Key Takeaways

1. The Philosophical Quest Begins: Wonder and Fundamental Questions

. . . the only thing we require to be good philosophers is the faculty of wonder . . .

Philosophy starts with a sense of wonder about the world and our place in it. Unlike casual interests, philosophical questions are fundamental and universal, concerning everyone regardless of their background. They address the deepest mysteries of existence, such as where the world came from and who we are.

Basic human needs like food and shelter are essential, but philosophers argue that humans also need to understand their existence. This innate curiosity drives the search for meaning beyond mere survival. The world is often experienced with the same incredulity as a magic trick, prompting us to ask how it all works.

Children and philosophers share this vital faculty of wonder. As people grow older, they often become accustomed to the world, losing their astonishment. Philosophers strive to regain this childlike perspective, viewing the world as bewildering and enigmatic, and tirelessly pursuing answers to life's most profound questions.

2. From Myth to Reason: The First Philosophers

. . . nothing can come from nothing . . .

Early human cultures explained the world through myths, stories about gods and supernatural forces. These myths provided answers to questions about nature, life, and the struggle between good and evil, often involving rituals and offerings to influence divine powers.

The Greek philosophers marked a decisive break from this mythological worldview around 600 B.C. They sought natural, rather than supernatural, explanations for natural processes. This shift from mythos to logos (reason) laid the foundation for scientific thinking.

Pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes focused on finding a single basic substance underlying all things (water, the boundless, air). Later, Parmenides argued against change, while Heraclitus emphasized constant flux. Empedocles proposed four elements (earth, air, fire, water) combined by love and strife, and Democritus introduced the concept of eternal, indivisible atoms as the building blocks of reality.

3. Socrates: The Wisest Who Knows Nothing

. . . wisest is she who knows she does not know . . .

Socrates, the enigmatic Athenian philosopher (470-399 B.C.), never wrote anything down, yet profoundly influenced Western thought. Known through Plato's dialogues, he spent his life in public spaces, engaging citizens in philosophical discussions, believing that true understanding comes from within.

Using Socratic irony, he feigned ignorance to expose weaknesses in others' arguments, helping them "give birth" to correct insights. He believed that innate reason allows everyone, regardless of status, to grasp philosophical truths. His method challenged conventional wisdom and authority.

Accused of impiety and corrupting youth, Socrates was sentenced to death. He chose to die for his convictions, valuing truth and conscience above life. Like Jesus, he was a charismatic figure who challenged societal norms and whose death cemented his legacy, inspiring generations of thinkers.

4. Plato: The Realm of Eternal Forms

. . . a longing to return to the realm of the soul . . .

Plato (428-347 B.C.), Socrates' pupil, sought eternal and immutable truths in a world of constant change. Disturbed by Socrates' unjust death, he envisioned an ideal society governed by philosophers, believing that true reality lies beyond the sensory world.

His theory of Ideas posits a world of eternal, perfect forms (like "idea horse" or "idea justice") that are more real than the imperfect, changing things we perceive with our senses. These Ideas are timeless patterns that material things are modeled after, accessible only through reason.

The Myth of the Cave illustrates this: prisoners seeing only shadows (sensory world) mistake them for reality, while a freed prisoner (philosopher) discovers the true world outside (world of Ideas). Plato believed the soul, immortal and existing before the body, yearns to return to this world of Ideas, experiencing the sensory world as an imperfect reflection.

5. Aristotle: Observing the World as It Is

. . . a meticulous organizer who wanted to clarify our concepts . . .

Aristotle (384-322 B.C.), Plato's student, was Europe's first great biologist and a meticulous organizer of knowledge. Unlike Plato, he believed true reality lies in the sensory world, studying nature through observation and the senses, not just reason.

He rejected Plato's world of Ideas, arguing that "forms" are inherent in things themselves, not separate entities. A thing's "form" is its specific characteristics (e.g., a chicken's form is its ability to cackle and lay eggs), inseparable from its "substance" (what it's made of).

Aristotle classified nature into categories (living/nonliving, plant/animal/human) based on their characteristics and potential. He also proposed four causes (material, efficient, formal, final) for everything, including a "final cause" or purpose in nature, and founded logic as a science to clarify concepts and valid arguments.

6. Hellenism: Seeking Happiness and Salvation

. . . a spark from the fire . . .

Following Aristotle's death, the Hellenistic period (c. 323-31 B.C.) saw Greek culture spread widely under Alexander the Great. This era was marked by cultural fusion (syncretism) and a shift in philosophy towards finding personal happiness and salvation in a changing world.

Philosophical schools like Cynicism (happiness in self-sufficiency), Stoicism (accepting destiny, universal reason), and Epicureanism (pleasure as highest good, avoiding pain) emerged, focusing on ethics and individual well-being rather than grand metaphysical systems.

