Key Takeaways

1. Failure is the Mother of Design Success

Desire, not necessity, is the mother of invention.

Dissatisfaction Drives Innovation. New things and ideas emerge from our discontent with the status quo. The failure of existing artifacts and technologies to meet our needs or expectations sparks the drive to improve them. This dissatisfaction, whether stemming from a broken part or a slow system, becomes the catalyst for innovation.

Isolating the Cause. The initial step towards a solution lies in pinpointing the root cause of the failure. By understanding why something isn't working, inventors, engineers, and designers can focus their efforts on avoiding, removing, or circumventing the problem. This targeted approach is essential for developing effective improvements.

Continuous Improvement. Even the best designs have limitations, and there is always room for improvement. The most successful advancements are those that directly address these limitations, focusing on the failures to create better solutions. This iterative process of identifying and overcoming failures is the engine of technological progress.

2. Design is a Paradoxical Dance of Success and Failure

Success and failure in design are intertwined.

Success Masks Potential Failures. While a focus on failure can lead to success, over-reliance on successful precedents can lead to future failures. Success is not simply the absence of failure; it can also mask potential modes of failure. Emulating success may be effective in the short term, but such behavior can surprisingly lead to failure itself.

Past Success is No Guarantee. A single type of rock that worked reasonably well as a hammer for every previously known task might be said to be the hammer-rock. However, there would arise a task in which the hammer-rock would fail. Past successes, no matter how numerous and universal, are no guarantee of future performance in a new context.

Anticipating Failure is Key. The book explores the interplay between success and failure in design and, in particular, describes the important role played by reaction to and anticipation of failure in achieving success. The vast majority of users of a technology adapt to its limitations. But it is in human nature to want to use things beyond their intended range.

3. Tangible and Intangible Designs Share the Same Principles

Most things have more than a single purpose, which obviously complicates how they must be designed and how they therefore can fail.

Design Extends Beyond Physical Objects. The principles of design and its limitations apply not only to concrete objects like projectors and pointers but also to intangible things. These include intellectual and symbolic constructs like national constitutions and flags, where the failure to anticipate how such politically charged things might not please their varied intended constituencies can be disastrous.

Games as Systems of Design. Strategies for playing games like basketball, while perhaps of lesser consequence than political contests, are also matters of design, and the failure of a coach to defend against a boring offense or to match a hot shooter with a tenacious defender can result in a disappointing game for players and spectators alike.

Anticipating Failure is Universal. Successful design, whether of solid or intangible things, rests on anticipating how failure can or might occur. Failure is thus a unifying principle in the design of things large and small, hard and soft, real and imagined.

4. Scale Matters: Small vs. Large Designs

Failure is thus a unifying principle in the design of things large and small, hard and soft, real and imagined.

Underlying Sameness of Design. Whatever is being designed, success is achieved by properly anticipating and obviating failure. Since earlier chapters focus primarily on smaller, well-defined things and contexts, this chapter also employs examples of larger things and systems, such as the steam engine and the railroad.

Behavioral Differences. With the underlying sameness of the design process established, the discussion turns to differences in the behavior of small and large things. In particular, the testing process, by which an unanticipated mode of failure is often first uncovered, must necessarily vary.

Testing and Consequences. Small things, which typically are mass produced in staggeringly large numbers, can be tested by sampling. However, very large things, which are essentially custom or uniquely built, do not present that same opportunity. And, because of their scale, the failure of large structures or machines can be devastating in all sorts of ways, not the least of which is economic.

5. Buildings: Ego, Hubris, and Structural Integrity

In the twenty-first century, limitations on the height of buildings are not so much structural as mechanical, economic, and psychological.

The Allure of Height. The desire to build tall did not originate with the skyscraper, it is in that genre of architecture and structural engineering that failure can have the most far-reaching consequences. The decision to build tall is often one of ego and hubris, qualities that not infrequently originate in and degenerate into human failings of character that can lead to structural ones.

Practical Limitations. Structural engineers know how to build buildings much taller that those now in existence, but they also understand that height comes only at a premium in space and money. The taller buildings go, the more people must be transported vertically in elevators. The more elevators that are needed, the more elevator shafts must be provided, thus taking up more and more volume.

Unforeseen Threats. Nevertheless, for reasons of pride and striving, taller buildings will continue to be built. Still, no matter how many supertall buildings stand around the world, their success does not guarantee that of their imitators. The collapse of the twin towers of the New York World Trade Center demonstrated that unanticipated outside agents (and unperceived internal weaknesses) can create scenarios that can trigger novel failure modes.

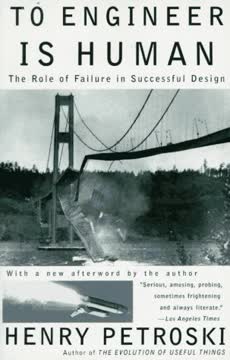

6. Bridges: Paradigms of Success and Failure

Overconfidently building increasingly longer bridges modeled on successful prior designs is a prescription for failure, as has been demonstrated and documented repeatedly over the past century and a half.

