

- Later exports: Rice (major exporter by the sixteenth century), sugar, clarified butter, opium, indigo, tea, jute.

- Imports: Cowries (from Maldives), silver (from China/Burma), conch shells, spices, porcelain, satin.

Cosmopolitan centers. Port cities like Tamralipti, Gaur, Chittagong, and Dhaka were cosmopolitan places where merchants and travelers from diverse backgrounds met. From the sixteenth century, European traders (Portuguese, Dutch, English, French) arrived, attracted by Bengal's wealth. While they sought to control trade, local merchants largely retained dominance due to lower costs and better market knowledge. The delta's openness brought not just goods and wealth but also a constant stream of external cultural influences and new ideas.

5. British rule brought profound and lasting transformations.

European rule brought the people of Bengal economic upheaval, a social shake-up and a cultural kick in the teeth.

A new kind of rule. The British East India Company's victory at Polashi in 1757 marked the beginning of European colonial rule, distinct from previous foreign overlords like the Mughals. The British aimed not just to extract wealth but to transform Bengal's economy and society, leading to numerous experiments and policies.

Key colonial legacies:

- Permanent Settlement (1793): Transformed tax collectors (zamindars) into de facto landowners, making peasants their tenants. Fixed state tax in perpetuity, creating a buffer against environmental risks but encouraging landlord absenteeism and sub-infeudation. Denied peasants property rights.

- Export-Oriented Cash Cropping: Large-scale production of crops like opium, indigo, tea, and jute for overseas markets, transforming the agrarian economy and creating new links to global markets.

- New Institutions: Introduction of codified law (including separate personal laws by religion), English as the language of rule/elite education, modern universities (Kolkata, Dhaka), and a salaried police force.

- Urban Shift: Rise of Kolkata as the capital and economic hub, leading to the decline of older centers like Dhaka.

Social and cultural impact. Colonial rule intensified existing social hierarchies and created new ones, notably the bhodrolok elite. It also fostered the emergence of 'Hindu' and 'Muslim' as distinct political categories, leading to communal tensions. Despite resistance and hardship (like the devastating famine of 1769-70 and 1943-44), these British legacies profoundly shaped the delta's society, economy, and political landscape, enduring long after the end of colonial rule in 1947.

6. Partition in 1947 was a traumatic rupture.

In 1947, the Partition of India tore that fabric asunder.

Vivisection of Bengal. The Partition of British India in 1947, based on the 'two-nations theory' advocating a Muslim homeland (Pakistan), led to the division of Bengal. This was not a simple split but a complex vivisection into 201 pieces, including numerous enclaves, leaving many communities separated from their administrative centers and neighbors.

Creation of East Pakistan. The largest part of Bengal, along with most of Sylhet from Assam, became East Pakistan, a territory separated from West Pakistan by 1,500 km of India. This new entity, roughly coinciding with modern Bangladesh, was overwhelmingly rural and Muslim-majority, but retained a significant non-Muslim minority (one-fifth of the population).

Mass migration. Partition triggered massive population exchange, though slower and less violent than in Punjab. Hundreds of thousands migrated across the new border in both directions, often leaving behind property and facing uncertain futures.

- Hindus from East Pakistan migrated to India.

- Muslims from India (Muhajirs) migrated to East Pakistan.

- Cross-border migration continued for years, fluctuating with political events.

Enduring legacy. Partition created a new international border, a concept unfamiliar to the delta's inhabitants, and left a legacy of divided families, abandoned properties, and unresolved territorial issues. It also entrenched the political salience of religious identity, setting the stage for future conflicts within Pakistan.

7. The Pakistan experiment led to political disintegration.

Pakistan was a state administering two discrete territories, separated from each other by about 1,500 km of Indian terrain.

A unique state. Pakistan was founded on religious nationalism, governing two geographically separate wings. It inherited few central state institutions from British India, facing immediate challenges in establishing authority and forging a unified national identity. East Pakistan, though more populous, was economically disadvantaged and politically marginalized.

Language controversy. Early attempts to impose Urdu as the sole state language ignited the Language Movement (Bhasha Andolon) in East Pakistan, where Bengali was spoken by the majority. This struggle became a focal point for broader grievances regarding political representation, economic disparity, and cultural identity.

