Key Takeaways

1. The Unique Landscape of Cape Cod's Outermost House

My house stood by itself atop a dune, a little less than halfway south on Eastham bar.

Dynamic frontier. Cape Cod's outer beach, a "last defiant bulwark" against the open Atlantic, is a solitary and elemental landscape. This twenty-mile stretch, shaped by ancient plains and glacial drift, is in constant battle with the sea, its sands and clays perpetually replenished or eroded by wind and waves. It is a place where nature's great rhythms hold "spacious and primeval liberty."

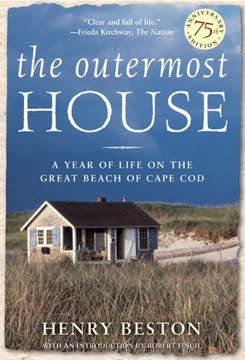

A year's dwelling. The author, Henry Beston, initially built a modest two-room cottage, the "Fo'castle," on Eastham bar as a vacation retreat. However, the profound "beauty and mystery of this earth and outer sea" so possessed him that he lingered, ultimately deciding to live there for a full year, seeking to know and share its "mysterious and elemental life."

Isolated sanctuary. His small house, compact and strong, featured ten windows offering panoramic views of the sea to the east and the marshes to the west. Despite its isolation, Beston found fresh water by driving a well pipe into the dune and relied on driftwood fires and oil lamps, embracing a life intimately connected to the raw, untamed environment.

2. The Elemental Power and Voices of the Ocean

The three great elemental sounds in nature are the sound of rain, the sound of wind in a primeval wood, and the sound of outer ocean on a beach.

Ocean's symphony. The sea's sound is far from monotonous; it is a complex, varied symphony. Listen closely, and one discerns "hollow boomings and heavy roarings, great watery tumblings and tramplings, long hissing seethes, sharp, rifle-shot reports, splashes, whispers, the grinding undertone of stones." This soundscape constantly shifts in tempo, pitch, and rhythm, reflecting every subtle change in wind and tide.

Triple rhythm. A peculiar and observed phenomenon on this coast is the approach of great waves in threes. "Three great waves, then an indeterminate run of lesser rhythms, then three great waves again." This "triple rhythm" is well-known to Coast Guard crews, who use the lull after the third wave to launch their boats, a testament to the sea's predictable yet formidable power.

Constant transformation. The ocean is a ceaseless force, forever embodying itself in a succession of watery shapes that vanish upon its passing. Beston describes it as "endless charging, endless incoming and gathering, endless fulfilment and dissolution, endless fecundity, and endless death," a continuous process that shapes the beach and profoundly influences the author's experience.

3. The Rhythmic Pageant of Migratory Birds

For the animal shall not be measured by man. In a world older and more complete than ours they move finished and complete, gifted with extensions of the senses we have lost or never attained, living by voices we shall never hear.

Autumnal migrations. Autumn brings an "enormous population" of migratory shorebirds to Eastham sands, gathering, resting, and feeding in disciplined flocks. These "constellations of birds" move with a collective will, their synchronous flights a mystery of nature, challenging human-centric views of animal intelligence and revealing a profound unity in their movements.

Land birds at sea. Surprisingly, many land birds, like warblers and sparrows, also traverse this coastal arm, undertaking "a gesture of ancient faith and present courage" over the open ocean. The Cape serves as a crucial stopover, witnessing a diverse array of species from the Arctic to the tropics, often arriving unexpectedly on the dunes after long flights.

Winter residents. As smaller birds depart south, hardy arctic sea ducks, auks, and murres arrive, finding the open, deserted Cape a "Florida" for their wintering. These "outermost waters" inhabitants rarely come ashore, living and feeding entirely at sea, though they face new threats like oil pollution, which mats their feathers and hinders their ability to survive.

4. Winter's Desolation and Hidden Life

A year indoors is a journey along a paper calendar; a year in outer nature is the accomplishment of a tremendous ritual.

Winter's embrace. Winter transforms the Cape into a stark, elemental landscape, marked by icy winds, pelting rain, and sweeping snow squalls. The sand loses its fluidity, becoming "cold silver-grey," and the vibrant summer vegetation thins, revealing the dune's bare body. Footprints, which summer would erase in minutes, can remain for days or weeks in the frozen sand.

Life's resilience. Despite the apparent desolation, life persists. Insect life retreats into "trillion, trillion tiny eggs" awaiting spring, while mammals like skunks and deer adapt or migrate to firmer ground. Beston observes seals reconnoitering for food and recounts the harrowing adventure of a young doe struggling through the ice-filled marsh, ultimately rescued by the Coast Guard.

Storm's fury. Midwinter brings fierce storms, like the February gale that caused shipwrecks and revealed ancient buried wreckage. These events underscore the raw power of nature, where human endeavors are dwarfed, and life and death are in constant, dramatic flux, leaving behind a landscape strewn with new and old debris.

5. Human Connection Amidst Solitude: Coast Guard and Shipwrecks

When the nights are full of wind and rain, loneliness and the thunder of the sea, these lights along the surf have a quality of romance and beauty that is Elizabethan, that is beyond all stain of present time.

Wardens of the Cape. Despite his chosen solitude, Beston is not truly alone, relying on the Coast Guard for connection and news. These "surfmen" patrol the fifty miles of beach day and night, their "solitary and mysterious" lantern lights a symbol of human courage and service against the elements, a constant presence in the vast darkness.