The Peril of Extrapolation. Overconfidently building increasingly longer bridges modeled on successful prior designs is a prescription for failure, as has been demonstrated and documented repeatedly over the past century and a half. The designers of the first Quebec Bridge, for example, were emboldened by the success of the Forth Bridge and set out to better it with a lighter and longer structure of its type.

The Quebec Bridge Disaster. Unfortunately, the Quebec collapsed while under construction, an event that gave the cantilever form upon which it was based a reputation from which it has yet to recover in the world of long-span bridge building. Though the Quebec Bridge was successfully redesigned and rebuilt and stands today as a symbol of Canada’s resolve, no cantilever bridge of greater span has been attempted since.

Tacoma Narrows Bridge. The Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the third longest suspension bridge when completed in 1940, proved to have too narrow and shallow a deck, which accounted for its collapse just months after it was opened to traffic. Such examples provide caveats against success-based extrapolation in design. Past success is no guarantee against future failure.

7. History's Echo: Learning from Colossal Failures

Such compelling evidence argues for a greater awareness among designers of the history of the technology within which they work, but such looking back is not generally in the nature of forward-looking engineers working on the cutting edge.

The Thirty-Year Cycle. The final chapter looks at the historical record of colossal failures, especially in the context of the space shuttle program and of long-span bridges. In the case of bridges, there is a striking temporal pattern of a major failure occurring approximately every thirty years since the middle of the nineteenth century and continuing through the millennium.

Root Cause: Success-Based Design. All of the half-dozen remarkable failures that occurred within this time span resulted from designs based on successful precedents rather than on a more fundamentally circumspect anticipation and obviation of failure. Such compelling evidence argues for a greater awareness among designers of the history of the technology within which they work, but such looking back is not generally in the nature of forward-looking engineers working on the cutting edge.

Anticipating Future Failures. It even suggests that a major bridge collapse can be expected to occur around the year 2030. Such a prediction gains credibility from the fact that bridge building in the twenty-first century continues to go forward in a way not unlike that which preceded the failures of the Quebec, Tacoma Narrows, and other overly daring bridges. Indeed, future failures can be anticipated and thereby avoided through an appreciation for the past, which reveals in case after case an incontrovertible if paradoxical relationship between success and failure in the design process generally.

Last updated:

FAQ

1. What is "Success through Failure: The Paradox of Design" by Henry Petroski about?

- Central Thesis: The book explores how failure is an essential and driving force in the process of engineering and design, arguing that successful designs are achieved by learning from and anticipating failures.

- Scope of Discussion: Petroski examines both tangible and intangible designs, from physical objects like bridges and buildings to systems, constitutions, and even sports strategies.

- Historical and Modern Examples: The book uses a wide range of case studies, including the evolution of presentation technology, the collapse of famous bridges, and the design of skyscrapers, to illustrate the interplay between success and failure.

- Paradox of Design: Petroski highlights the paradox that past successes can mask potential failures, and that overreliance on successful precedents often leads to unexpected disasters.

2. Why should I read "Success through Failure: The Paradox of Design" by Henry Petroski?

- Unique Perspective: The book offers a counterintuitive but compelling argument that failure, not success, is the true engine of innovation and improvement in engineering and design.

- Broad Relevance: While rooted in engineering, Petroski’s insights apply to a wide range of fields, including business, architecture, medicine, and public policy.

- Engaging Case Studies: The book is rich with real-world examples and historical anecdotes, making complex engineering concepts accessible and interesting to general readers.

- Practical Lessons: Readers gain a deeper appreciation for the importance of proactive failure analysis and the dangers of complacency in any creative or technical endeavor.

3. What are the key takeaways from "Success through Failure: The Paradox of Design"?

- Failure Drives Progress: The most significant improvements in design come from understanding and addressing the failures of previous designs.

- Success Can Breed Complacency: Relying too heavily on past successes can blind designers to new or hidden modes of failure, leading to catastrophic results.

- Proactive Failure Analysis: Good design is fundamentally about anticipating, identifying, and mitigating potential failures before they occur.

- Universal Application: The principles discussed apply not only to physical structures but also to systems, organizations, and even cultural practices.

4. How does Henry Petroski define "failure" and "success" in engineering design?

- Failure as Unmet Expectations: Petroski, referencing the American Society of Civil Engineers, defines failure as "an unacceptable difference between expected and observed performance."

- Success as Temporary: Success is not simply the absence of failure; it is often a temporary state that can mask underlying vulnerabilities.

- Failure as Opportunity: Failures, whether minor annoyances or catastrophic collapses, are seen as opportunities for learning, redesign, and innovation.

- Continuous Cycle: The relationship between success and failure is cyclical—today’s solutions often become tomorrow’s problems as expectations and contexts evolve.

5. What is the "paradox of design" discussed in "Success through Failure" by Henry Petroski?

- Success Conceals Failure: The paradox is that while success is desirable, it can hide latent flaws and encourage risky extrapolation beyond proven limits.

