Key Takeaways

1. Accurate Transcripts are Crucial for Intellectual History

Previous interpretations and nearly four decades of scholarly quotation have placed virtually complete trust on a transcript of somewhat uncertain origin, which was-to be generous-inexact.

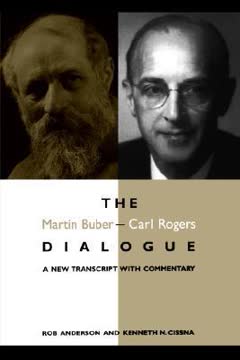

Flawed historical record. The 1957 dialogue between philosopher Martin Buber and psychologist Carl Rogers is a seminal event in the history of humanistic thought, frequently cited to compare their ideas on interpersonal relationships. Despite its significance, all previously published transcripts of this conversation contain numerous inaccuracies, stemming from an original flawed typescript and subsequent edits that prioritized readability over fidelity. These errors, ranging from minor word changes to significant mishearings, have distorted the historical record and led to misinterpretations of the dialogue's substance and process.

Re-examining the source. This new annotated transcript corrects hundreds of these errors by relying on a fresh, systematic listening to the original audiotape. The goal is not merely to fix typos, but to restore the authentic words, vocal inflections, pauses, and interjections that reveal the true dynamics of the conversation. Understanding what Buber and Rogers actually said, and how they said it, is essential for a deeper appreciation of their intellectual exchange and its implications.

Unveiling hidden layers. The corrected transcript provides a more reliable foundation for scholars to analyze the interplay between Buber's philosophical anthropology and Rogers's client-centered psychotherapy. It highlights how their differing interpersonal styles, the presence of an audience, and their assigned roles as questioner and respondent shaped the dialogue. This meticulous re-evaluation ensures that future discussions of this pivotal meeting are grounded in an accurate representation of the event.

2. Mutuality in Therapy: Moments vs. Inherent Inequality

But I [Buber: Huh] suspect that in those moments [Buber: Uh huh] when, um, when real change occurred [Buber: Uh huh], that it would be because there had been a real meeting of persons in which um it was experienced the same from both sides.

Rogers's "moments" of equality. Carl Rogers emphasized that while the overall therapeutic relationship might appear unequal due to differing roles, there are "effective moments" where a genuine meeting of persons occurs, experienced as equal by both therapist and client. In these crucial instances, the client senses the therapist's understanding and acceptance, leading to mutual change and growth. Rogers clarified that he was not advocating for constant, full mutuality, but for these intense, transformative junctures.

Buber's insistence on limits. Martin Buber, however, maintained that the therapeutic situation inherently imposes limits on full mutuality. He argued that the client comes for help, is entangled in the therapist's life, and cannot see or know the therapist in the same way the therapist sees the client. Buber asserted that the therapist is "at your side and at his side at the same time," capable of experiencing the situation from both perspectives, a capacity the client lacks.

Clarifying the disagreement. The corrected transcript reveals that Buber eventually conceded that a kind of equality is possible, but only for "minutes" or "one moment," and that these moments are "made possible by you [the therapist]." This nuanced agreement, often overlooked in previous transcripts, shows that their positions were closer than commonly assumed, with both recognizing the therapist's unique role in facilitating these brief, yet profound, experiences of shared humanity.

3. Inner Meeting: Dialogue with Self or Problem of Language?

You call something eh dialogue [Rogers overlaps: Um hum] that I cannot call so.

Rogers's inner meeting. Carl Rogers introduced the concept of a person's "relationship to himself," describing vivid moments in therapy where individuals meet previously unrecognized aspects of themselves—feelings, meanings, or courage. He suggested that this inner encounter shares the same quality as a "real meeting relationship" with another, and is crucial for a person's capacity to then meet others in an I-Thou relationship.

Buber's objection to "dialogue." Martin Buber, however, objected to calling this inner experience "dialogue," citing a "problem of language." He argued that true dialogue requires "otherness" and the "moment of surprise," which he believed were absent in an internal process. Buber used the metaphor of a chess game, where the charm lies in the unpredictable actions of an external partner, distinguishing it from surprising oneself.