Shipwreck drama. The Cape's history is steeped in tales of shipwrecks, a constant reminder of the ocean's peril. Beston recounts the tragic stranding of the schooner Montclair, where five lives were lost, and the dramatic rescue efforts by the Coast Guard, highlighting their bravery and skill in treacherous conditions, often using breeches buoys to save crews.

Community and aid. Wrecks, though tragic, also reveal the Cape community's character. While some salvage materials, the primary concern is always for the shipwrecked, reflecting a deep-seated hospitality. The Coast Guard's "sound, traditional surf knowledge" allows them to navigate impossible conditions, embodying a profound respect for the sea and its dangers.

6. Spring's Renewal and Nature's Ardency

Nature’s eagerness to sow life everywhere, to fill the planet with it, to crowd with it the earth, the air, and the seas.

Awakening earth. Spring brings a cautious inflow of new energies, transforming the landscape with "new grass spears of a certain eager green" and the emergence of mammalian life. The ocean, though still cold, begins to reflect the increasing "splendour" of the April sun, gradually shedding its winter pallor.

Return of life. Migratory birds, like ringnecks and gannets, pause on their hurried journey north to breeding grounds, while marsh ducks and larks return to their inland habitats. The air fills with the sounds of courtship and renewed activity, a stark contrast to winter's silence, as birds "choose partners" and prepare for nesting.

Fish migrations. A profound natural event is the spring migration of fish, such as the alewives, who leave the sea to spawn in freshwater ponds. This "mysterious" journey, driven by an ancient instinct, showcases nature's relentless "ardency for the stir of life," as creatures endure immense struggle to fulfill their purpose, finding their way back to ancestral waters.

7. The Profound Beauty and Mystery of Night

Yet to live thus, to know only artificial night, is as absurd and evil as to know only artificial day.

Reverencing darkness. Beston argues that modern civilization has lost touch with the "holiness and beauty of night," fearing its vast serenity and the "austerity of stars." He believes that embracing natural night, free from artificial lights, is essential for a deeper human experience, fostering a "religious emotion" and "poetic mood."

Sensory immersion. On the great beach, night is a "true other half" of the day, filled with unique sensory details: the "endless wild uprush, slide, and withdrawal of the sea’s white rim of foam," the faint piping of the plover, and the "phosphorescence in the surf" turning the beach into a "dust of stars," where every footprint glows.

Cosmic connection. Night offers a glimpse of humanity "islanded in its stream of stars—pilgrims of mortality, voyaging between horizons across eternal seas of space and time." It is a moment where the human spirit is "ennobled by a genuine moment of emotional dignity," connecting us to the vastness and mystery of the universe, far beyond human concerns.

8. Engaging All Senses for Deeper Connection to Nature

We ought to keep all senses vibrant and alive. Had we done so, we should never have built a civilization which outrages them, which so outrages them, indeed, that a vicious circle has been established and the dull sense grown duller.

Beyond sight. Beston advocates for a fuller sensory engagement with nature, particularly emphasizing the often-neglected sense of smell. He finds "keen, vivid, and interesting savours and fragrances" on the beach, from the cool, moist air at the ocean's edge to the "hot, pungent exhalation of fine sand," a stark contrast to the "stench modern civilization breathes."

Olfactory landscape. The distinct aromas of the beach, such as the "good reek of hot salt grass" or the "iodine orange" of sun-ripened seaweed, are so familiar that he believes he could navigate the summer beach blindfolded by scent alone. This sensory richness allows for a deeper, more intimate understanding of the environment, beyond mere visual observation.

Holistic perception. For Beston, true comprehension of nature requires the full engagement of all senses, not just the dominant eye. This holistic approach allows for the creation of a "mood or of a moment of earth poetry," enriching the human experience and fostering a deeper reverence for the elemental world, keeping our senses "vibrant and alive."

9. The Natural Year as a Sacred Ritual

A year in outer nature is the accomplishment of a tremendous ritual.

Cosmic drama. Beston views the natural year not merely as a sequence of events but as a "tremendous ritual," a "burning ritual" driven by the "pilgrimages of the sun." This perspective elevates daily natural phenomena into a "great natural drama by which we live," fostering awe and joy in the cyclical unfolding of life.

Unchanging cycles. Despite human "violences" and "fantastic civilization," the earth's basic rhythms—the rising sun, flowing winds, and breaking waves—remain undisturbed. These recurring cycles provide a "safe and stable context," a fundamental integrity that sustains life and offers profound meaning, regardless of human affairs.

Humanity's dependence. Beston reminds us that our existence is deeply intertwined with these "deep, constant rhythms." The return of insects, the migration of birds, the tilt of the earth toward the sun—these are not just phenomena for enjoyment but "signs that the cosmos is still intact," essential for both biological survival and human meaning, grounding us in something larger and more reliable.

Last updated:

Review Summary

The Outermost House is a beloved nature writing classic, chronicling Henry Beston's year living on Cape Cod in the 1920s. Readers praise Beston's poetic prose and keen observations of the natural world, particularly his descriptions of birds, tides, and seasons. Many find the book meditative and transportive, offering a glimpse into a simpler time and deeper connection with nature. While some readers found parts slow or overly descriptive, most appreciate Beston's lyrical style and environmental insights. The book is considered influential in nature writing and Cape Cod conservation efforts.

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.