Neoplatonism, inspired by Plato, sought union with the divine "One," viewing the soul as a "spark from the fire" yearning to return to its source. This mystical trend, emphasizing inner experience and purification, blurred the lines between philosophy and religion, influencing later Christian thought.

7. Faith and Reason: Philosophy in the Christian Middle Ages

. . . going only part of the way is not the same as going the wrong way . . .

The Middle Ages (c. 400-1400) were dominated by Christian thought, inheriting elements from both Greek philosophy and Semitic religion. A central question was the relationship between Christian revelation (faith) and Greek philosophy (reason).

St. Augustine (354-430), influenced by Neoplatonism, "christianized" Plato, placing the Ideas in God's mind before creation. He saw history as a struggle between the "City of God" and the "City of the World," emphasizing faith's primacy but using reason to understand divine truths.

St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) "christianized" Aristotle, creating a synthesis of faith and knowledge. He argued that reason and faith could lead to the same truths (like God's existence), with faith providing access to truths beyond reason. He believed reason could go "part of the way" without being wrong.

8. The Renaissance and the Dawn of Modernity

. . . O divine lineage in mortal guise . . .

The Renaissance (c. 14th-16th centuries) marked a "rebirth" of classical antiquity, shifting focus from God back to man (humanism). This era celebrated human potential, individualism, and genius, contrasting with the medieval emphasis on human sinfulness.

New inventions like the compass, firearms, and printing press facilitated exploration, warfare, and the spread of ideas, challenging old authorities like the Church. A monetary economy and rising middle class fostered independence from feudal structures.

A new view of nature emerged, seeing it as positive and even divine (pantheism). The scientific method, emphasizing observation and experiment (empiricism), began to replace reliance on ancient texts, leading to revolutionary discoveries like Copernicus's heliocentric model, which fundamentally altered humanity's place in the cosmos.

9. The Age of Reason: Rationalism vs. Empiricism

. . . he wanted to clear all the rubble off the site . . .

The 17th and 18th centuries saw a vigorous debate between rationalism (knowledge from reason) and empiricism (knowledge from senses). Rationalists like Descartes sought certain knowledge through methodical doubt, famously concluding "Cogito, ergo sum" (I think, therefore I am), establishing the reality of thought and, through God's guarantee, external reality.

Descartes proposed a dualism of thought (mind) and extension (matter), distinct substances originating from God. He saw the body as a machine but the mind as independent, though interacting via the pineal gland. This mind-body problem became central.

Empiricists like Locke, Berkeley, and Hume argued all knowledge comes from sensory experience. Locke saw the mind as a "tabula rasa," receiving simple sensations to form complex ideas, distinguishing primary (objective) from secondary (subjective) qualities. Hume, the most consistent empiricist, questioned causality and the enduring self, arguing our beliefs are based on habit, not reason or experience. Berkeley, an idealist empiricist, denied material substance, claiming "to be is to be perceived," with things existing only in the mind of God.

10. Kant: Synthesizing Knowledge and Morality

. . . the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me . . .

Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) sought to reconcile rationalism and empiricism. He agreed with empiricists that knowledge begins with senses but argued that the mind actively shapes experience. Our reason provides "forms of intuition" like time and space, and concepts like causality, which structure how we perceive the world.

He distinguished between "the thing in itself" (unknowable reality) and "the thing for me" (reality as perceived through our mental framework). While we can't know ultimate truths (God, soul, universe's limits) through reason or senses, these questions are inherent to human thought.

Kant established a basis for morality in "practical reason," proposing the "categorical imperative": act only on maxims you'd universalize, and treat humanity always as an end, never merely a means. This innate moral law, like causality, is universal and absolute, providing a foundation for free will and faith in God and the immortal soul.

11. Romanticism and the World Spirit's Journey

. . . the path of mystery leads inwards . . .

Romanticism (c. 1800-1850) reacted against Enlightenment rationalism, emphasizing feeling, imagination, and yearning. Influenced by Kant's limits of knowledge and the ego's role, Romantics celebrated artistic genius and sought the "inexpressible" through art, comparing artists to God.

They yearned for distant times (Middle Ages) and places (Orient), exploring the "dark side" of life, mystery, and the supernatural. Nature was seen not as a mechanism but a living organism, an expression of a divine "world soul" or "world spirit," echoing earlier pantheistic and Neoplatonic ideas.

Philosophers like Schelling saw nature and mind as expressions of one Absolute. Herder emphasized history as a dynamic process, with each epoch and nation having its unique "soul." National Romanticism focused on folk culture, language, and myths, seeing the "people" as an organism, while Universal Romanticism sought the world spirit in nature and art.

12. Modern Challenges: History, Evolution, and Existence

. . . man is condemned to be free . . .