Semantic confusion and missed nuance. The new transcript highlights that Rogers consistently used the term "meeting" for this inner experience, not "dialogue," suggesting Buber may have misheard or presumed a broader meaning. While Buber never fully elaborated on what he would call this phenomenon, his later writings referred to it as an "intrapsychic dialectic" or "thinking," acknowledging its importance while maintaining his strict definition of interpersonal dialogue. This semantic distinction, though seemingly minor, underscored a fundamental difference in their conceptual frameworks.

4. Human Nature: Constructive Tendency vs. Polar Reality

I see his whole polarity and then I see how the worst in him and the best in him are dependent on one another, attached to one another.

Rogers's trust in the positive. Carl Rogers articulated his belief in the "actualizing tendency," suggesting that basic human nature is inherently constructive and trustworthy. He argued that if individuals are freed from constraints and ignorance, they will tend towards growth, socialization, and better interpersonal relationships, without needing external motivation towards the positive. This contrasted sharply with psychoanalytic views of human nature as needing control.

Buber's polar reality. Martin Buber offered a different perspective, describing human nature as a "polar reality." He saw individuals as embodying a dynamic interplay of opposing forces, not simply good or evil, but rather "yes and no," or "acceptance and refusal." Buber believed that true help involves recognizing this inherent polarity and assisting the individual in strengthening the positive pole and bringing "direction" and "order" to a potentially chaotic state.

A difference of emphasis. While Buber framed his "polar reality" as "near to what" Rogers said "but somewhat different," some commentators have exaggerated this as a stark contrast. The corrected transcript, including Rogers's "Right" in response to Buber's elaboration, suggests a greater degree of implicit agreement. Both thinkers ultimately aimed to facilitate human flourishing, with Rogers emphasizing the release of inherent potential and Buber focusing on the dynamic interplay and direction of that potential.

5. Acceptance vs. Confirmation: A Nuanced Distinction

Accepting, this is just eh accepting how the other is in this moment, in this eh actuality of his. Confirming means [4.5] first of all, eh, accepting the whole potentiality of the the other.

Friedman's clarifying question. Moderator Maurice Friedman introduced the terms "acceptance" (Rogers) and "confirmation" (Buber) to explore potential similarities or differences. He quoted Rogers's definition of acceptance as a "warm regard for the other and a respect for his individuality," including "an acceptance of and regard for his attitudes of the moment, no matter how negative or positive." Friedman then asked if Buber's "confirmation" was similar or included a "demand on the other."

Buber's two-tiered concept. Buber distinguished between the two: "acceptance" means acknowledging the other "just as he is" in their present actuality. "Confirmation," however, goes deeper, involving the acceptance of the other's "whole potentiality" and actively helping to realize "the person he has been created to become." Buber clarified that this is not about demanding change, but about discovering and fostering the other's inherent possibilities through an "accepting love."

Semantic overlap and missed clarity. The new transcript reveals a crucial mishearing in previous versions, where Buber was quoted as saying confirmation is not expressed in "massive" terms, when he actually said "missive" terms, meaning it's implicitly communicated, not explicitly demanded. Rogers later affirmed that his "acceptance" also encompassed the individual's potentiality, suggesting that their concepts were more aligned than their differing terminology implied. The dialogue, unfortunately, did not fully resolve this semantic overlap, leaving a perceived distinction that was perhaps less fundamental than it appeared.

6. Dialogue Dynamics: Roles, Audience, and Interruption

And the form of this dialogue will be that Dr. Rogers will himself raise questions with Dr. Buber and Dr. Buber will respond, and perhaps with a question, perhaps with a statement.

Structured interaction. The dialogue was not a free-flowing conversation but a structured event with assigned roles: Rogers as the primary questioner, Buber as the respondent, and Friedman as the moderator. This format, explicitly stated by Friedman, influenced the conversational dynamics, with Rogers often deferring to Buber and Buber sometimes adopting a more didactic tone. The new transcript highlights how these roles shaped the flow of ideas and the participants' rhetorical choices.

Audience as co-author. The presence of a large public audience also played a significant role, transforming the event into what Friedman called a "trialogue" or "quatralogue." The audience's laughter, applause, and even shouted suggestions (like "quotes" to help Buber find a word) demonstrate their active, albeit mostly silent, participation. Buber, who initially doubted the possibility of genuine dialogue in public, implicitly acknowledged the audience's influence by noting that dialogue could be "silent."