- Failure Enables Success: Conversely, failure is often the catalyst for meaningful improvement, as it exposes limitations and drives the search for better solutions.

- Historical Patterns: Petroski illustrates this paradox with examples like the repeated failures of long-span bridges, which often followed periods of unbroken success.

- Design Evolution: The paradox underscores that design is an ongoing process, with each iteration shaped by the lessons of both success and failure.

6. What are some of the most compelling case studies or examples in "Success through Failure" by Henry Petroski?

- Bridge Failures: The collapses of the Quebec Bridge and Tacoma Narrows Bridge are analyzed as classic cases where overconfidence in prior successes led to disaster.

- Skyscraper Design: The evolution of tall buildings, including the World Trade Center, demonstrates how new challenges and unforeseen failures shape architectural progress.

- Presentation Technology: The transition from magic lanterns to PowerPoint illustrates how each new technology solves some problems but introduces new limitations.

- Product Design: Everyday objects like luggage, Band-Aids, and medicine bottles are used to show how minor failures drive incremental improvements.

7. How does "Success through Failure" by Henry Petroski explain the role of proactive failure analysis in design?

- Anticipating Failure: Proactive failure analysis involves systematically identifying how a design might fail before it is built or used.

- Testing and Prototyping: The book emphasizes the importance of rigorous testing, prototyping, and even deliberately seeking out failure modes during development.

- Learning from History: Petroski advocates for studying past failures—both one’s own and others’—to inform safer and more robust designs.

- Continuous Improvement: Proactive failure analysis is presented as an ongoing process, essential for adapting to changing contexts and expectations.

8. What does Henry Petroski say about the dangers of emulating past successes in design?

- False Security: Emulating successful designs without understanding their limitations can lead to overconfidence and unexpected failures.

- Context Matters: Designs that work well in one context may fail in another due to differences in scale, environment, or use.

- Historical Patterns: The book documents a recurring pattern where a series of successes leads to a major failure, often as a new generation of designers loses touch with the reasons behind earlier caution.

- Need for Critical Analysis: Petroski urges designers to critically analyze both successes and failures, rather than blindly copying what worked before.

9. How does "Success through Failure" by Henry Petroski address the testing of small versus large designs?

- Small Things: Mass-produced small items can be tested statistically through sampling, allowing for the identification and correction of flaws before widespread failure.

- Large Structures: Unique, large-scale projects like bridges and skyscrapers cannot be fully tested until they are built, making proactive failure analysis and historical study even more critical.

- Proof Testing: While physical proof tests are sometimes used for large structures, they have limitations and cannot account for every possible failure mode.

- Role of Computer Models: The book discusses the increasing reliance on computer simulations, while cautioning that models are only as good as their assumptions and data.

10. What are some key concepts or methods introduced in "Success through Failure" by Henry Petroski?

- Proactive Failure Analysis: The systematic anticipation and mitigation of potential failures during the design process.

- Fast Failure and Prototyping: The value of rapid prototyping and embracing early, small failures to avoid larger, costlier ones later.

- Generational Forgetting: The idea that major failures often occur about every thirty years as institutional memory fades and new designers become complacent.

- Design as Hypothesis Testing: Viewing each design as a hypothesis about how something will perform, with real-world use serving as the ultimate test.

11. What are the broader implications of "Success through Failure" by Henry Petroski for fields beyond engineering?

- Universal Lessons: The book’s insights apply to any field involving design, innovation, or complex systems, including business, medicine, law, and public policy.

- Systemic Thinking: Petroski’s approach encourages thinking about the interconnectedness of components, users, and environments in any system.

- Cultural and Psychological Factors: The book addresses how ego, tradition, and organizational culture can influence design decisions and risk management.

- Policy and Regulation: Petroski discusses the limits of legislating safety and the importance of fostering a culture that values learning from failure.

12. What are the best quotes from "Success through Failure: The Paradox of Design" by Henry Petroski and what do they mean?

- "Failure is the key to design." This encapsulates the book’s central thesis that understanding and addressing failure is essential for successful innovation.

- "Past successes, no matter how numerous and universal, are no guarantee of future performance in a new context." Petroski warns against complacency and the dangers of assuming that what worked before will always work.

- "The most successful designs are based on the best and most complete assumptions about failure." This highlights the importance of thorough, proactive failure analysis in achieving robust and lasting solutions.

- "Emulating success risks failure; studying failure increases our chances of success." The book’s paradoxical message: true progress comes from a critical examination of what goes wrong, not just what goes right.

Review Summary

Success through Failure receives mixed reviews, with an average rating of 3.58/5. Readers appreciate Petroski's insights on learning from failure in engineering and design. Many find the historical examples and case studies enlightening, particularly regarding technological evolution. Some praise the book's message about embracing failure as a learning opportunity. However, critics note repetitive content, lack of images, and occasionally dull writing. Several reviewers recommend it for engineers and designers, while others find it less engaging for general readers.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.