Key Takeaways

1. The Prophet Muhammad and the Foundation of the Ummah

Social justice was, therefore, the crucial virtue of Islam.

A transformative vision. In 7th century Arabia, Muhammad received revelations forming the Quran, addressing the social crisis in Mecca where traditional tribal values of caring for the weak were eroding due to mercantile wealth. His message wasn't new doctrine about God, but a call for Arabs to return to the primordial faith of Abraham, emphasizing justice, equity, and compassion for all members of society. The Quran insisted on sharing wealth and creating a community (ummah) based on submission (islam) to God's will, not blood ties.

Building a new community. Facing persecution in Mecca, Muhammad and his followers migrated to Yathrib (Medina) in 622 CE (the Hijrah), marking the start of the Muslim era. Here, Muhammad established a revolutionary "supertribe" bound by shared ideology, not kinship, uniting previously warring factions, including Muslims, pagans, and Jews, under a single compact. The mosque served as a community center for all aspects of life, reflecting the Islamic ideal of integrating the sacred and profane, aiming for tawhid (unity) in society.

Peace through struggle. The early Medinan community faced existential threats from Mecca and internal dissent. Muhammad's leadership, including strategic military actions like the Battle of Badr and the Battle of the Trench, secured the ummah's survival. His eventual peaceful takeover of Mecca in 630 CE, cleansing the Kabah and integrating pagan rites into the hajj, culminated in the unification of Arabia under Islam, ending centuries of tribal warfare and establishing peace.

2. The Rashidun Caliphs and Rapid Conquest

Where Christians discerned God’s hand in apparent failure and defeat, when Jesus died on the cross, Muslims experienced political success as sacramental and as a revelation of the divine presence in their lives.

Succession and unity. Upon Muhammad's death in 632 CE, the nascent ummah faced the challenge of leadership. Abu Bakr was elected the first khalifah (deputy), prioritizing the unity of the community against tribal revolts (riddah wars). His success solidified the idea of a single Muslim polity, though debates about succession, particularly the claims of Ali, sowed seeds for future divisions.

Explosive expansion. Under the second caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab, the need to channel the Arabs' raiding energies and maintain the ummah's unity led to campaigns against the Byzantine and Sassanid empires. These pragmatic ghazu raids, not religious wars of conversion, resulted in astonishing victories, conquering Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and Persia within two decades. This rapid expansion was facilitated by the exhaustion of the two empires and local populations alienated by their rulers.

A new world order. The conquests created a vast empire, seen by Muslims as a sign of God's favor and validation of the Quranic promise of prosperity for a just society. Umar established garrison towns (amsar) to house the Arab soldiers, keeping them separate from the conquered populations and preserving their Arab identity. Non-Muslims (dhimmis) were protected, allowed religious freedom, and paid a poll tax, reflecting the Quran's respect for "People of the Book" and the Arab tradition of protecting clients.

3. The First Civil War (Fitnah) and its Enduring Divisions

The murder of the man who had been the first male convert to Islam and was the Prophet’s closest male relative was rightly seen as a disgraceful event, which posed grave questions about the moral integrity of the ummah.

Crisis of leadership. The assassination of the third caliph, Uthman, in 656 CE, by disgruntled soldiers, plunged the ummah into its first major civil war (fitnah), a period of profound temptation and testing. Ali ibn Abi Talib was acclaimed caliph, but his inability to punish Uthman's murderers alienated powerful factions, including Aisha and the Umayyad family led by Muawiyyah.

Conflict and compromise. The conflict escalated, leading to battles like the Battle of the Camel and the inconclusive Battle of Siffin. Attempts at arbitration failed, deepening the rift. Muawiyyah, based in Syria, challenged Ali's authority, eventually leading to Ali's assassination by a Kharajite extremist in 661 CE. Ali's son Hasan briefly claimed the caliphate but ceded it to Muawiyyah for peace.

Seeds of sectarianism. The fitnah was devastating, highlighting the fragility of the ummah's unity. It led to the emergence of distinct factions:

- Shiiah i-Ali (Partisans of Ali): Believed leadership belonged to Ali's descendants, who inherited special spiritual authority (ilm).

- Kharajites (Seceders): Believed the caliph should be the most pious Muslim, condemning both Ali and Muawiyyah for perceived injustices.

