Key Takeaways

1. Beauty is a Constructed and Conflicting Narrative

At your birth, my mother begins, the doctor picked you up and said, “Look how big she is! She’s beautiful!” And it was true.

Early conditioning. From a young age, the author was conditioned to value beauty as a primary source of worth and validation. This was reinforced by her mother's stories of her own beauty and the attention it garnered, creating a complex dynamic where beauty was both a source of pride and a burden.

- The author's mother often compared her beauty to others, including her own, creating a sense of competition and self-doubt.

- The author's grandfather dismissed her mother's beauty as something she did not earn, further complicating the narrative.

- This early conditioning led the author to believe that her beauty was a gift, but also something she had to constantly maintain and prove.

Internalized standards. The author's perception of beauty was shaped by external validation and comparisons, leading to a constant self-evaluation. She sought validation through social media, obsessively checking likes and comments, and comparing herself to other women.

- She struggled with the idea that her beauty was a commodity, something that could be bought and sold.

- She internalized the idea that her beauty was a way to be exceptional and to earn her parents' love.

- This constant self-evaluation led to feelings of inadequacy and a need to control her image.

Conflicting messages. The author received conflicting messages about her body and sexuality, leading to confusion and shame. She was praised for her beauty but also shamed for being "too sexy," creating a sense of internal conflict.

- Her father's suggestion to "dress differently" and her cousin's fear of her being alone with a male friend highlighted the contradictory expectations placed on young women.

- She was taught to be proud of her appearance but also to be wary of the male gaze, creating a sense of unease and self-consciousness.

- This constant negotiation of conflicting messages shaped her understanding of beauty and her place in the world.

2. The Male Gaze and Female Objectification

You painted this naked woman because you found her pleasing to look at, you put a mirror in her hand, and you titled the painting Vanity to morally condemn this woman whose nakedness you had represented only for your own pleasure.

The male gaze. The author explores how women are often viewed through the lens of male desire, reducing them to objects of visual consumption. This "male gaze" shapes how women perceive themselves and their bodies.

- The author's experience in the "Blurred Lines" music video highlighted how women are often objectified and commodified for male pleasure.

- She realized that her influence and status were largely due to her appeal to men, not her own inherent worth.

- This realization led to a sense of diminishment and a feeling of being "chosified."

Commodification of the female body. The author discusses how her body became a commodity, something she could capitalize on for fame and fortune. This commodification, however, came at the cost of her own sense of self.

- She was paid for her appearance, for her ability to fill a bra or pose suggestively.

- She felt pressured to conform to certain beauty standards to maintain her marketability.

- This commodification led to a sense of alienation from her own body and a feeling of being reduced to a mere object.

Limited agency. The author acknowledges that her power and autonomy were limited by the patriarchal structures that valued her beauty only through the male gaze. She realized that her success was contingent on pleasing men, not on her own terms.

- She felt that her choices were not truly her own, but rather dictated by the expectations of a male-dominated world.

- She recognized that her autonomy was not genuine emancipation, but rather a form of self-commodification.

- This realization led to a desire to reclaim her agency and redefine her own sense of self.

3. Navigating Sexuality and Empowerment

For me, the problem wasn’t the sexualization of girls, as feminists and antifeminists would have us believe; the problem was shaming them for it.

Conflicting views on sexuality. The author grapples with the complex relationship between sexuality and empowerment, challenging the traditional feminist view that sexual expression is inherently disempowering. She argues that the problem is not sexualization itself, but the shame and judgment that often accompany it.

- She felt that being shamed for her sexuality was more damaging than the sexualization itself.

- She questioned why women should have to adapt and hide their bodies, rather than embracing them.

- This perspective challenged the binary of sexualization as either empowering or disempowering, suggesting a more nuanced approach.

Reclaiming agency through choice. The author initially believed that she was reclaiming her power by choosing to capitalize on her sexuality. She argued that feminism was about choice and that she was choosing to be sexual on her own terms.