The 19th and 20th centuries brought new challenges to philosophy. Hegel saw history as the dialectical progress of "world spirit" towards self-consciousness, arguing that "the reasonable is that which is viable," with truth evolving historically.

Marx (historical materialism) countered Hegel, claiming material conditions drive history through class struggle, leading inevitably to communism. Darwin (biological evolution) showed life evolved through natural selection, challenging traditional creation views and placing humanity within nature. Freud (psychoanalysis) explored the unconscious, revealing irrational drives shaping human behavior.

Existentialism (Kierkegaard, Sartre) focused on individual existence, freedom, and responsibility in a world without inherent meaning. Sartre argued "existence precedes essence," meaning humans create their own nature and values, experiencing angst and alienation but condemned to be free and live authentically.

Last updated:

FAQ

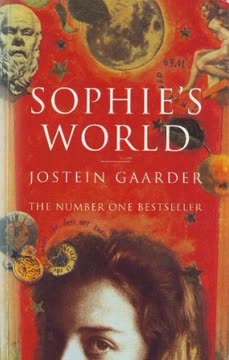

What is Sophie's World: A Graphic Novel About the History of Philosophy Vol I by Jostein Gaarder about?

- Philosophical journey through history: The book follows Sophie Amundsen, a young girl who embarks on a journey through the history of philosophy, guided by her mysterious mentor, Alberto Knox.

- Blending story and philosophy: It combines a coming-of-age narrative with accessible lessons on major philosophical ideas, thinkers, and epochs, from Socrates to Galileo and beyond.

- Meta-narrative intrigue: The story is layered with a mysterious subplot involving Hilde and her father, blurring the lines between fiction and reality.

- Imaginative teaching tools: Allegories like the white rabbit and the top hat are used to symbolize wonder and the unfolding of philosophical understanding.

Why should I read Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder?

- Accessible introduction to philosophy: The graphic novel format and engaging storytelling make complex philosophical concepts understandable for readers of all ages, especially beginners.

- Comprehensive historical overview: The book covers Western philosophy from ancient Greece through the Enlightenment and into modern thought, providing foundational knowledge.

- Encourages critical thinking: Through Sophie’s questions and Alberto’s guidance, readers are prompted to question assumptions, analyze ideas, and reflect on their own beliefs.

- Engaging and memorable narrative: The intertwining of mystery, personal growth, and philosophical lessons makes the content both entertaining and thought-provoking.

What are the key takeaways from Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder?

- Philosophy as self-discovery: The book emphasizes that philosophy is not just about learning facts, but about questioning existence, knowledge, and reality to better understand oneself.

- Historical and cultural context: Philosophical ideas are presented within their historical periods, showing how they evolved in response to cultural, religious, and scientific changes.

- Importance of wonder: Maintaining a sense of wonder and curiosity is portrayed as essential for philosophical inquiry and personal growth.

- Interconnectedness of ideas: The narrative demonstrates how philosophical concepts build upon and challenge each other, shaping the development of Western thought.

What is the "faculty of wonder" in Sophie's World and why does Jostein Gaarder emphasize it?

- Definition and importance: The "faculty of wonder" is the childlike ability to be astonished by the world and to question what is usually taken for granted.

- Philosophical foundation: Gaarder presents this as the starting point for all philosophical exploration, urging readers to never lose their curiosity.

- Contrast with indifference: The book warns against becoming "dim" or indifferent, suggesting that true philosophers keep their sense of wonder alive throughout life.

- Practical advice: Sophie is encouraged to choose a life of questioning and wonder, which is portrayed as the path to deeper understanding and fulfillment.

How does Jostein Gaarder explain the transition from mythological to philosophical thinking in Sophie's World?

- Mythological worldview origins: Early humans explained natural phenomena through myths involving gods and supernatural forces, using stories to make sense of the world.

- Philosophical critique emerges: Greek philosophers began to seek natural, rational explanations for the world, moving away from myth and superstition.

- Key figures and ideas: Thinkers like Xenophanes, Thales, and Anaximander questioned traditional myths and searched for fundamental substances or principles underlying reality.

- Significance of the shift: This transition marks the birth of philosophy and scientific reasoning, setting the stage for future intellectual developments.

What are the main ideas of the natural philosophers in Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder?

- Basic substance theories: Early philosophers like Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes proposed that everything originates from a fundamental substance such as water, the boundless (apeiron), or air.

- Debate on change and permanence: Parmenides argued that change is an illusion, while Heraclitus believed in constant change and the unity of opposites.

- Empedocles and Democritus: Empedocles introduced four elements and forces of love and strife, while Democritus developed the atom theory, suggesting everything is made of indivisible atoms.

- Foundation for science: These ideas laid the groundwork for scientific inquiry and the search for natural laws.

How does Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder portray Socrates and his philosophical method?

- Socratic questioning: Socrates is depicted as a gadfly who uses probing questions and irony to expose ignorance and stimulate critical thinking.

