Plot Summary

The Invisible Barrier Appears

A middle-aged woman, visiting a remote hunting lodge in the Austrian mountains, awakens to find herself cut off from the world by an invisible, impenetrable wall. Her hosts, Luise and Hugo, have vanished, and when she tries to reach the nearby village, she discovers that all life beyond the wall—humans and animals alike—has been petrified in death. The wall is smooth, cold, and utterly impassable, dividing her from the rest of humanity. The shock is profound, but the woman's practical instincts take over as she realizes she must survive alone, with only Hugo's dog, Lynx, for company. The world she knew is gone, replaced by a silent, isolated wilderness.

Alone in the Forest

The woman quickly understands that rescue is unlikely. She inventories the supplies left in the lodge—food, tools, weapons, and medicine—grateful for Hugo's anxious preparations. She begins to establish routines, organizing the house for safety and comfort, and starts to explore the boundaries of her new prison. The wall is a mystery she cannot solve, and the absence of any sign of life or rescue deepens her sense of abandonment. Fear and loneliness threaten to overwhelm her, but she clings to the tasks of daily living to keep despair at bay.

Animal Companions Gather

As days pass, the woman's world expands to include a cow she finds trapped by the wall, desperate for milking, and later a stray cat. She takes responsibility for these animals, naming the cow Bella and the cat simply "the cat." The animals' needs give her purpose and structure, and she comes to rely on their presence for emotional support. The relationships are not sentimentalized; they are rooted in mutual dependence and the daily labor of care. The woman's bond with Lynx, in particular, deepens into a true friendship, providing her with comfort and a sense of connection in her isolation.

Mapping the New World

Determined to understand her new environment, the woman methodically explores the area within the wall, marking its boundaries with sticks and branches. She discovers that the wall encloses a large but finite section of forest, meadows, and mountains. The process of mapping and naming places—fields, streams, the Alm (alpine pasture)—helps her impose order on chaos. She finds evidence of the catastrophe beyond the wall: dead villagers, frozen in their last moments, and lifeless animals. The horror of this discovery is tempered by the necessity of focusing on survival.

Survival and Routine

The woman's life settles into a rhythm dictated by the needs of her animals and the demands of the seasons. She learns to milk the cow, plant potatoes and beans, cut hay, and hunt deer for meat. The work is exhausting and often overwhelming, but it is also her salvation, keeping her mind occupied and her body strong. She struggles with practical challenges—blisters, toothaches, dwindling supplies—and adapts as best she can, using her limited knowledge and ingenuity. The routines of washing, cleaning, and maintaining the lodge become rituals that stave off the threat of losing her humanity.

The Weight of Memory

As the initial shock fades, the woman is increasingly troubled by memories of her past life: her children, now likely dead; her marriage; the trivialities and dissatisfactions of her former existence. She reflects on the limitations imposed on her as a woman, the burdens of care and expectation, and the ways in which she was never truly free. The wall becomes both a literal and metaphorical barrier, separating her from her old self and forcing her to confront who she is without society's roles. Writing a report of her experiences becomes a way to preserve her sanity and assert her identity.

The Seasons Turn

The passage of time is marked by the changing seasons, each bringing new challenges and tasks. Spring brings hope and renewal, summer is a time of abundance and hard labor, autumn is for harvest and preparation, and winter is a test of endurance. The woman becomes attuned to the rhythms of nature, learning to predict the weather, manage her resources, and accept the limits of her strength. The animals, too, are subject to these cycles—birth, illness, and death are ever-present realities. The seasons become both a comfort and a reminder of her vulnerability.

The Burden of Care

The woman's sense of duty to her animals is both a source of meaning and a heavy burden. She worries constantly about their well-being—whether she can protect them from illness, injury, or starvation. The arrival of kittens, the birth of a calf, and the needs of Lynx and Bella all demand her attention and energy. She is haunted by the knowledge that she cannot save them from every danger, and each loss is a fresh wound. Yet, caring for them is what keeps her from succumbing to despair; it is her way of resisting the meaninglessness of her situation.