- She felt that she was in control of her body and her image, and that this was a form of empowerment.

- She believed that she was defying societal expectations by embracing her sexuality.

- This perspective, however, was later challenged as she realized the limitations of her agency within a patriarchal system.

The limits of self-commodification. The author eventually recognized that her initial understanding of empowerment was flawed. She realized that capitalizing on her sexuality within a patriarchal system did not lead to true emancipation.

- She acknowledged that her choices were still limited by the male gaze and the commodification of female bodies.

- She recognized that her power was contingent on pleasing men, not on her own terms.

- This realization led to a desire to redefine empowerment and to find a more authentic sense of self.

4. The Price of the "Sexy" Image

By many aspects, capitalizing on my sexuality has brought me undeniable rewards.

Material success. The author acknowledges the material rewards that came with her "sexy" image, including fame, fans, and financial success. She was able to earn more money than her parents ever dreamed of, and she built a platform by sharing images of her body online.

- She gained global recognition and amassed millions of fans.

- She earned significant income through advertising and fashion campaigns.

- She was able to provide financial support to her parents.

Emotional cost. Despite the material success, the author also experienced a significant emotional cost. She felt diminished, objectified, and trapped by her sex symbol status.

- She felt that she had capitalized on her body within a system that valued beauty only through the male gaze.

- She realized that her influence was contingent on pleasing men, not on her own inherent worth.

- This led to feelings of alienation, self-doubt, and a sense of being reduced to a mere object.

Loss of control. The author felt a loss of control over her own image and narrative. She was constantly being commented on and dissected, and she felt that her identity was being defined by others.

- She was pigeonholed as a sex symbol, limiting her opportunities and her ability to express other aspects of her personality.

- She felt that her body had become a public commodity, something that was no longer entirely her own.

- This loss of control led to a desire to reclaim her agency and to redefine her own sense of self.

5. Trauma, Vulnerability, and Self-Discovery

I was fourteen the first time Owen took me by force.

Early experiences of violation. The author recounts her early experiences of sexual coercion and violation, highlighting the impact of these events on her sense of self and her relationships. She describes how she was groomed and manipulated by an older boy, Owen, and how these experiences shaped her understanding of sex and power.

- She was pressured into sexual situations and felt unable to say no.

- She experienced a sense of shame and guilt, and she struggled to understand what had happened to her.

- These early experiences of violation left her feeling vulnerable and insecure.

The impact of silence. The author explores the impact of silence and shame on her ability to process her trauma. She felt unable to talk about her experiences, and she internalized the idea that she was somehow to blame.

- She kept her experiences secret from her parents and friends, fearing judgment and rejection.

- She struggled to reconcile her experiences with her desire to be seen as strong and independent.

- This silence perpetuated her trauma and made it more difficult to heal.

Confronting the past. The author eventually began to confront her past, recognizing the impact of her early experiences on her present life. She realized that she had been carrying a burden of shame and guilt, and she began to seek healing and self-discovery.

- She started to question the narratives she had internalized about her body and sexuality.

- She began to explore her feelings of vulnerability and to reclaim her agency.

- This process of self-discovery led to a more nuanced understanding of her own experiences and her place in the world.

6. Reclaiming Agency and Redefining Self

This autonomy, I am only now conquering, after writing this book and giving voice to what I have thought and lived.

Challenging the narrative. The author actively challenges the narratives that have been imposed on her, both by society and by herself. She questions the idea that her worth is tied to her beauty and her appeal to men.

- She begins to deconstruct the idea of the "sexy" image and to explore other aspects of her identity.

- She challenges the notion that women must be either empowered or disempowered by their sexuality, seeking a more nuanced understanding.

- This process of challenging the narrative is a crucial step in reclaiming her agency.

Finding her voice. The author uses her writing as a way to give voice to her experiences and to explore her own thoughts and feelings. She recognizes that her silence has been a form of self-oppression, and she seeks to break free from it.