- Protests in 1952 led to police killings, creating martyrs and symbols (Shohid Minar).

- The movement highlighted the cultural divide and West Pakistani elite's condescending view of Bengali Muslims.

Political and economic disparity. East Pakistan felt increasingly treated as an internal colony, with its resources (like jute export earnings) diverted to develop West Pakistan. Economic disparities widened, fueling resentment and demands for regional autonomy. The 1954 provincial elections saw the ruling Muslim League routed by the United Front, signaling deep disillusionment.

Military rule. Political instability culminated in the 1958 military coup led by Ayub Khan. This authoritarian regime, dominated by West Pakistani (especially Punjabi) military and bureaucratic elites, further marginalized East Pakistan. Despite economic growth, inequality increased, and the regime's heavy-handed tactics and disregard for Bengali aspirations (like banning Tagore songs) intensified the autonomy movement, ultimately leading to Pakistan's violent disintegration in 1971.

8. The 1971 war birthed an independent state.

The Liberation War of 1971 was the delta’s third big shock of the twentieth century.

Operation Searchlight. Following the Awami League's landslide victory in the 1970 elections and the failure of political negotiations, the Pakistan army launched a brutal crackdown on East Pakistan on 25 March 1971. This punitive operation aimed to crush Bengali nationalism through targeted killings, particularly of students, intellectuals, and Hindus.

War of Liberation. The army's assault ignited widespread resistance. The Awami League leadership formed a government-in-exile in India and formally proclaimed the independent state of Bangladesh.

- Freedom Fighters (Mukti Bahini) organized resistance, receiving training and support from India.

- The war involved guerrilla tactics, mass displacement (millions fled to India), and atrocities committed by the Pakistan army and their local collaborators.

- The conflict drew international attention, with India supporting Bangladesh and the US/China backing Pakistan.

Indian intervention and victory. After months of conflict, India intervened militarily in December 1971, following Pakistani air strikes. Indian forces, fighting alongside the Freedom Fighters, rapidly advanced. The Pakistan army surrendered on 16 December 1971, leading to the birth of the independent state of Bangladesh. The war left a legacy of immense human cost, material destruction, and unresolved issues regarding collaborators and war victims.

9. Independent Bangladesh grappled with shaping its political system.

By the end of 1975 Bangladesh had turned its back on both Mujib’s vision and the revolutionary path.

A new republic. Born out of war, Bangladesh declared itself a 'people's republic' based on nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman returned from Pakistani captivity to lead the new state, initially establishing a parliamentary system. The immediate post-war period was marked by national jubilation but also immense challenges: war damage, displaced populations, and a weak state apparatus.

Economic and political crisis. Despite initial nationalization policies and international aid, the economy struggled, exacerbated by mismanagement and corruption. Popular disillusionment grew, culminating in the devastating famine of 1974. Political opposition mounted, leading Mujib to declare a state of emergency and establish a single-party presidential system in early 1975.

Military takeovers. This move towards civilian autocracy was short-lived. Mujib was assassinated in an army coup in August 1975, followed by further coups. Major-General Ziaur Rahman emerged as the new ruler, ushering in a period of military dictatorship (1975-1990).

- Zia's regime liberalized the economy, favoring the private sector and foreign investment.

- It also marked a return to authoritarian rule and the political exploitation of Islam, legacies from the Pakistan era.

Return to democracy. A popular uprising in 1990 ended military rule, leading to the restoration of parliamentary democracy. However, the political system remained dominated by parties born under military

[ERROR: Incomplete response]

Last updated:

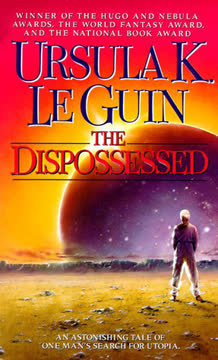

Review Summary

A History of Bangladesh receives largely positive reviews, with an average rating of 4.21/5. Readers praise its accessibility, comprehensive overview, and unbiased approach to the country's complex history. Many found it helpful for understanding Bangladesh's cultural context and modern society. The book is appreciated for its well-structured content, illustrations, and balanced perspective. Some readers note its usefulness as an introductory text for students and travelers. A few criticisms mention repetitiveness and occasional oversimplification, but overall, it's recommended for those seeking to learn about Bangladesh.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.