- Sunnis: Those who sought unity and accepted Muawiyyah's rule for the sake of peace, later developing the concept of following the Prophet's sunnah (customary practice) as preserved by the community.

This period became a foundational narrative for understanding justice, authority, and the moral state of the community.

4. The Umayyads: Centralization and Second Fitnah

Abd al-Malik (685-705) was able to reassert Umayyad rule, and the last twelve years of his reign were peaceful and prosperous.

Restoring order. Muawiyyah established the Umayyad dynasty with its capital in Damascus, bringing stability after the first fitnah. He ruled like an Arab chief, maintaining the segregation of Arab Muslims in garrison towns and discouraging conversion to preserve the elite status and tax base. The empire continued to expand, reaching North Africa and parts of Central Asia.

Dynastic struggles. Muawiyyah's decision to appoint his son Yazid I as successor sparked the second fitnah (680-692). This period saw the tragic death of Husain, Ali's son, at Kerbala, a pivotal event for Shiis. Abdallah ibn al-Zubayr led a revolt in the Hijaz, challenging Umayyad legitimacy and advocating a return to the ideals of the first ummah.

Consolidation and identity. Abd al-Malik eventually suppressed the revolts, centralizing the empire and asserting a distinct Islamic identity. Arabic became the official language, Islamic coinage was introduced, and the Dome of the Rock was built in Jerusalem as a powerful symbol of Islam's presence and supremacy. While the Umayyads brought political stability and administrative efficiency, their increasingly autocratic rule and perceived worldliness fueled discontent among pious Muslims who yearned for a more authentically Islamic society.

5. The Rise of Islamic Piety and Religious Law (Shariah)

The political health of the ummah was, therefore, central to the emerging piety of Islam.

Questioning the state. The civil wars and the perceived shortcomings of the Umayyad state spurred a religious movement. Concerned Muslims, including Quran reciters and ascetics, debated what it truly meant to be Muslim and how society should reflect God's will. This intellectual ferment, rooted in political dissatisfaction, played a role similar to Christological debates in Christianity, shaping core Islamic concepts.

Developing jurisprudence. Jurists (faqihs) began systematizing Islamic law (fiqh) to guide Muslims in living according to Quranic principles. Facing limited explicit legislation in the Quran, they collected reports (ahadith) about the Prophet's life and relied on the customary practice (sunnah) of early Muslim communities. Scholars like Abu Hanifah and later al-Shafii developed methodologies for legal reasoning (ijtihad, qiyas) and established schools of law (madhhabs).

A counter-culture emerges. The Shariah, as the body of Islamic law came to be known, became more than just a legal system; it was an attempt to build a counter-culture based on the egalitarian and just ideals of the Quran, implicitly criticizing the aristocratic Umayyad court. By imitating the Prophet's sunnah in daily life, Muslims sought to internalize his perfect surrender to God, making the Shariah a path to interior spirituality and a means of experiencing the divine presence in mundane actions.

6. The Abbasid Empire: Autocracy and Cultural Zenith

By the time of Caliph Harun al-Rashid (786-809), the transformation was complete.

Shifting power. The Abbasids, capitalizing on widespread discontent with the Umayyads, particularly among non-Arab converts (mawalis) and some Shiis, seized power in 750 CE. Despite initial Shii support, they quickly established an absolute monarchy, moving the capital to Baghdad, modeled on Persian imperial traditions, and distancing themselves from the egalitarian ethos of the early ummah.

Imperial splendor and tension. The Abbasid court, especially under Harun al-Rashid, reached a peak of luxury and cultural achievement, fostering a renaissance in science, philosophy (Falsafah), and arts, drawing on Hellenistic and Persian learning. However, this autocratic style, with the caliph as "Shadow of God on earth," clashed with Islamic ideals and alienated the pious. The religious movement, particularly the ahl al-hadith, grew in influence, emphasizing tradition and criticizing the court's worldliness.

Consolidating Sunni Islam. While the caliphate became increasingly secular in practice, the Abbasids patronized the ulama and the development of Shariah, which became the law governing the lives of ordinary Muslims. This period saw the formalization of the four Sunni law schools and the emergence of Asharism as a dominant theological school, reconciling rationalism and tradition. The political decline of the caliphate from the mid-9th century onwards coincided with the consolidation of Sunni Islam as the faith of the majority, emphasizing community unity over political dissent.