- She uses her writing to confront painful truths and to challenge her own beliefs.

- She explores the complexities of her relationships and her own internal conflicts.

- This process of finding her voice is a crucial step in redefining her sense of self.

Redefining empowerment. The author redefines empowerment as something that comes from within, not from external validation or male approval. She seeks to create her own narrative and to live on her own terms.

- She recognizes that true empowerment comes from self-acceptance and self-love.

- She seeks to create a life that is authentic and meaningful, not just one that is pleasing to others.

- This process of redefining empowerment is a crucial step in reclaiming her agency and creating a more fulfilling life.

7. The Complexities of Female Relationships

They’re only jealous, Mom!

Competition and comparison. The author explores the complex dynamics of female relationships, highlighting the ways in which women are often pitted against each other. She recognizes that she was taught to compete with other women for male attention and validation.

- She was conditioned to see other women as rivals, rather than allies.

- She internalized the idea that her worth was contingent on being "better" than other women.

- This competitive dynamic created a sense of unease and insecurity in her relationships with other women.

The search for connection. Despite the competitive dynamics, the author also seeks connection and solidarity with other women. She recognizes that she has often been isolated and that she longs for genuine female friendships.

- She seeks to understand the experiences of other women and to find common ground.

- She recognizes that women are often subjected to similar pressures and expectations.

- This desire for connection leads her to question the competitive narratives she has internalized.

Challenging internalized misogyny. The author confronts her own internalized misogyny, recognizing that she has often judged other women based on their appearance and their perceived appeal to men. She begins to question the ways in which she has participated in the objectification of other women.

- She recognizes that she has often been complicit in the patriarchal system that oppresses women.

- She seeks to break free from these patterns of judgment and to create more supportive and empowering relationships with other women.

- This process of challenging her own internalized misogyny is a crucial step in her journey of self-discovery.

8. Transactions, Power, and Self-Worth

I was there to work.

The transactional nature of relationships. The author explores the transactional nature of many of her relationships, particularly those in the entertainment industry. She recognizes that she was often treated as a commodity, and that her worth was often measured by her ability to provide something to others.

- She was paid to attend events, to pose for photos, and to provide a certain image.

- She felt that her relationships were often based on what she could offer, rather than on genuine connection.

- This transactional dynamic led to a sense of alienation and a feeling of being used.

Power dynamics. The author examines the power dynamics that were often at play in her relationships, particularly with men. She recognizes that she was often in a position of vulnerability, and that her power was often limited by the expectations of others.

- She was often subjected to unwanted attention and objectification.

- She felt that she had to constantly negotiate her own boundaries and desires.

- This awareness of power dynamics led to a desire to reclaim her agency and to redefine her own sense of self.

Redefining self-worth. The author seeks to redefine her self-worth as something that is not contingent on external validation or transactional relationships. She recognizes that her value is inherent, not something that can be bought or sold.

- She begins to prioritize her own needs and desires, rather than seeking approval from others.

- She seeks to create relationships that are based on mutual respect and genuine connection.

- This process of redefining her self-worth is a crucial step in her journey of self-discovery.

9. The Search for Authenticity and Control

I was on the defensive—I wanted to protect the atmosphere she had tried to create on set and the other young women who might have become friends.

The desire for authenticity. The author expresses a deep desire for authenticity, a longing to be seen and accepted for who she truly is, not just for her image. She recognizes that she has often presented a curated version of herself to the world, and she seeks to break free from this performance.

- She wants to be seen as more than just a sex symbol, as someone with thoughts, feelings, and ideas.

- She seeks to create a life that is aligned with her values and her true self.

- This desire for authenticity is a driving force in her journey of self-discovery.

The illusion of control. The author explores the illusion of control, recognizing that she has often tried to control her image and her narrative, but that this has ultimately been futile. She realizes that she cannot control how others perceive her, and that she must learn to accept herself as she is.