The Cat's Arrival

The arrival of the cat, and later her kittens, adds a new dimension to the woman's life. The cat is independent, wary, and sometimes affectionate, a contrast to the loyal Lynx. The kittens bring joy but also anxiety, as the woman knows they are vulnerable to the dangers of the wild. The relationships among the animals—friendship, rivalry, and loss—mirror the complexities of human connection. The woman's interactions with the cat force her to confront her own need for affection and her fear of further loss.

The First Losses

The woman experiences her first major loss when one of the kittens, Pearl, is killed by a predator. Later, other animals die—Tiger, another cat; Bull, the calf; and most devastatingly, Lynx, her faithful dog. Each death is a blow, reminding her of the fragility of life and the inevitability of loss. Grief is compounded by guilt and helplessness, as she questions whether she could have done more to protect her companions. The deaths force her to confront the limits of her control and the reality of her solitude.

The Alpine Summer

Seeking better pasture for her animals, the woman moves to the Alm for the summer. The alpine meadow is beautiful and seemingly idyllic, and for a time she experiences a sense of peace and detachment from her troubles. The vastness of the sky and the rhythms of the stars bring her a new perspective, and she feels herself dissolving into the landscape, losing the boundaries of her old self. Yet, this tranquility is fragile, and the return to the valley in autumn brings a renewed sense of vulnerability and loss.

The Return and Change

Returning to the hunting lodge, the woman finds that nothing is as it was. The animals have changed, the routines are different, and she herself is altered by her experiences. The cat, who had stayed behind, is now more distant; Bull, the calf, is growing into a bull and becoming difficult to manage. The woman is forced to adapt once again, building new enclosures and finding new ways to cope with the demands of her environment. The sense of home is elusive, and she is increasingly aware of her own aging and physical limitations.

The Stranger's Violence

The fragile equilibrium of the woman's life is destroyed when a stranger appears in the alpine pasture. He kills Bull and Lynx with an ax before the woman can stop him. In a moment of self-defense and rage, she shoots and kills the man. The violence is senseless and inexplicable, and the woman is left to deal with the aftermath—burying Lynx, abandoning the Alm, and returning to the lodge with Bella. The event is a stark reminder that even in isolation, the threat of human violence persists, and it leaves her more alone than ever.

Grief and Endurance

The deaths of Lynx and Bull plunge the woman into deep grief, but she is forced to continue. She throws herself into work—repairing the road, harvesting crops, preparing for winter—as a way to cope with her pain. The routines of survival become both a refuge and a prison, and she struggles to find meaning in a world that seems increasingly empty. Yet, she endures, drawing strength from her memories, her animals, and the small pleasures of daily life.

The Meaning of Work

Over time, the woman comes to see work as the foundation of her existence. The endless cycle of tasks—planting, harvesting, feeding, cleaning—gives her life structure and purpose. She reflects on the difference between the artificial busyness of her former life and the meaningful labor of survival. The work is hard and often thankless, but it is also a form of resistance against despair and a way to assert her humanity in the face of annihilation.

The Vanishing Self

As the years pass, the woman feels her old self slipping away. She forgets her name, loses interest in her appearance, and becomes more like the animals she cares for—focused on the present, attuned to the rhythms of nature, and free from the expectations of society. The boundaries between human and animal, self and world, begin to blur. She finds a strange freedom in this dissolution, but also a sense of loss, as she realizes that everything she once valued is gone.

The Cycle Continues

Despite all the losses and hardships, life goes on. Bella may be pregnant again, and the cat, though old and changed, remains a companion. The woman continues to work, to care, and to hope, even as she acknowledges the futility and absurdity of her situation. The seasons turn, the wall remains, and the future is uncertain. Yet, the persistence of life—animal, plant, and human—offers a kind of redemption, however fragile.