7. Esoteric Islam: Shiism, Philosophy (Falsafah), and Mysticism (Sufism)

The esoterics did not think that their ideas were heretical.

Beyond the surface. Alongside mainstream Sunni Islam, several esoteric movements developed, appealing to intellectual or mystically inclined elites who sought deeper meanings in the faith. These groups often practiced secrecy (taqiyyah) due to political persecution or the belief that their insights were not for the masses. They adhered to the core practices of Islam but interpreted them through different lenses.

Diverse paths to truth.

- Shiism: After the Kerbala tragedy, Twelver Shiism, guided by the imams (descendants of Ali), developed a mystical focus on the hidden (batin) meaning of the Quran and the concept of the Hidden Imam, who would return as the Mahdi. Ismailis (Seveners) also sought esoteric knowledge but were often politically active, establishing rival caliphates.

- Falsafah: Muslim philosophers (Faylasufs) integrated Greek rationalism with Islam, seeing reason as a path to divine truth and viewing revealed religion as a symbolic expression of philosophical concepts accessible to the masses. Figures like al-Kindi, al-Farabi, and Ibn Sina sought to reconcile faith and reason.

- Sufism: Islamic mysticism (Sufism) sought direct experience of God through asceticism, contemplation, and practices like dhikr. Originating as a reaction against worldliness, Sufism aimed to reproduce the Prophet's interior state of surrender, emphasizing love and the potential for human beings to experience divine presence. Early figures like Rabiah and al-Bistami explored ecstatic states, while Junayd of Baghdad advocated a more "sober" path.

Enriching the tradition. These esoteric schools, though sometimes viewed with suspicion by the ulama, enriched Islamic thought and spirituality. They explored dimensions of faith beyond legal and theological debates, contributing to a more profound and multifaceted understanding of God, the Quran, and the human condition, demonstrating Islam's capacity for creative adaptation.

8. Decentralization and a New Islamic Order (935-1258)

It seems that once the caliphate had been—for all practical purposes—abandoned, Islam got a new lease of life.

End of central authority. By the 10th century, the Abbasid caliphate had lost effective political control, with various regional dynasties and military commanders (amirs) establishing independent states across the vast Islamic world. While the caliph remained a symbolic figurehead, real power fragmented, leading to political instability and shifting frontiers.

Flourishing regional cultures. Paradoxically, this political decentralization coincided with a cultural and religious florescence. Instead of one center, multiple vibrant capitals emerged (Cairo, Cordova, Samarkand), fostering intellectual and artistic creativity. Philosophy, literature, and science thrived in these courts, often blending Islamic thought with local traditions.

The rise of the ulama and Sufism. In the absence of strong central government, the ulama and Sufi masters became crucial in providing cohesion and identity. The development of madrasahs standardized religious education and gave the ulama a distinct power base, enabling them to administer the Shariah at the local level. Sufism transformed into a popular mass movement, with tariqahs (orders) providing spiritual guidance and social networks across regions, deepening the piety of ordinary Muslims and creating a shared, international Islamic culture independent of the ephemeral states.

9. The Mongol Catastrophe and its Transformative Aftermath

Appalling as the Mongol scourge had been, the Mongol rulers were fascinating to their Muslim subjects.

Unprecedented destruction. In the 13th century, the Mongol invasions under Genghis Khan and Hulegu devastated the heartlands of the Islamic world, destroying cities like Bukhara and Baghdad (ending the Abbasid caliphate in 1258), massacring populations, and disrupting established political and cultural centers. This was a traumatic shock, seen by many as the end of the world they knew.

Adaptation and conversion. Despite the initial brutality, the Mongol empires eventually stabilized. Unlike previous invaders, they brought no competing spirituality but were tolerant of all religions. By the late 13th and early 14th centuries, the Mongol rulers in Persia, Central Asia, and the Golden Horde converted to Islam, becoming the new dominant Muslim powers.