- She recognizes that her attempts to control her image have often led to feelings of anxiety and insecurity.

- She seeks to let go of the need for control and to embrace vulnerability.

- This process of letting go is a crucial step in her journey of self-acceptance.

Embracing vulnerability. The author learns to embrace vulnerability as a source of strength, recognizing that it is through vulnerability that she can connect with others and find true intimacy. She seeks to create a life that is authentic and meaningful, not just one that is pleasing to others.

- She recognizes that vulnerability is not a weakness, but rather a sign of courage and authenticity.

- She seeks to create relationships that are based on honesty and openness.

- This process of embracing vulnerability is a crucial step in her journey of self-discovery and self-acceptance.

Last updated:

FAQ

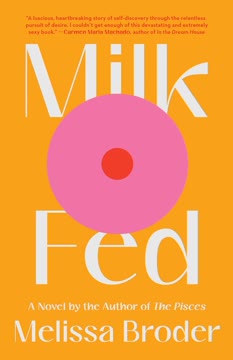

What's "My Body" by Emily Ratajkowski about?

- Exploration of Identity: "My Body" is a collection of essays where Emily Ratajkowski explores her identity, experiences, and the complexities of being a woman in the public eye.

- Themes of Empowerment: The book delves into themes of empowerment, objectification, and the societal expectations placed on women's bodies.

- Personal Narratives: Ratajkowski shares personal stories from her life, including her experiences in the modeling industry and her reflections on fame and self-image.

- Cultural Commentary: The book also serves as a cultural commentary on the intersection of feminism, capitalism, and the commodification of women's bodies.

Why should I read "My Body" by Emily Ratajkowski?

- Insightful Perspective: The book offers a unique perspective from someone who has been both celebrated and criticized for her appearance and public persona.

- Candid Reflections: Ratajkowski provides candid reflections on her personal experiences, making it a relatable read for those interested in the complexities of modern womanhood.

- Cultural Relevance: It addresses timely issues such as body image, feminism, and the impact of social media, making it relevant to contemporary discussions.

- Empowerment and Self-Discovery: Readers may find inspiration in Ratajkowski's journey of self-discovery and empowerment, as she navigates the challenges of being a woman in a male-dominated industry.

What are the key takeaways of "My Body" by Emily Ratajkowski?

- Body Autonomy: The book emphasizes the importance of body autonomy and the right to control one's own image and narrative.

- Complexity of Empowerment: Ratajkowski explores the complexity of empowerment, questioning whether true empowerment can be achieved within a patriarchal system.

- Impact of Objectification: She discusses the impact of objectification on self-esteem and identity, highlighting the challenges of being seen primarily as a physical entity.

- Navigating Fame: The book provides insights into the challenges and contradictions of navigating fame and public scrutiny as a woman.

How does Emily Ratajkowski address feminism in "My Body"?

- Feminism and Choice: Ratajkowski discusses feminism in the context of choice, arguing that true feminism allows women to make their own decisions about their bodies and careers.

- Critique of Feminist Movements: She critiques certain feminist movements for not fully embracing the complexities of women's choices, especially in the context of sexuality and empowerment.

- Personal Feminist Journey: The book reflects her personal journey with feminism, including her evolving understanding of what it means to be a feminist in today's world.

- Intersection with Capitalism: Ratajkowski examines how capitalism intersects with feminism, particularly in the commodification of women's bodies.

What are the best quotes from "My Body" and what do they mean?

- "The power of my body": This quote reflects Ratajkowski's exploration of how her body has been both a source of empowerment and objectification.

- "Feminism is about choice": It underscores her belief that feminism should prioritize women's autonomy and the freedom to make their own choices.

- "Navigating a patriarchal world": This quote highlights the challenges women face in a society that often values them for their appearance rather than their abilities.

- "Owning my narrative": Ratajkowski emphasizes the importance of controlling her own story and resisting societal pressures to conform to certain roles.