- Focus on ethics: He emphasized self-knowledge, virtue, and the idea that understanding what is right leads to right action.

- Legacy through Plato: Socrates wrote nothing himself, but his ideas and methods were preserved and expanded by his student, Plato.

- Martyr for philosophy: His trial and execution for "corrupting the youth" highlight his commitment to truth and the philosophical life.

What is Plato’s theory of ideas as explained in Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder?

- World of forms: Plato distinguishes between the changing sensory world and the eternal, perfect world of ideas or forms, which are the true reality.

- Examples and metaphors: The book uses analogies like identical cookies from a mold and the Myth of the Cave to illustrate how forms are the patterns behind all things.

- Knowledge and the soul: True knowledge is knowledge of the forms, and the soul is believed to remember these forms from before birth.

- Philosophical implications: Plato’s theory supports the immortality of the soul and the idea of philosopher-kings ruling an ideal society.

How does Aristotle’s philosophy differ from Plato’s in Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder?

- Rejection of separate forms: Aristotle argues that forms do not exist independently but are the characteristics of things themselves, inseparable from their substance.

- Empirical approach: He emphasizes observation, categorization, and logic, laying the foundation for biology and scientific method.

- Substance and change: Aristotle introduces the concepts of substance, form, potentiality, and actuality to explain how things change and develop.

- Ethics and the Golden Mean: His ethical philosophy centers on achieving balance and moderation for a good life.

How does Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder explain the Middle Ages and its philosophy?

- Cultural bridge: The Middle Ages are presented as a period of growth and synthesis between antiquity and the Renaissance, not just a "Dark Age."

- Christianization of philosophy: Thinkers like St. Augustine and Aquinas blended Greek philosophy with Christian theology, debating the relationship between faith and reason.

- Role of the church: Monasteries and the church were centers of learning, preserving and transmitting philosophical ideas.

- Women and wisdom: The book highlights figures like Hildegard of Bingen and the concept of Sophia, the female aspect of divine wisdom.

What is the significance of the Renaissance and Enlightenment in Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder?

- Rebirth of humanism: The Renaissance revived classical Greek and Roman ideas, emphasizing individual worth, creativity, and the rediscovery of ancient texts.

- Scientific revolution: Figures like Galileo and Newton introduced empirical methods and mathematical laws, transforming humanity’s understanding of nature.

- Challenging old worldviews: The heliocentric model and new technologies shifted perspectives on humanity’s place in the universe.

- Enlightenment ideals: The Enlightenment promoted reason, skepticism of authority, and the pursuit of knowledge, laying the groundwork for modern philosophy.

How does Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder present modern philosophy, including Kant, Hegel, Marx, Darwin, Freud, and existentialism?

- Kant’s synthesis: Kant reconciles empiricism and rationalism, arguing that knowledge arises from sensory experience shaped by innate mental structures, and introduces the categorical imperative in ethics.

- Hegel’s dialectic: Hegel’s philosophy emphasizes the evolution of truth and reason through history via thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, focusing on the "world spirit."

- Marx’s materialism: Marx shifts focus to material conditions and class struggle as drivers of historical change, critiquing capitalism and advocating for a classless society.

- Darwin and Freud: Darwin’s theory of evolution and Freud’s psychoanalysis challenge traditional views of human nature, emphasizing natural selection and the unconscious mind.

- Existentialism: Twentieth-century existentialists like Sartre and Kierkegaard focus on individual freedom, responsibility, and the creation of personal meaning in a world without inherent purpose.

What are the best quotes from Sophie's World by Jostein Gaarder and what do they mean?

- “Cogito, ergo sum.” (Descartes): Asserts the certainty of self-awareness as the foundation of all knowledge.

- “Our heart is not quiet until it rests in Thee.” (St. Augustine): Expresses the soul’s longing for divine peace, central to medieval philosophy.

- “All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players.” (Shakespeare): Reflects on the performative and transient nature of human life, echoing Baroque themes.

- “Two things fill my mind with ever-increasing wonder and awe... the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me.” (Kant): Highlights the dual sources of wonder—nature and morality—that inspire philosophical reflection.

- “Happy birthday, Hilde! As I’m sure you’ll understand, I want to give you a present that will help you grow.” (Hilde’s father): Symbolizes the gift of philosophical knowledge and the journey of personal growth

Review Summary

Sophie's World graphic novel adaptation receives mostly positive reviews, praised for its accessible presentation of philosophy and engaging visuals. Readers appreciate the updated content and feminist perspective. Some note simplification of complex ideas but find it suitable for newcomers to philosophy. The book's humor, creativity, and ability to make philosophical concepts understandable are highlighted. A few reviewers mention eagerness for the second volume. Overall, it's seen as a successful adaptation that maintains the spirit of the original while appealing to modern audiences.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.