Enduring influence and new directions. The Mongol states, run on military lines with a focus on dynastic power (Yasa law code), represented a continuation of the militarization seen under the later Abbasids and Seljuks, but with greater intensity. This era saw:

- The formal closing of the "gates of ijtihad" in Sunni Islam, emphasizing conformity to past legal rulings.

- A conservative reaction among some ulama, suspicious of foreign influence.

- A profound mystical response, exemplified by Jalal al-Din Rumi, whose Sufi poetry expressed cosmic homelessness and boundless spiritual potential, helping Muslims process the trauma and find new meaning.

- The rise of reformers like Ibn Taymiyyah, who advocated a return to fundamentals and challenged established legal and theological norms.

10. The Gunpowder Empires: Safavids, Moghuls, Ottomans

Three major Islamic empires were created in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries: the Safavid Empire in Iran, the Moghul Empire in India and the Ottoman Empire in Anatolia, Syria, North Africa and Arabia.

New imperial scale. The development and use of gunpowder weapons in the 15th century enabled rulers to establish larger, more centralized empires than previously possible in the agrarian world. Building on Mongol precedents of military states, these empires integrated civilian administration and adopted distinct Islamic orientations, unlike the earlier Abbasids.

Sectarian and pluralistic models.

- Safavid Empire (Iran): Founded by Shah Ismail, it imposed Twelver Shiism as the state religion, leading to a decisive and often violent split with Sunnism. Later shahs, like Abbas I, consolidated a more orthodox Shiism, patronizing ulama and fostering a cultural renaissance, though some ulama became increasingly literalist and intolerant.

- Moghul Empire (India): Founded by Babur, it ruled a predominantly non-Muslim population. Emperor Akbar pursued a policy of religious pluralism and tolerance (sulh-e kull), integrating Hindus into the administration and fostering a unique Indo-Islamic culture, though later emperors like Aurengzebe adopted more sectarian policies, contributing to the empire's decline.

- Ottoman Empire (Anatolia, Middle East, North Africa, Balkans): The most enduring, it established a vast, well-administered state with Istanbul as its capital. Under Suleiman the Magnificent, the Shariah was formalized as state law, creating a partnership between the sultan and the ulama, though this eventually led to the ulama's dependence on the state and resistance to change.

Zenith and inherent limits. These empires represented a peak of Islamic political and cultural power, expanding into new territories like Eastern Europe and India. However, as agrarian states, they eventually faced economic and administrative limitations. Their internal dynamics, including sectarianism (Safavids, Ottomans) or the challenge of ruling diverse populations (Moghuls), and the growing conservatism of state-sponsored religious institutions, set the stage for future challenges.

11. The Arrival of the West and the Trauma of Colonialism

The Islamic world has been convulsed by the modernization process.

A new global power. From the late 18th century, the Islamic world, whose great empires were in decline due to the inherent limitations of agrarian economies, encountered a fundamentally new type of civilization emerging from Western Europe. Based on industrialization, scientific innovation, and continuous expansion, the West possessed an unprecedented capacity for wealth generation and military power.

Invasive modernization. Western powers began colonizing Islamic lands, not just for resources but to integrate them into their commercial and industrial network. This imposed rapid, often brutal modernization, transforming economies, legal systems, and urban landscapes. Unlike the West's gradual, internally driven modernization, this process was externally controlled, creating dependent economies and societies divided between a Western-educated elite and a traditional majority.

Humiliation and dislocation. The experience of being colonized by a previously "backward" region was deeply humiliating for Muslims, challenging their historical understanding of Islam's success as a sign of divine favor. Colonial rule often involved the marginalization or suppression of Islamic institutions and law, leading to a profound sense of dislocation and loss of identity. Muslims felt they were losing control of their destiny, a crisis that went beyond politics and touched the core of their religious identity, prompting a search for how to respond to this unprecedented challenge.

12. Modern Challenges: Statehood, Secularism, and Fundamentalism

The struggle for a modern Islamic state is the Muslim equivalent of this dilemma.

The quest for a modern polity. The colonial encounter forced Muslims to confront the need to create modern states. Unlike Christianity, where politics was less central, the health of the ummah and the implementation of divine justice in society were core Islamic concerns. Finding a form of government compatible with both Islamic ideals and modern realities proved challenging.