How does Emily Ratajkowski explore the concept of empowerment in "My Body"?

- Empowerment vs. Objectification: Ratajkowski examines the fine line between empowerment and objectification, questioning whether true empowerment is possible within a patriarchal framework.

- Personal Empowerment Journey: She shares her personal journey of empowerment, including the struggles and triumphs she has faced in reclaiming her narrative.

- Empowerment through Choice: The book argues that empowerment comes from having the freedom to make one's own choices, even if those choices are controversial or misunderstood.

- Critique of Empowerment Narratives: Ratajkowski critiques mainstream empowerment narratives that often fail to account for the complexities and contradictions of real-life experiences.

What role does social media play in "My Body" by Emily Ratajkowski?

- Platform for Expression: Social media is portrayed as a platform for self-expression and control over one's image, allowing Ratajkowski to share her narrative on her terms.

- Double-Edged Sword: The book discusses the double-edged nature of social media, where it can both empower and objectify, depending on how it is used.

- Public Scrutiny: Ratajkowski addresses the intense public scrutiny that comes with social media presence, highlighting the pressure to maintain a certain image.

- Influence on Identity: Social media's influence on identity and self-perception is a recurring theme, as Ratajkowski navigates the challenges of being both a public figure and a private individual.

How does Emily Ratajkowski discuss body image in "My Body"?

- Personal Experiences: Ratajkowski shares personal experiences with body image, including the pressures and expectations she has faced in the modeling industry.

- Cultural Critique: The book critiques cultural standards of beauty and the impact they have on women's self-esteem and identity.

- Body Positivity: Ratajkowski advocates for body positivity and acceptance, emphasizing the importance of embracing one's unique physicality.

- Complex Relationship: She explores her complex relationship with her body, acknowledging both the empowerment and challenges it has brought her.

What insights does "My Body" provide about the modeling industry?

- Behind-the-Scenes Look: The book offers a behind-the-scenes look at the modeling industry, revealing the pressures and expectations placed on models.

- Objectification and Control: Ratajkowski discusses the objectification and lack of control models often experience, highlighting the industry's impact on self-image.

- Empowerment through Modeling: Despite the challenges, she also explores how modeling has been a source of empowerment and financial independence for her.

- Industry Critique: The book critiques the industry's narrow standards of beauty and the commodification of women's bodies.

How does Emily Ratajkowski address the theme of identity in "My Body"?

- Identity and Public Persona: Ratajkowski explores the tension between her public persona and her private identity, questioning how fame has shaped her sense of self.

- Evolving Identity: The book reflects her evolving identity, as she navigates the complexities of being a woman in the public eye.

- Intersection of Identity and Body: Ratajkowski examines how her identity is intertwined with her body, and the challenges of being seen primarily as a physical entity.

- Search for Authenticity: Throughout the book, she seeks authenticity and self-acceptance, striving to define her identity on her own terms.

What challenges does Emily Ratajkowski face in "My Body"?

- Public Scrutiny: Ratajkowski faces the challenge of intense public scrutiny and the pressure to maintain a certain image.

- Balancing Empowerment and Objectification: She grapples with balancing empowerment and objectification, questioning whether true empowerment is possible within a patriarchal system.

- Navigating Fame: The book highlights the challenges of navigating fame and the contradictions of being a public figure.

- Personal and Professional Struggles: Ratajkowski shares personal and professional struggles, including the impact of societal expectations on her self-esteem and identity.

Review Summary

My Body receives mixed reviews, with praise for Ratajkowski's writing and raw honesty about her experiences in the modeling industry. Many readers appreciate her vulnerability and thought-provoking exploration of feminism, body image, and power dynamics. However, some criticize the book for lacking depth in its analysis of broader societal issues. Reviewers note the author's self-awareness and ability to grapple with contradictions in her life. Overall, the book is seen as a personal memoir that sparks discussions about women's bodies and agency in a capitalist society.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.