Interruption and conversational control. The corrected transcript reveals numerous instances of interruptions and vocal encouragers, which were largely omitted in previous versions. These details offer insights into the participants' engagement, their attempts to clarify or redirect the conversation, and moments of conversational control. For example, Buber's occasional redirection of Rogers or his calling on Friedman to speak, despite Rogers being mid-sentence, illustrates the complex negotiation of turns and topics in this unique public intellectual exchange.

7. Buber's Call for Precision in Psychological Terminology

I'm I have learned in the course of my life to appreciate terms. [Rogers: Uh hum] Eh, when, ehand I think that modern psychology, eh does it not in sufficient measure.

Critique of "modern psychology." Martin Buber expressed a strong belief in the importance of precise terminology, stating that "when I find something that is essentially different from another thing, I want a new term." He then critiqued "modern psychology" for its insufficient appreciation of terms, implicitly directing this criticism towards Rogers, the only psychologist on stage. Buber used the example of the "unconscious," arguing that it was conceptually problematic to label it simply as a "mode of the psychic" given its profound differences from conscious experience.

Rogers's provisionality. Rogers, in contrast, often used terms provisionally, acknowledging their limitations and inviting Buber to suggest better phrasing, as seen in his question about "human nature." While Buber's critique of imprecise language was a consistent theme in his work, its direct application in the dialogue, particularly after Rogers had just suggested semantic differences, underscored a tension in their intellectual styles. Buber's example of the unconscious, a psychoanalytic concept Rogers had long moved beyond, further highlighted a potential disconnect in their understanding of each other's specific psychological frameworks.

Impact on the dialogue. This emphasis on precise terminology contributed to some of the dialogue's perceived disagreements, particularly regarding the "inner meeting" and the distinction between "acceptance" and "confirmation." Buber's insistence on distinct terms for distinct phenomena, while philosophically rigorous, sometimes overshadowed the underlying conceptual similarities that Rogers attempted to articulate from his experiential perspective. The corrected transcript clarifies these exchanges, showing Buber's consistent intellectual demand for conceptual clarity.

8. The Dialogue's Enduring Impact on Both Thinkers

This recognition of the significance of what Buber terms the I-thou relationship is the reason why, in client-centered therapy, there has come to be a greater use of the self of the therapist, of the therapist's feelings, a greater stress on genuineness, but all of this without imposing the views, values, or interpretations of the therapist on the client.

Rogers's deepened practice. Although Rogers felt some of his ideas were misunderstood, the dialogue profoundly influenced his subsequent work. He cited Buber more frequently, and his client-centered therapy evolved to place even greater emphasis on the therapist's "self," "feelings," and "genuineness" in the therapeutic relationship. This shift, as Rogers himself noted, was a direct result of recognizing the significance of Buber's I-Thou concept, leading to a more philosophical and relationally focused approach to communication and social responsibility.

Buber's revised views. Martin Buber, too, was impacted, notably changing his previous strong conviction that genuine dialogue was impossible in public or when recorded. He described the meeting as a "memorable occasion" and, in his 1958 postscript to I and Thou, elaborated on psychotherapy in terms that strikingly echoed Rogers's approach. Buber emphasized the "person-to-person attitude of a partner" and the "regeneration of an atrophied personal centre," aligning with Rogers's focus on the client's inherent growth potential.

A pivotal intellectual exchange. Despite perceived disagreements and Buber's private comment about treating Rogers "gently like a boy," the dialogue served as a critical incident for both. It pushed Rogers to articulate the philosophical underpinnings of his practice more explicitly and prompted Buber to refine his application of dialogic principles to psychotherapy and public discourse. The corrected transcript illuminates this mutual influence, revealing a productive immediacy that enriched the intellectual legacies of two of the 20th century's most significant thinkers.

Last updated:

Review Summary

Readers highly praise The Martin Buber–Carl Rogers Dialogue, giving it an average rating of 4.13 out of 5. They appreciate the unique opportunity to witness a conversation between two intellectual giants and gain insights into different perspectives on dialogue. Reviewers found the book enlightening, noting its value in teaching better listening and personal growth. The analysis of the dialogue was particularly appreciated. Some readers expressed a desire to learn more about Rogers as a person. Minor criticism was directed at the verbatim transcription, which included every verbal pause.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.