Hope Beyond the Wall

In the end, the woman's report is both a testament to survival and a meditation on the meaning of existence. She does not expect to be rescued, nor does she believe that her story will be read. Yet, she writes as an act of defiance against oblivion, a way to assert her presence in a world that has forgotten her. The wall remains unexplained, a symbol of the barriers that separate us from each other and from ourselves. But as long as there is life, there is hope, however faint—a hope that something new will emerge from the ruins.

Characters

The Narrator (Unnamed Woman)

The narrator is a middle-aged Austrian woman whose life is upended by the sudden appearance of the wall. Initially practical and reserved, she is forced to become entirely self-reliant, drawing on reserves of strength and ingenuity she never knew she possessed. Her relationships with the animals in her care become central to her identity, providing both purpose and emotional connection. Psychologically, she is marked by a deep sense of responsibility, a tendency toward self-doubt, and a capacity for reflection that borders on the philosophical. Over time, her sense of self dissolves, and she becomes more attuned to the rhythms of nature and the needs of her animal companions. Her development is a journey from shock and fear to acceptance and a kind of hard-won wisdom.

Lynx (Dog)

Lynx is Hugo's hunting dog, a Bavarian bloodhound who becomes the narrator's closest friend and confidant. He is intelligent, sensitive to the woman's moods, and provides both practical assistance (protection, hunting) and emotional support. Lynx's loyalty is unwavering, and his presence is a bulwark against loneliness and despair. His death at the hands of the stranger is a devastating blow, symbolizing the loss of innocence and the fragility of the bonds that sustain the narrator.

Bella (Cow)

Bella is a cow the narrator finds and rescues early in her ordeal. She becomes a source of sustenance (milk, potential calves) and a symbol of the narrator's role as caretaker. Bella's needs structure the woman's days, and her presence is both a comfort and a burden. The birth of a calf is a moment of hope, while Bella's vulnerability is a constant source of anxiety. The relationship is one of mutual dependence, marked by tenderness and a recognition of the limits of understanding between species.

The Cat

The cat is a stray who joins the household, bringing with her a mix of affection, suspicion, and autonomy. She is less emotionally available than Lynx, but her presence is nonetheless important to the narrator's sense of connection. The cat's cycles of pregnancy, motherhood, and loss mirror the larger themes of care and grief. Her survival, despite illness and hardship, is a testament to resilience, and her relationship with the narrator is marked by a delicate balance of distance and intimacy.

Bull (Calf)

Bull is Bella's calf, born in the midst of the woman's isolation. He represents hope for the future and the possibility of renewal, but also the inevitability of loss. As he grows, he becomes more difficult to manage, and his eventual death at the hands of the stranger is a traumatic event that shatters the fragile stability of the narrator's world. Bull's life and death encapsulate the themes of vulnerability, care, and the limits of control.

Pearl (Kitten)

Pearl is one of the cat's kittens, distinguished by her white fur and gentle nature. Her brief life and violent death are a source of deep grief for the narrator, who is haunted by the image of her suffering. Pearl's fate underscores the precariousness of life in the wild and the pain of attachment in a world where loss is inevitable.

Tiger (Tomcat)

Tiger is another of the cat's offspring, a lively and affectionate tomcat who becomes the narrator's playmate and companion. His disappearance is another in a series of losses that erode the woman's sense of security and connection. Tiger's wildness and independence are both a source of joy and a reminder of the limits of domestication.

The Stranger

The stranger is the only other human the narrator encounters after the wall appears. His sudden, senseless violence—killing Bull and Lynx—shatters the fragile peace of the narrator's world. His motives are never explained, and his presence is a stark reminder of the dangers of human nature. The narrator's act of killing him in self-defense is both a necessity and a trauma, leaving her more isolated than ever.

Hugo

Hugo is Luise's husband and the owner of the hunting lodge. His obsession with preparedness and collecting supplies inadvertently saves the narrator's life. Though he never appears after the wall descends, his presence lingers in the form of the resources he left behind and the memories the narrator has of him.