Secularism and its discontents. Western secularism, often imposed aggressively by colonial powers or post-colonial regimes (like Atatiirk or the Pahlavis), was frequently seen not as a neutral separation but as an attack on religion. This coercive secularism alienated many Muslims and fueled resistance. Attempts to graft Western democracy onto Islamic concepts like shurah (consultation) faced difficulties due to historical context and the perception of Western hypocrisy in supporting authoritarian regimes.

Fundamentalism as a response. Disappointment with secular nationalism and the trauma of modernity contributed to the rise of fundamentalism from the late 20th century. This global phenomenon, present in all major faiths, represents an embattled reaction against perceived threats to religious identity and values. Muslim fundamentalism

[ERROR: Incomplete response]

Last updated:

FAQ

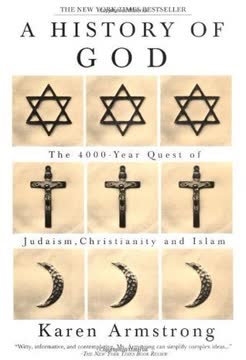

1. What is "Islam: A Short History" by Karen Armstrong about?

- Comprehensive overview: The book provides a concise yet thorough history of Islam, from its origins in 7th-century Arabia to the modern era.

- Focus on context: Armstrong emphasizes the interplay between spiritual ideals and political realities in Islamic history.

- Key themes: The narrative explores the development of Islamic beliefs, practices, sects, and the impact of external forces such as colonialism and modernity.

- Purpose: The book aims to demystify Islam for Western readers and correct common misconceptions.

2. Why should I read "Islam: A Short History" by Karen Armstrong?

- Accessible introduction: The book is ideal for readers seeking a clear, unbiased introduction to Islamic history and thought.

- Bridges misunderstandings: Armstrong addresses and clarifies widespread Western misunderstandings about Islam.

- Context for current events: Understanding the historical roots of contemporary issues in the Muslim world is a key benefit.

- Balanced perspective: The author presents both the spiritual and political dimensions of Islam, showing their interdependence.

3. What are the key takeaways from "Islam: A Short History" by Karen Armstrong?

- History and spirituality intertwined: In Islam, political and social life are deeply connected to religious ideals.

- Diversity within Islam: The book highlights the rich diversity of Islamic thought, practice, and sects, especially the Sunni-Shii split.

- Misconceptions addressed: Armstrong dispels myths about Islam being inherently violent or intolerant.

- Modern challenges: The book explains how colonialism, modernization, and Western influence have shaped contemporary Islamic societies and movements.

4. How does Karen Armstrong define the historical mission and core duty of Muslims in "Islam: A Short History"?

- Redemption of history: Armstrong argues that Islam’s historical mission is to create a just society where all, especially the vulnerable, are treated with respect.

- Community focus: The Quran commands Muslims to build an ummah (community) characterized by justice, equity, and compassion.

- Salvation as social order: Unlike some religions, Islamic salvation is seen as the realization of a just society, not just individual redemption.

- Integration of faith and politics: Political engagement and social justice are not distractions from spirituality but essential to Islamic religious life.

5. What are the Five Pillars of Islam, and how does "Islam: A Short History" explain their significance?

- Shahadah (Faith): Declaration of faith in one God and Muhammad as his prophet.

- Salat (Prayer): Ritual prayer performed five times daily, emphasizing submission and humility.

- Zakat (Almsgiving): Mandatory charity to support the poor, reinforcing social justice.

- Sawm (Fasting): Observance of Ramadan through fasting, fostering empathy for the less fortunate.

- Hajj (Pilgrimage): Pilgrimage to Mecca, symbolizing unity and equality among Muslims.

- Emphasis on practice: Armstrong notes that Islam prioritizes right living and community over abstract belief.

6. How does "Islam: A Short History" describe Islam’s relationship with other religions and its approach to religious diversity?

- Continuity of revelation: Islam sees itself as the continuation of the monotheistic tradition, respecting previous prophets like Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.

- People of the Book: Jews and Christians are recognized as recipients of earlier revelations and are called ahl al-kitab.

- No forced conversion: The Quran explicitly forbids coercion in matters of faith.

- Historical tolerance: Non-Muslim subjects (dhimmis) were generally allowed religious freedom and autonomy within the Islamic empires.

