Key Takeaways

1. The Sudden Revelation of Undocumented Status

“The government doesn’t know we exist. We could get deported at any time.”

A mundane afternoon shattered. At nearly thirteen, Sara's world crumbled when her older sister, Samira, casually revealed they were "illegal aliens" without Social Security numbers, facing potential deportation back to Iran. This shocking truth overshadowed typical teenage worries like acne or crushes, instantly transforming her perception of herself from a normal American kid to a criminal and an "alien." The revelation was particularly jarring as her younger brother, Kia, born in the U.S., was a citizen, blissfully unaware of his sisters' precarious status.

A decade of hidden truth. The family had been living in the Bay Area for ten years, having fled Iran amidst the 1980 revolution, hostage crisis, and war. Her parents, desperate for freedom and opportunity, paid $15,000 for passports and special permission to leave, initially on visitor's visas. When these expired, they applied for political asylum, but the application mysteriously vanished, leaving them in a legal limbo that would define Sara's adolescence.

The constant shadow of fear. This newfound knowledge instilled a pervasive anxiety in Sara, a "refrain through the rest of my teen years: We. Could. Get. Deported. At. Any. Time." The fear of losing everything – friends, home, and the American life she knew – became a constant undercurrent, shaping her decisions and interactions, and making her feel fundamentally different from her law-abiding, American-born friends.

2. The Unseen Sacrifices of Immigrant Parents

My parents abandoned everything they knew and loved because they didn’t want their daughters to grow up with a strict religious code.

A life uprooted for freedom. Sara's parents, Ali and Shohreh, left behind a burgeoning Tehran, where her mother once wore miniskirts and her father dated openly, for the uncertainties of America. The Islamic Revolution brought strict dress codes, segregation, and bans on Western culture, prompting their perilous escape. They sought a life where their children could enjoy freedoms they no longer had, a testament to their profound love and foresight.

Financial and personal toll. Despite having a mechanical engineering degree, Sara's father couldn't get qualified jobs due to his undocumented status, leading them to run a small, often "thankless" luggage sales and repair business. They worked six days a week, sacrificing personal time and financial stability, even taking out an equity loan on their house for Samira's college tuition. This constant struggle to make ends meet, coupled with their own unfulfilled dreams, was a heavy burden.

The immigrant child guilt complex (ICGC). Sara and her siblings developed ICGC, a "chronic disorder" causing "constant gnawing guilt for the multitude of sacrifices their parents made." This guilt fueled their drive for good grades and success, a way to "return the favor" for their parents' immense efforts. It also meant enduring their parents' own unaddressed dental issues while ensuring their children received proper care, a stark reminder of the disparities.

3. Sibling Bonds: A Lifeline in Adolescence

No matter how regularly Samira and I brought each other to tears, my mom swore we’d grow up to realize we couldn’t live without one another.

From rivals to confidantes. Despite frequent childhood squabbles over TV remotes and Leonardo DiCaprio, Sara's mother presciently predicted that she and Samira would become best friends. This transformation began in high school when Samira, a senior, took freshman Sara under her wing, offering protection and a coveted "Little Sami" nickname. Their shared secret of undocumented status and address fraud further solidified their bond, creating an exclusive alliance against the outside world.

Unwavering loyalty and shared secrets. Sara's loyalty to Samira became paramount, surpassing even her parents' authority. She covered for Samira's illicit activities, from cutting school to drinking, understanding that her sister's social standing was more valuable than parental approval. This loyalty was tested when Samira secretly traveled to Mexico, risking deportation, but Sara's silence proved her trustworthiness, forging an unbreakable bond.

A surrogate parent and emotional anchor. Sara, as the middle child, became a surrogate mother to her much younger brother, Kia, picking him up from school, making snacks, and even bringing him to her jobs. Their bond was so deep that Kia's emotional state often mirrored Sara's, leading to dramatic outbursts when her crushes hurt her. This unique dynamic meant Sara experienced both the care of an older sibling and the responsibility of raising a younger one, shaping her into a nurturing figure.

4. Navigating Cultural Identity and Self-Perception

My whole life, my mom and aunts had praised me for how American I looked. It was a virtue to have paler skin than most Iranians, not to mention hair that was several shades lighter than my family members’.

The burden of appearance. Sara's self-esteem was constantly challenged by physical insecurities, particularly her "dominant nose" and unibrow, which she felt confirmed Iranian stereotypes. Despite her family's praise for her "American" features, a cruel comment from a crush about her "ONE eyebrow" highlighted her perceived flaws. This led to a desperate desire to conform to American beauty standards, even defying her mother's cultural rule against plucking eyebrows before age fifteen.