Luise

Luise is the narrator's cousin and Hugo's wife. She is described as lively and impulsive, a contrast to the narrator's more reserved nature. Like Hugo, she disappears with the advent of the wall, and her absence is felt in the narrator's reflections on the past and the relationships she has lost.

Plot Devices

The Wall

The wall is the central plot device, both literal and symbolic. Its sudden appearance cuts the narrator off from the rest of humanity, forcing her into a state of radical isolation. The wall is never explained—its origin, purpose, and extent remain a mystery. It functions as a metaphor for the barriers that separate individuals from each other and from themselves, as well as for the existential condition of being alone in the universe. The wall's presence shapes every aspect of the narrative, from the practical challenges of survival to the psychological and philosophical questions the narrator confronts.

First-Person Report

The novel is structured as a first-person report, written by the narrator as a way to preserve her sanity and make sense of her experiences. The act of writing becomes both a coping mechanism and a means of asserting her identity in the face of erasure. The report is addressed to no one—she does not expect it to be read—but it serves as a testament to her existence and a record of her struggle.

Foreshadowing and Cyclical Time

The narrative is marked by a sense of inevitability and repetition. The cycles of the seasons, the recurring tasks of survival, and the repeated experiences of loss and grief create a sense of time as both circular and stagnant. Foreshadowing is used to build tension, as the narrator anticipates the dangers and losses that lie ahead. The structure reinforces the themes of endurance, futility, and the persistence of hope.

Symbolism of Animals

The animals in the novel are more than mere companions; they are symbols of different aspects of the narrator's psyche and of the human condition. Lynx represents loyalty and friendship, Bella embodies nurturing and dependence, the cat stands for independence and mystery, and the various offspring symbolize hope, vulnerability, and the inevitability of loss. The relationships among the animals and between the animals and the narrator are used to explore themes of care, responsibility, and the limits of understanding.

Minimalist, Practical Prose

The narrative style is plain, practical, and focused on the details of daily life. This minimalist approach mirrors the narrator's situation—stripped of distractions, she is forced to confront the essentials of existence. The prose is attentive to the rhythms of nature, the sensations of the body, and the minutiae of survival, creating a sense of immediacy and authenticity.

Analysis

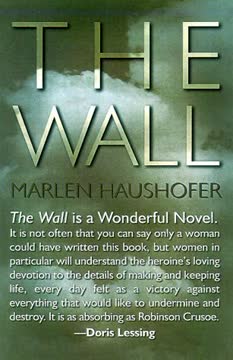

Marlen Haushofer's The Wall is a quietly devastating exploration of what it means to be utterly alone, stripped of the roles and routines that define us. Through the narrator's struggle to survive and care for her animal companions, the novel interrogates the foundations of identity, the burdens and consolations of responsibility, and the possibility of finding meaning in a world without witnesses. The wall itself is a potent symbol—of existential isolation, of the barriers between self and other, and of the arbitrary catastrophes that can upend our lives. The narrative's focus on the practicalities of survival grounds its philosophical inquiries in the realities of the body and the rhythms of nature. The novel is also a subtle critique of gender roles and the limitations imposed on women, suggesting that true freedom may only be possible in the absence of society's expectations. Ultimately, The Wall is a testament to endurance, to the fragile hope that persists even in the face of overwhelming loss, and to the possibility of finding grace in the act of caring for others, however small and vulnerable.

Last updated:

Review Summary

The Wall is a thought-provoking dystopian novel about a woman isolated by an invisible barrier in the Austrian Alps. Readers praise its atmospheric writing, philosophical depth, and exploration of survival, loneliness, and human-animal relationships. Many find it emotionally powerful and relevant to contemporary issues. Some criticize its slow pace and repetitive nature. The book's ambiguous ending and lack of explanation for the wall's existence leave room for various interpretations. Overall, it's considered a masterpiece of German literature, though its appeal may depend on individual taste.

Similar Books

Download PDF

Download EPUB

.epub digital book format is ideal for reading ebooks on phones, tablets, and e-readers.