7. What is the significance of the Sunni-Shii split in "Islam: A Short History," and how did it originate?

- Origins in succession: The split began over disagreement about who should lead the Muslim community after Muhammad’s death—Ali (Shii view) or elected caliphs (Sunni view).

- Political and spiritual dimensions: While initially political, the division developed distinct theological and spiritual traditions.

- Impact on history: The Sunni-Shii divide has shaped Islamic history, politics, and identity, leading to different practices and interpretations.

- Modern relevance: Armstrong explains how this split continues to influence contemporary Muslim societies and conflicts.

8. How does "Islam: A Short History" address the concept of jihad and its significance in Islam?

- Primary meaning: Jihad primarily means "struggle" or "effort," often referring to the internal struggle for self-improvement and social justice.

- Defensive warfare: The Quran permits armed struggle only in self-defense or to protect the community, not for forced conversion.

- Historical context: Armstrong emphasizes that Muhammad’s military actions were shaped by the harsh realities of 7th-century Arabia.

- Modern interpretations: The book discusses how some modern fundamentalists have redefined jihad in more militant terms, often distorting its original meaning.

9. What are the roots and characteristics of Islamic fundamentalism according to "Islam: A Short History"?

- Modern phenomenon: Fundamentalism is a reaction to the challenges of modernity, colonialism, and Western dominance.

- Not unique to Islam: Armstrong notes that fundamentalism exists in all major faiths as a response to perceived threats from secularism.

- Defensive and reactionary: Islamic fundamentalists seek to return to what they see as the pure, original Islam, often in opposition to both Western influence and secular Muslim governments.

- Distortion of tradition: The book argues that fundamentalism often exaggerates or misinterprets traditional Islamic teachings, especially regarding violence and governance.

10. How does "Islam: A Short History" explain the challenges faced by modern Islamic nation-states?

- Colonial legacy: Many Muslim countries were shaped by arbitrary borders and institutions imposed by colonial powers.

- Struggle with secularism: Secularism was often imposed aggressively, leading to alienation and backlash among religious populations.

- Difficulty with democracy: Western-style democracy has often been undermined by foreign intervention or local elites, making it hard to establish stable, representative governments.

- Identity crisis: Modern Muslim states grapple with balancing Islamic values, national identity, and the demands of modernity.

11. What are the most common Western misconceptions about Islam, as discussed in "Islam: A Short History"?

- Violence and intolerance: The belief that Islam is inherently violent or intolerant is a persistent myth, often rooted in historical conflicts like the Crusades.

- Monolithic faith: Many assume Islam is uniform, ignoring its internal diversity and debates.

- Role of women: Westerners often misunderstand the status of women in Islam, not recognizing the historical and cultural complexities.

- Resistance to modernity: The idea that Islam is incompatible with modern values is challenged by Armstrong, who shows that Muslims have engaged with modernity in diverse ways.

12. What are the best quotes from "Islam: A Short History" by Karen Armstrong, and what do they mean?

- "In Islam, Muslims have looked for God in history." This highlights the centrality of social and political life in Islamic spirituality.

- "There shall be no coercion in matters of faith." Quoting the Quran, Armstrong underscores Islam’s foundational principle of religious freedom.

- "The struggle to achieve [justice] was for centuries the mainspring of Islamic spirituality." This reflects the book’s theme that social justice is at the heart of Islamic faith.

- "Fundamentalism is an essential part of the modern scene." Armstrong situates Islamic fundamentalism within a global, modern context, not as a uniquely Islamic phenomenon.

- "Religion, like any other human activity, is often abused, but at its best it helps human beings to cultivate a sense of the sacred inviolability of each individual." This quote encapsulates Armstrong’s balanced, humanistic approach to understanding Islam and religion in general.

Review Summary

Islam: A Short History receives mixed reviews. Many praise Armstrong's accessible writing and balanced perspective on Islamic history. Critics argue she is too apologetic and oversimplifies complex issues. Readers appreciate the concise overview but some find it lacking depth. The book is commended for addressing Western misconceptions about Islam, though some feel it is biased in favor of the religion. Overall, it is considered a good introduction to Islam for non-Muslims, albeit with limitations in its brevity and potential biases.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.