Contrasting cultural norms. Iranian culture, particularly among older generations, placed immense importance on appearances and family perception, often leading to judgment over "tacky dresses, botched plastic surgery, and disastrous haircuts." This pressure meant Sara's mother feared allowing her to pluck her eyebrows early, lest relatives whisper about her being a "bad mom" or her daughters being "sluts and harlots." This clash between traditional expectations and American teenage desires created internal conflict.

The struggle to fit in. Sara felt like an "ugly duckling" in high school, struggling to compete with girls who had "perfectly styled perms and brand-new boobs." Her Iranian heritage also made her feel like an "undesirable exotic race" to boys, leading her to believe her race put her at a disadvantage. This constant battle with self-perception, fueled by external judgments and cultural differences, deeply impacted her confidence and sense of belonging.

5. The Bureaucratic Labyrinth of Immigration

There was no worse feeling of defeat than waiting at the INS for five-plus hours, only to be turned away for not presenting the proper paperwork that you could have sworn you’d never even received in the mail.

A never-ending nightmare. The family's immigration journey was a "legalization nightmare" marked by "messy, arduous, and complicated attempts at becoming US citizens." After their initial asylum application vanished, they pursued "adjustment of status" through an American uncle, a process that dragged on for years, requiring endless paperwork, exorbitant legal fees, and countless frustrating visits to the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service).

"Aging out" and the race against time. A critical hurdle arose when Samira approached 21, the age at which she would "age out" of their green card application, forcing her to restart the entire process. This created immense pressure, leading to a frantic rush to get fingerprints processed and an interview date secured before her birthday. The parents' desperate plea at the INS office, banging on doors and tearfully explaining their predicament, highlighted the arbitrary and unforgiving nature of the system.

The deceptive ease of the end. After 18 years, Sara finally received her green card, a process that felt "deceptively easy" in its final hour, but only after years of "illegal immigrant fatigue." This long-awaited status brought financial relief for college tuition but also marked the beginning of another five-year wait to become a full citizen. The journey underscored the immense privilege of citizenship, a right earned through decades of struggle and sacrifice.

6. Love and Relationships: An Immigrant Twist

My mom admits that nerves were part of the equation but says her doubts and anxieties were allayed by the excitement of starting a life with my dad.

An unconventional love story. Sara's parents, Ali and Shohreh, had an "arranged marriage" after knowing each other for only two weeks in Iran. Despite this, their relationship was marked by undeniable chemistry, mutual respect, and a deep, enduring love, becoming a symbol of a happy marriage for their extended family. This challenged Sara's Westernized notions of romance, which typically began with "boy meets girl" rather than parental introductions.

A "divorce of convenience." The most shocking twist in their love story came when Sara learned her parents had secretly divorced in Reno, Nevada, in 1992. This was not due to marital strife but a desperate legal maneuver: a consultant advised it would allow Sara, her mother, and sister to apply for green cards through her grandmother, as only single individuals could apply through a parent who was a permanent resident. This "small price to pay" for legal residency deeply infuriated Sara, feeling it "tainted" their love story.

Parental guidance on sex and dating. Sara's parents, despite their traditional Iranian upbringing, held surprisingly progressive views on premarital sex, encouraging their daughters to "test-drive a few before settling down." However, their modesty and lack of open discussion about sex, coupled with their initial distress upon learning Sara was no longer a virgin, created a complex dynamic. Ultimately, her mother's wisdom, like "It’s always better to put yourself out there. Sometimes you’ll hear no, but you’ll never hear yes, either, unless you ask," became a guiding principle in Sara's own romantic life.

7. The Enduring Strength of Extended Family

We were a motley crew of immigrant kids with vastly different personalities (think the cast of The Breakfast Club), but with one common thread keeping us permanently entwined.

A displaced but united tribe. After fleeing Iran, Sara's maternal family, the Sanjideh contingent, largely settled in the Bay Area, forming a tight-knit community. Their "dangerous, abrupt, and mostly illegal" escapes meant leaving behind wealth and starting anew, but they did so "displaced together." This shared experience of immigration and cultural adjustment forged an unbreakable bond, making family the "only thing we had in California."

The patriarch and the "BAD Club." Sara's Dayee (maternal uncle) Mehrdad became the "true patriarch" of their "massive brood," actively fostering close relationships among the 19 first cousins. He organized elaborate annual gatherings, initially day trips, then weekend sleepovers, known as the "BAD Club" (Baba, Amoo, Dayee), where they created videos and cemented their unique bond. This intentional effort ensured the cousins remained "thick as thieves," even as they grew up and moved to different cities.

Cultural anchors and role models. The cousins, despite their diverse personalities, shared the unique experience of being raised by Iranian immigrants in America. They understood each other's struggles in a way their American friends couldn't, from navigating cultural expectations to dealing with the immigration system. Older cousins like Neda and Mitra served as role models, offering advice, companionship, and even introducing Sara to "vodka poppers" and her literary hero, Ethan Hawke, further solidifying their irreplaceable role in her life.

8. The Emotional Burden of Uncertainty

I didn’t care if we were supposedly nearing the end of our legalization nightmare. We were always supposedly nearing the end of our legalization nightmare.

The breaking point of frustration. The constant uncertainty and endless bureaucratic hurdles of their immigration process pushed Sara to her breaking point. She resented the "stupidly" long lines at the INS and the need to "camp out" for work permits, feeling it robbed her of a normal teenage life. This frustration culminated in a dramatic argument with her parents, where years of pent-up stress spilled over, leading her father to declare, "I hated his life."

The weight of parental sacrifice. Hearing her usually upbeat father express such despair was a "sobering realization" for Sara, forcing her to confront the immense emotional toll their immigration journey had taken on her parents. She recognized their "disappointments and regrets," and the "guilt got to me," realizing she had been an "ungrateful brat" for not fully appreciating their sacrifices. This moment marked a shift in her understanding of their shared struggle.

Homelessness and the meaning of "home." The family's financial struggles, exacerbated by immigration costs, forced them to sell their beloved house, leaving them "officially homeless" and temporarily living with relatives. This upheaval, particularly on Sara's 17th birthday, intensified her feelings of displacement and anger. However, the experience ultimately taught her that "a house doesn’t make a home without the people who live inside it," reinforcing the profound importance of family over material possessions.

9. The "Spork" Identity: Blending Two Worlds

I am a spork. I’m the combination of two worlds and cultures.

The path to citizenship. After 24 years in the U.S., Sara finally became an American citizen in 2005, a moment she approached with a mix of "elated? Indifferent? Obnoxiously patriotic?" The ceremony itself, held at a county fairground with vendors selling hot dogs and flags, felt anticlimactic. Despite her initial cynicism, yelling "Iran!" when her country was announced among the new citizens, she felt a surge of pride, recognizing the beauty of a diverse America "without walls built around its perimeter."

Balancing two identities. Even as a citizen, Sara continued to navigate the delicate balance between her American and Iranian identities. She resisted the notion that being American was "better than anything else," and sometimes felt her parents' subtle disappointment when she adopted American habits, like eating rice with a fork. This constant negotiation meant she would "always seem too Iranian for some and too American for others."

Embracing a unique blend. Ultimately, Sara embraces her "spork" identity – a combination of two cultures that may not fit neatly into traditional compartments. Her Iranian nose, once a source of insecurity, becomes a symbol of her heritage, a feature she chooses not to alter. This acceptance signifies a journey from self-consciousness and the fear of not belonging to a proud acknowledgment of her unique, blended self, shaped by both her roots and her adopted country.

10. A Call to Action: Understanding the Immigrant Experience

For undocumented immigrants, past or present, the fear becomes a normal part of our daily lives.

The enduring fear. Sara emphasizes that the fear of deportation is a "normal part" of life for undocumented immigrants, a feeling that persists even after gaining legal status. She acknowledges the current political climate makes this fear even more acute, contrasting it with the Reagan era when amnesty was granted to millions. This highlights the unpredictable and often arbitrary nature of immigration policies.

Rights and resilience. Despite the challenges, Sara offers words of advice to undocumented individuals: avoid criminal records, never sign paperwork you don't understand, and never open the door to immigration officers without a warrant. She stresses that "being afraid does not have to mean giving into intimidation tactics," empowering readers with basic defensive strategies.

Solidarity and hope. The author concludes with a powerful message of solidarity, recalling the Women's March and airport protests against the Muslim ban. These moments reminded her that "none of us are alone in this." She encourages readers to find hope in the millions of activists fighting on behalf of marginalized groups, reinforcing the idea that collective action and empathy are crucial in a world where the future of immigration remains uncertain.

Last updated:

Review Summary

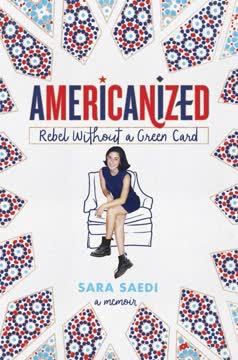

Americanized receives mostly positive reviews, praised for its humor, relatability, and insights into Iranian culture and the immigrant experience. Readers appreciate Saedi's candid storytelling and the book's educational value regarding immigration processes. Some critics find certain sections repetitive or less engaging, particularly those focused on typical teenage concerns. The memoir resonates strongly with Iranian-Americans and immigrants, while also appealing to a broader audience interested in diverse perspectives. Overall, it's considered an important, timely work that humanizes the immigrant experience.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.